Introduction

“We will do everything in our power to protect and defend every ally. And every square inch of NATO territory,” said then-NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg on 25 February 2022 at a press conference following the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine the day before. Since then, the phrase ‘Not an inch’ has become the slogan of the Atlantic Alliance’s leaders to show their determination to honour their commitment, as former US President Joe Biden declared during the extraordinary NATO summit on 24 March 2022 that “we will defend every inch of NATO territory. Not an inch will be given to aggression.” As this war has reignited fears of a larger conflict in Europe, it has led NATO to refocus on its primary mission: the defence of the territory of all its member states.

Since its creation in 1949, NATO has invoked Article 5 of the Washington Treaty only once, after the 11 September 2001 attacks on the United States by Al-Qaeda. Since then, there has been no need to invoke this article in response to a conventional armed attack. By increasing the number of joint military exercises, NATO seeks to improve the interoperability of allied forces and deter any potential attack against one of its members by demonstrating the credibility of each member’s commitment. During the Cold War, NATO was therefore able to demonstrate sufficient credibility in the face of the Soviet threat to avoid direct conflict. However, since the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Russian Federation has stepped up its negative actions against several NATO member countries, including disinformation campaigns, infrastructure sabotage and acts of vandalism aimed at increasing division within Western societies.

The year 2025 also marks a turning point in Russian provocations. Relations between the allies and the Trump administration have become strained, with the American president now believing that they must increase their military spending to ensure their own security and casting doubt on a potential American withdrawal from the old continent. Since this summer, Russia has escalated its provocations, repeatedly violating the airspace of several Member States (e.g., Poland, Estonia, Lithuania and Romania) during September.

These repeated violations show an escalation in Russian provocations against the credibility of the Alliance. Indeed, even before 2022, there had been limited incursions, but recent months have seen an intensification and a change in method (the use of drones). The Alliance must respond to these provocations and strengthen its deterrence if it wants to take control of the initiative and prevent Russia from maintaining its grip on the situation.

The Russian Army is Closing in on the Eastern Flank

It has been more than three and a half years since Russia launched its large-scale invasion of Ukraine, and although we are aware of the very high human cost on both sides, it remains difficult to establish this with any precision. Western intelligence estimates that Russia has suffered approximately 790,000 casualties,[1] making this the deadliest war for the Russian army since Soviet losses in the Second World War. At the same time, Russia’s territorial gains have remained relatively small, as since 2022, Russia has not advanced much and still controls ‘only’ 20% of Ukrainian territory (including Crimea). Russia’s advances in the Donbass region of Ukraine since 2023 have certainly included numerous localities, but they remain at a tactical level and no major breakthroughs have allowed Russia to make strategic gains. However, it should be noted that Russia seems to be adapting to the war effort in Ukraine and is now in a position to cause concern to the various NATO countries by being active across the Alliance’s entire eastern flank.

On the one hand, the start of the 2025 academic year is marked by Russia’s major biennial military exercise, Zapad. The last Russian military exercise in the west took place in 2021, a few months before the invasion of Ukraine. The exercise planned for 2023 did not ultimately take place, and some Westerners, such as the British Ministry of Defence, believed that this was due to a lack of troops and military equipment. From 12 to 15 September 2025, Zapad-2025 was therefore organised in Russia and Belarus. Russian President Vladimir Putin explained that this exercise is taking place on 41 different training grounds, involving around 100,000 soldiers. This exercise, which is also a show of force to NATO members, has raised fears among many allied countries close to the Russian border, as in 2021 the troops participating in the exercise remained near the Ukrainian border and took part in operations. Several allies therefore took part in various military exercises, such as the ‘Tarassis 25’ exercise, which brings together a dozen northern European countries and NATO members, the annual Lithuanian national defence exercise ‘Thunder Strike’ and the Polish exercise ‘Iron Defender-25’, involving around 30,000 soldiers.

On the other hand, NATO’s north-eastern flank is also experiencing renewed activity. On 4 April 2023, Finland, which had remained outside the transatlantic alliance since its creation in 1949, joined the military alliance in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine a year earlier. Since joining, the alliance has been working closely with Finnish officials. A few days before the Hague summit in the summer of 2025, Finland announced its wish to host a group of advanced ground forces on its soil in the form of a brigade (5,000 soldiers) from around six countries, including Sweden, the latest state to join the alliance. On 3 October 2025, Finnish Defence Minister Antti Häkkänen inaugurated NATO’s Joint Land Command (MCLCC) in Mikkeli, illustrating Helsinki’s full integration into the alliance. However, on the other side of the border, in Russian Karelia, there has been a military build-up for several months. The Russian armed forces have redeployed resources to military bases abandoned since the end of the Cold War and have also announced a new military base to serve as an operational platform for the Baltic and Arctic theatres. The Finnish government has announced that it is closely monitoring the situation, fearing an increase in tensions in the region.

