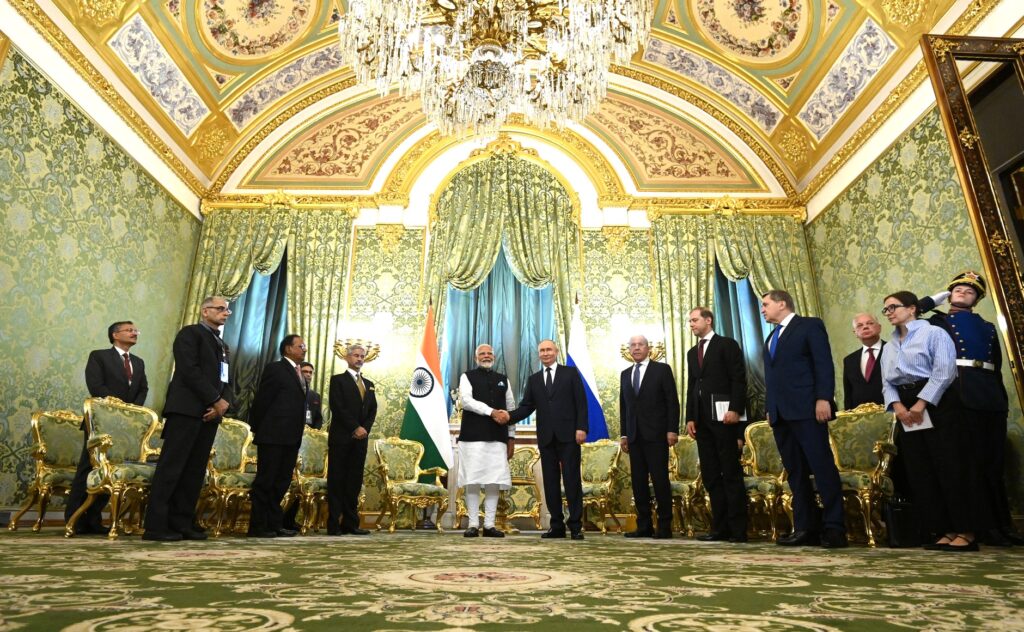

On August 7, India’s National Security Advisor, Ajit Doval, confirmed that Russian President Vladimir Putin would make an official visit to New Delhi at the end of 2025, amid growing tensions between India and the United States. This will be his first visit to India since the start of the war in Ukraine. The announcement followed a diplomatic sequence that began in July 2024, when Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi travelled to Moscow—his first visit since 2019 (while he had hosted Vladimir Putin to New Delhi in 2021). This trip, coming just a month after his re-election to a third term, sparked sharp international criticism, particularly because of its timing: it coincided with a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) summit and came shortly after Russia bombed a children’s hospital in Ukraine. In the United States, Deputy Secretary of State for South Asia, Donald Lu, expressed “disappointment about the symbolism and timing of Indian Prime Minister Modi’s trip to Moscow. We are having those tough discussions with our Indian friends.”

In this context, and with the presidential visit scheduled for the end of 2025 approaching, this article aims to assess the depth of the partnership between India and Russia, more than three years after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. It will also examine the debates this relationship has generated in New Delhi, as well as the prospects opened up by Donald Trump’s return to the White House. While the partnership rests on solid historical foundations and converging strategic interests, it is undeniable that the relationship has been—and continues to be—tested by several regional and global factors. Today, however, the partnership appears compatible with India’s vision of a multipolar world, in which it seeks to maximize its strategic autonomy, something that Russia continues to make possible.

A Historic Partnership Built on Strategic Convergences

In March 2025, Indian Minister of External Affairs Subrahmanyam Jaishankar reiterated that “India immensely values its relation with Russia,” a partnership based, in his words, on a “long tradition of trust and mutual respect.” A few months earlier, during a visit to Moscow, Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh had used a phrase widely reported in the Indian media: “Friendship between our countries is higher than the highest mountain and deeper than the deepest ocean.” The metaphor was borrowed from former Pakistani Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani, who once used it to describe ties between China and Pakistan.