While the first two years of the war in Ukraine forced Moscow to mobilise a large part of its forces in the theatre of operations, the Russian army is now strengthening its presence on the borders of Member States, raising fears of provocations against them. However, after military exercises and infrastructure construction, it appears that Russia has decided to move forward with its attempts to assess the strength of NATO’s defences.

Increased Violations of Allied Territory

September 2025 saw a significant increase in Russian actions against NATO allies. On the one hand, this increase in actions is causing great concern among allies in Europe. On the other hand, the US president is becoming increasingly impatient with Russia’s lack of commitment to peace talks, or at least a ceasefire, in Ukraine.

On the night of 9 to 10 September, Polish airspace was on alert after identifying a massive incursion of Russian drones (between 19 and 23 drones) coming from Belarus at the same time as an attack on Ukraine by Russia. This incursion, too large to be a simple error or system failure, prompted a response from Poland and its allies. Several fighter and reconnaissance aircraft took off,[2] and ground-based radars and air defence systems were put on high alert to monitor the drones’ route and shoot them down if necessary. Poland also closed its eastern airspace on the border with Ukraine and Belarus, as well as several of its airports. Following this event, Warsaw invoked Article 4 to meet with its NATO allies, claiming that Poland’s security was under threat.

Just a few days after this incursion (19 September 2025), a new alert was issued, this time in Estonia. Tallinn reported the violation of its airspace by three Russian fighter jets (MiG-31) near the island of Vaindloo in the Gulf of Finland. This violation, which lasted about 12 minutes, was considered very serious due to several factors: transponders turned off, no flight plans and no radio contact with Estonian air traffic control. Although this incursion was not the first of the year, it was the longest. As with Poland a few days earlier, Estonia invoked Article 4 to bring the Allies together and discuss the threat to its security.

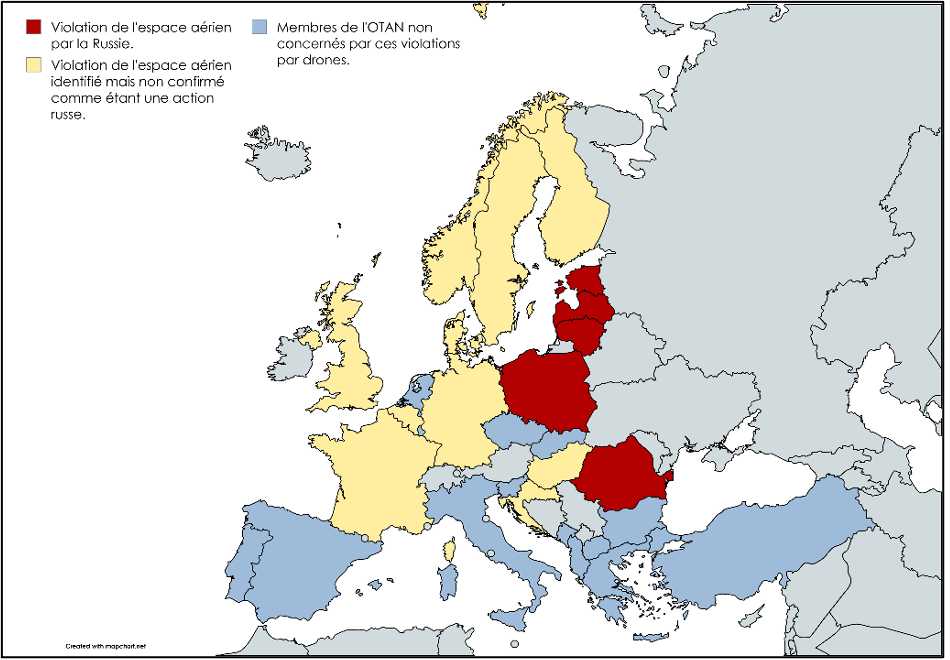

Finally, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there has been an increase in violations of NATO members’ airspace (see Figure 1). The most notable incidents occurred in Denmark, where for several nights, multiple unidentified drones flew over airports (Copenhagen, Billund, Aalborg), but also and above all military bases in Skrydstrup and Karup. These flyovers prompted the Danish government to close its airspace and airports for several hours each time an alert was issued. Without directly accusing Russia, Copenhagen denounced a possible ‘hybrid attack’ on its territory. In the same region, the Karlskrona archipelago in Sweden, where a naval base is located, was also flown over by drones similar to those identified in Denmark. Drones have also been identified in other countries such as Belgium, Germany and France. Although it is not possible to identify these drones as part of operations carried out by Russia, some doubts may be raised due to the sensitive locations near which these flights were detected. For example, in France, an alert was issued over the Mourmelon-le-Grand military base at the end of September. This military base, home to the 501st Tank Regiment, was responsible for training the Ukrainian Anne de Kyiv Brigade in 2024.