This “special and privileged strategic partnership” rests above all on deep historical foundations, especially when compared with more recent bilateral partnerships. Past generations of Indian political and diplomatic elites remember Russia as a loyal ally, often described in interviews as having “stood by India when no one else did.” This perception is particularly pronounced in relation to the 1971 Bangladesh War of Independence. During that conflict, the United States, aligned with Pakistan, deployed Task Force 74 in the Bay of Bengal, while the Soviet Union firmly supported India. It was also in this context that the 1971 Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation was signed, a notable strategic moment in Indian history, marking, for the first time since independence, a relative departure from Nehru’s policy of non-alignment. More broadly, the Soviet Union backed India in international institutions, in a context of Indian territorial unification and recurring tensions with Pakistan and China. Between 1957 and 1971 alone, the Soviet partner cast six vetoes in the UN Security Council in favour of New Delhi.

Beyond these historical ties, Russia continues to enjoy a relatively positive image among Indian public opinion. According to a Pew Research Center survey published in 2023, 57 % of respondents expressed a favourable view of Russia, and 59 % said they had confidence in Vladimir Putin. On contemporary issues, the perception is even more favourable, with 71 % of respondents considering it more important to maintain access to Russian oil and gas than to adopt a tougher stance on the war in Ukraine.

At the strategic and economic level, convergences remain, though they warrant nuance. To begin with, both states share a common ambition: to enhance regional connectivity in order to expand their trade relations. In this regard, the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) represents a central pillar. In 2024, the signing of a ten-year contract for the development of the Iran’s Chabahar port, combined with a doubling of trade between India and Russia along the corridor, marked a significant step forward for the project—despite persistent challenges, reinforced in particular by the new Trump administration’s announcement of its intent to roll back the sanctions waiver that India had thus far enjoyed at Chabahar. In addition, New Delhi and Moscow are considering deeper cooperation in the Arctic region, especially in the exploitation of natural resources, an objective reaffirmed by both leaders at the July 2024 summit. However, when it comes to energy trade—oil and gas—an issue at the heart of debates since the start of the war in Ukraine, many experts view it more as opportunism than “a step forward in the relationship.”

At the July summit, the two countries highlighted two additional areas in which they intend to strengthen cooperation. The first concerns civil nuclear energy: to date, Russia remains the only country to have successfully built nuclear power plants at Kudankulam, just before the start of the war, and it plans to pursue similar projects. The second area is space cooperation, which dates back to the 1970s with the launch of India’s first satellite, Aryabhata, by a Soviet Cosmos-3M rocket from the Kapustin Yar base. In July 2024, Moscow and New Delhi reaffirmed their commitment to strengthening ties between the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) and the Russian space agency Roscosmos.

Finally, and this aspect will be explored in greater detail later, the India-Russia strategic partnership still relies heavily on India’s imports of Russian weaponry and on the local co-production of platforms and ammunition. While Russia remained India’s leading arms supplier between 2020 and 2024, accounting for 36 % of the country’s imports, this share has declined significantly compared with earlier periods: 55 % between 2015 and 2019, and 72 % between 2010 and 2014. This trend reflects India’s diversification of its arms import sources, turning notably to France (33 % of Indian imports between 2020 and 2024), Israel (13 %), and the United States.

Thus, despite recent developments, several strategic and political convergences persist, which explains why the partnership with Russia has been little questioned in India. Nevertheless, it is undeniable that the war in Ukraine has created difficulties for the Russia-India relationship.

A Relationship Put to the Test Since 2022: Reading Strategic Signals and Implications for Arms

New Delhi’s stance on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, by choosing not to condemn Moscow explicitly, has been closely scrutinized since February 2022. Despite this, India’s official rhetoric has changed very little over the three years of war. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has spoken minimally on the subject, merely noting that “today is not an era of war” and, more recently, during his visit to Ukraine, stating that India had “chosen the side of peace”. One of the most frequently cited arguments by the Indian Minister of External Affairs, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, in response to criticism, is the geographical distance of the conflict: the war is perceived as European and would only have become global because of the sanctions. By extension, it holds little strategic importance for countries like India; thus, as Jaishankar put it, “Europe has to grow out of the mindset that Europe’s problems are the world’s problems, but the world’s problems are not Europe’s problems.”