Figure 1 – Map showing NATO member countries in Europe that have publicly reported violations of their airspace by drones since 24 February 2022.

Figure 1 – Map showing NATO member countries in Europe that have publicly reported violations of their airspace by drones since 24 February 2022.

Russia’s multiple violations of NATO countries’ airspace demonstrate a clear intention on Moscow’s part. From a military perspective, these incursions can be seen as testing allied defences and their responsiveness in the event of an attack or direct threat. From a political perspective, these incursions serve to gauge the level of support among NATO members, at a time when the US administration continues to criticize its European allies. Moscow also appears to be testing the allies’ determination to defend all of their territories and to enforce the ‘not an inch’ policy.

The Allies’ Firm Response

Faced with increasing Russian provocations, NATO members responded with strong statements and concrete actions.

NATO allies took turns speaking before the UN Security Council in New York in September to warn of the seriousness of the situation. At an emergency meeting on 12 September 2025, the Polish delegation reported some 20 incursions, some of which caused minor material damage. Poland described this action as a deliberate provocation. On 22 September, the Estonian Foreign Minister in turn denounced a dangerous escalation by Russia after the incursion of MiG-31s into its airspace. During the same session, Tallinn received the support of the United States, which reiterated that any violation of an ally’s airspace was a threat to collective security, calling on Moscow to exercise restraint. The French delegation also denounced a pattern of repeated provocations against NATO’s eastern member states. It reiterated France’s unwavering solidarity with its Baltic and Polish partners. Finally, a Nordic statement (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden) was made on the same day by the Swedish Minister for Foreign Affairs condemning the violation of Estonian airspace. These interventions were followed on 23 September by a statement from the North Atlantic Council reaffirming NATO’s collective determination to defend the territorial integrity of its members in a coordinated manner.

Between the statements in New York and that of NATO as a whole, the allies displayed unwavering unity, which was also, and above all, reflected in concrete actions. On 12 September, NATO announced the launch of Operation Eastern Sentry, which aims to strengthen the Alliance’s defence posture on its eastern flank. The operation includes the mobilisation of Allied forces with additional combat aircraft and air defence systems deployed. As part of this operation, several allied countries quickly deployed resources to Poland. The United Kingdom deployed RAF Typhoons and France deployed Rafale fighters directly to Poland. The French announcement was the subject of particular attention, as it was possible to identify the origin of these fighters. The three fighter jets deployed to Poland are part of the 2/4 La Fayette Fighter Squadron, based at Saint-Dizier Robinson Air Base 113 (BA 113), which is home to part of the French Strategic Air Force (FAS) responsible for nuclear deterrence. The deployment of fighter jets from the nuclear deterrent forces sends a strong strategic message to Russia about France’s determination to defend its allies in Europe. Other allies such as Denmark (F-16) and Germany (Eurofighter Typhoon) have also sent resources to reinforce air cover on NATO’s eastern flank. Finally, several NATO and EU members have decided to create a new initiative to establish a ‘wall of drones’ along the eastern flank called Eastern Flank Watch.[3] The aim of this initiative is to improve detection and response to Russian incursions into allied airspace.

NATO members responded unanimously to condemn Russia’s actions on the alliance’s eastern flank. Beyond mere words, this response has taken the form of concrete action in the form of operational reinforcement through the launch of Operation Eastern Sentry. For its part, Canada has issued numerous political statements reiterating its full support for its allies, but no concrete action has been taken in response, making Ottawa a peripheral player in the crisis.

However, despite this show of unity among the Allies, there is now a major issue regarding American support, which remains a thorn in the side of the Alliance. Indeed, the Allies remain primarily dependent on the United States for military support. European allies are still unable to match Washington in terms of logistical, industrial and material capabilities, whether in terms of supply chain, strategic transport or air and maritime support. The return of US President Donald Trump poses a serious challenge to the Alliance, calling into question the American commitment, which could eventually lead to a reconfiguration of NATO. So despite the images of unity, NATO and its deterrence capability in the face of the Russian threat remain dependent on the decisions of the US government, and it is not certain that the Allies would be able to ensure their security if the US commitment were to be reduced.