The few critical voices at the start of the war have mostly fallen in line, such as parliamentarian and former Minister of State for External Affairs Shashi Tharoor, who had criticized India’s lack of condemnation in 2022. At the 2025 Raisina Dialogue, he acknowledged that India has a Prime Minister who “ can hug both the president of Ukraine and the president in Moscow two weeks apart and be accepted in both places.” More broadly, the Raisina Dialogue, the annual multilateral conference held in New Delhi under the aegis of the Indian government, which had been criticized in 2023 for giving a platform to Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, reaffirmed itself this year as a showcase of India’s multipolar approach, sometimes described as a “fence-sitting” stance. With six panels addressing the issue of Ukraine and, more broadly, the future of Europe, the 2025 Raisina Dialogue was perceived by many observers as overly focused on the European continent.

Another issue that could have seriously strained relations between Moscow and New Delhi, but which ultimately had “surprisingly” few diplomatic repercussions, concerns the presence of around one hundred Indian nationals fighting on the Russian front (of whom 12 are reported to have died to date). Many had gone for economic reasons, attracted by the promise of Russian naturalization after six months of service. In reality, their passports were confiscated upon arrival, and they were sent directly to the front lines. Subrahmanyam Jaishankar stated in front of the Indian Parliament that this was a priority issue that Prime Minister Narendra Modi had raised with Vladimir Putin in July 2024. Following a few reports in the Indian media, negotiations quickly led to the repatriation of 97 individuals, while 16 were declared “missing” by the Russian military.

Thus, the war in Ukraine does not appear to have significantly altered India’s rhetoric toward Russia; however, the bilateral relationship has indeed been tested by the conflict for several reasons: the potential costs, particularly in the long term, associated with strategic signals perceived as favourable to Moscow, as well as the difficulties encountered in arms deliveries.

Debates on Strategic Signals and Their Costs

The Prime Minister’s visit to Moscow in 2024 elicited mixed reactions in India. Some praised it as a timely demonstration of India’s strategic autonomy—an autonomy that would “lose its significance if not upheld during the times of conflict.” Others, however, highlighted the limited concrete gains achieved during the visit, while questioning the rationale behind this diplomatic signal: it is unclear that “the reputational costs of Modi’s trip were outweighed by the supposed benefits of showcasing New Delhi’s ability to make independent foreign policy choices.”

In contrast, Narendra Modi’s visit to Kyiv in August 2024, the first by an Indian Prime Minister to Ukraine since 1991, provoked more critical reactions in India: “Zelensky’s statements on Modi’s visit were most improper. […] This is arrogant politics and an attempt to dictate India’s course of action.” Another comment noted: “Modi’s visit to Kyiv was not just ill-timed; India got an earful from Zelensky.” Nevertheless, the trip also helped to offset the strategic signal sent by the Moscow visit the previous month. Perceived as largely symbolic, the visit aimed to demonstrate India’s willingness to maintain the delicate diplomatic line it has upheld since 2022.

Beyond the issues of strategic communication, the war in Ukraine has highlighted the long-term risks of weakening some of India’s partnerships due to its ambiguous stance. While this posture has not provoked immediate or medium-term diplomatic or official reactions, it remains a source of concern, as one interlocutor confided in an interview: it carries the risk of “winning a battle but losing the war.” This concern is compounded by the perception of a “declining utility” of the partnership with Moscow. Rajesh Rajagopalan, professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University, points out that “far from driving a wedge between Russia and China, India’s Russia gambit is now possibly threatening to drive one between New Delhi and its Indo-Pacific partners.” Beyond the level of consideration expected from Western partners, the conflict in Ukraine has also underscored the lack of “drivers” or solid foundations in the relationship between India and Russia. According to analyst Happymon Jacob, it now appears to be “highly symbolic, but somewhat lacking in substance,” gradually evolving toward a more “transactional” logic.