The Kremlin’s Military and Economic Difficulties

Moscow’s multiple provocations in September conceal a military and economic situation that is more difficult than the Kremlin would have us believe.

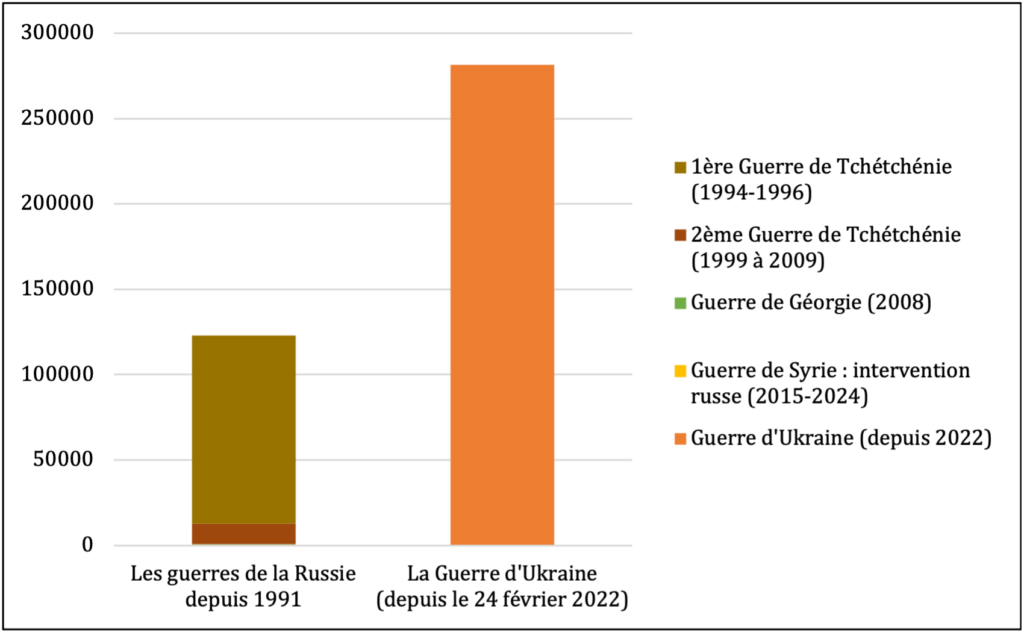

On the military front, Russian forces in Ukraine are struggling to make significant advances. Russian losses continue to mount, with an estimated 59 casualties per square kilometre conquered in 2024. In September 2025, average Russian losses were estimated at around 950 soldiers per day, with approximately 332,000 casualties since the beginning of 2025, according to the British Ministry of Defence. The years 2024 and 2025 are the deadliest for the Russian army since the invasion began, representing no less than double the Russian losses in its other wars since 1991 (see Figure 2), with average daily losses of between 1,000 and 1,500 soldiers, compared to 400 to 530 in 2022. By way of comparison, the Soviet Union’s war in Afghanistan, which is particularly unpopular in the memories of Russians, caused the loss of ‘only’ around 13,833 soldiers between 1979 and 1989. The Russian regime has not experienced a war with such high mortality since 1945, so much so that the government decided to stop publishing demographic data through its agency Rosstat in the summer of 2025. This is a way of hiding the level of losses. In addition to these human losses, there have also been significant material losses in Ukraine, forcing Moscow to mobilise a large part of its industrial capacity for military production.

Figure 2 – Graph comparing estimated Russian losses in Ukraine since 2022 with other conflicts in which Russia has been involved since 1991.[4]

Figure 2 – Graph comparing estimated Russian losses in Ukraine since 2022 with other conflicts in which Russia has been involved since 1991.[4]

Economically speaking, Russia has seen its primary asset for financing its war in Ukraine (oil and gas) severely damaged by Kyiv’s deep strikes against its energy infrastructure. It was not until September 2025 that Ukraine was able to intensify its attacks on Russian oil facilities in various cities such as Volgograd, Ryazan and Saratov. These strikes led to temporary closures and reduced production. In August 2025, there were around 20 strikes, double the number in September 2025. Although the Russian government does not publish any data on its oil production situation, certain indicators suggest that a fuel distribution crisis is emerging in Russia. In September 2025, internet searches on Yandex (the Russian equivalent of Google) for oil in the country peaked at 114,000, compared to 79,000 two years earlier. In addition to this damage to infrastructure, Russia is also finding it difficult to find energy buyers, as European Union member states have begun reducing their imports of Russian gas, which are expected to be zero by 2027.

As it intensifies its war in Ukraine and takes increasingly aggressive action against NATO members, Russia faces significant military and economic difficulties. The projection of an image of strength and determination hides a situation that is more critical than the Kremlin is willing to admit, mocked by the US President who describes the Russian Federation as a ‘paper tiger’.

Political Considerations for Canada

The growing tensions are still far from Canadian territory, but they have serious consequences for the collective defence of NATO, of which Canada is a member. It is important for the current government to continue to monitor the situation and maintain its message of unwavering support for its European allies.

What should Canada take away from these Russian incursions into NATO airspace?

Political considerations to keep in mind:

Canada’s presence in Latvia

Canada plays a leading role in NATO’s defence system in Europe, particularly in the Baltic region, where it is the framework nation for the multinational brigade in Latvia as part of Operation Reassurance. This mission, launched in 2014, is the Canadian Armed Forces’ largest overseas military commitment. In August 2025, the Carney government extended the operation until 2029, signalling Canada’s determination to contribute to collective security. In 2026, brigade-level capabilities are expected to be fully achieved with approximately 2,200 Canadian soldiers present. However, this extension means that Ottawa will have to make a significant military effort to ensure its mission, neglecting other potential theatres of operation such as the Arctic.

The vulnerability of Canada’s Arctic defence

Despite its active role in Europe, Canada remains militarily vulnerable in the Arctic, a region that is strategic for Canada’s raw materials and threatened by several powers, notably Russia. Canada’s defence capabilities in the North are still limited, as indicated in a 2023 Senate report, with an insufficient number of icebreakers and underdeveloped surveillance infrastructure. The Canadian Armed Forces are working to strengthen their presence in this region with the aim of deploying an almost permanent presence.

Complex relations with the US administration

Since the start of Donald Trump’s new term in office, relations between Canada and the United States have been marked by tensions due to protectionist trade policies and differences over defence priorities. This tension is undermining North American coordination within NATO. Canada is therefore attempting to manoeuvre between improving its bilateral relations with Washington on trade issues and strengthening cooperation in the area of collective defence, both within NATO and through NORAD.

Recommendations for the Canadian Government

1) Support a firm allied response to incursions

The Government of Canada should publicly support the position of several European allies who are calling for the shooting down of any Russian aircraft (drone or fighter jet) that violates NATO airspace. A public statement by the Prime Minister could carry significant weight in Canada’s position within NATO. It would also be possible to deploy Royal Canadian Air Force aircraft on the eastern flank, particularly for maritime reconnaissance with CP-140 Aurora aircraft, thereby strengthening Canada’s presence in collective defence. This support would send a clear signal about the Alliance’s determination, deterring Moscow from further testing the limits of collective defence. A firm, coordinated position would strengthen the credibility of the deterrent posture and potentially reduce the risk of further provocations. Indeed, there could be fears that if the allies do not respond sufficiently, Canadian forces deployed in Latvia as part of Operation Reassurance could be targeted by drones.

2) Strengthen the protection of territory and critical infrastructure

Canada should increase technical and military cooperation with its allies and Ukraine to improve the defence of sensitive infrastructure against drone threats. This enhanced cooperation would enable the joint development of anti-drone capabilities and the training of personnel for this purpose. This cooperation would therefore improve internal defence for military infrastructure (naval, air and land bases) as well as all sensitive civilian infrastructure (airports, ports, power plants, rail logistics, etc.). The alliance’s current air defence capabilities have proven difficult to intercept Russian Geran drones (the Russian version of the Iranian Shahed), but above all, they are very costly. Following the incursions into Poland, Ukraine offered to help train Polish soldiers to shoot down these threats. Canada could therefore consider establishing training for members of the Canadian Armed Forces with Ukrainian partners in particular.

3) Intensify Arctic cooperation with Nordic allies

Canada could also strengthen its military and strategic cooperation in the Arctic with the Nordic NATO member countries (Norway, Denmark, Finland and Sweden) in order to better anticipate and counter potential Russian threats (air and/or naval). Agreements already exist with Finland in particular, but this cooperation could include increased coordination of air and maritime patrols or even consideration of a drone surveillance programme for the Arctic Flank Watch region, similar to the Eastern Flank Watch mentioned above, which would aim to establish an intensive joint surveillance system. The signing of the ICE Pact between Canada, Finland and the United States illustrates this strengthening of cooperation in the Arctic with the joint production of icebreakers.

[1] This number includes both wounder and killed.

[2] From Poland, the Netherlands, and Italy.

[3] Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Finland.

[4] Sources: 1st Chechen War, 2nd Chechen War, Russo-Georgian War, Russian Intervention in Syria, Russo-Ukrainian War.

Comments are closed.