However, despite these warnings urging caution against overestimating the depth of the partnership and highlighting the potential cost of these strategic signals to India’s other partners, particularly Western ones, New Delhi appears inclined toward deepening this relationship. Moreover, the new Trump administration has reshuffled the cards by adopting a stance on the war in Ukraine that contrasts sharply with that of the previous administration. Indeed, President Trump and his team place the responsibility for the war on Ukraine, thereby creating transatlantic divisions over the approach toward Russia. These divisions are likely to influence India’s strategic calculations; India’s position could become much easier to maintain over the next four years, and the “risks” associated with deepening the partnership could be considerably lower.

Concerns about Arms Deliveries

The trend toward diversification of India’s military procurement, particularly its gradual distancing from Russia, is a long-term phenomenon that began well before the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. Some analysts had already suggested that India would avoid signing new “mega-contracts” in the future, even as the question of acquiring a fifth-generation fighter jet arises, between the Russian Sukhoi-57, highlighted at the Aero India 2025 airshow, and the American F-35, following Donald Trump’s (perhaps symbolic) offer. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, however, has accelerated this diversification trend and raised new concerns within India’s defence community, based on lessons learned from the battlefield. Concerns have particularly focused on the ability of Russian weapons platforms to meet the demands of modern warfare, even though, as elsewhere in the world, analysts are drawing lessons from the war and are reassured by the fact that this equipment is being tested in combat.

In the shorter term, Indian concerns have focused on delivery delays and the indirect effects of Western sanctions imposed on Russia. The case of the INS Chakra III is particularly illustrative: this Akula-class nuclear attack submarine, for which the contract was signed in 2019 with an initial delivery scheduled for 2025, is now expected to reach India only in 2028. This delay could have significant consequences for India’s power-projection capabilities, especially in the context of a substantial increase in Chinese naval presence in the Indian Ocean, even though the Indian Navy is also diversifying its sources by acquiring additional Scorpène and German submarines. Other delays have reinforced these concerns. The two Talwar-class frigates, contracted in 2018, were originally due for delivery in 2022-2023; however, the first, INS Tushil, was commissioned only in December 2024, and the second, INS Tamal, not until July 1st, 2025. Finally, it is primarily the fourth and fifth S-400 systems that are causing worry: their delivery has been postponed twice and is now expected to take place in 2026, a “major delay” that was discussed during the Indian Defence Minister’s visit to Moscow in December 2024.

These systems are particularly essential in the defence of India’s land borders with its Chinese and Pakistani neighbours. Their effectiveness was in fact tested during the recent Indo-Pakistani conflict in May 2025, as were the jointly manufactured BrahMos missiles. Beyond these large contracts, difficulties and delays have also been observed in the delivery of spare parts, which have been identified as a “major problem” for India.

These concerns, while important, must nonetheless be put into perspective given the many other contracts that involve production on Indian soil. The acquisition of 12 additional Su-30MKs at the end of 2024, as part of the “Super Sukhoi” modernization project, for example, allows India to produce the aircraft locally, with 62.6 % of the components sourced from Indian industry, via Hindustan Aeronautics Limited. Similarly, a contract signed in 2019 provides for the local production of 464 T-90S tanks from blueprints and parts supplied by Russia, accompanied by the signing of an “Acceptance of Necessity” to acquire 1,350 additional engines intended for the modernization of existing armoured vehicles. In the same vein, the construction of two additional Talwar-class frigates (in addition to those imported from Russia, whose delivery was delayed) was launched at the Goa shipyard, with the INS Triput launched in July 2024.

These acquisitions are ideal for India, which is seeking to transition toward a more autonomous defence industry while maintaining its operational capabilities; the local production model with partial technology transfer thus enabling it to maximize its strategic autonomy. It is nevertheless noteworthy that, in the framework of Operation Sindoor, launched by India in response to the Pahalgam attack in May 2025, no Russian-origin platforms, particularly the Sukhois and MiGs, were deployed to carry out strikes—only to conduct combat air patrols. The question remains as to whether this was a deliberate strategic choice or an operational constraint.

Difficulties Arising from New Regional and International Dynamics

The India-Russia-China Strategic Triangle

A third factor weakening the Indo-Russian partnership is undoubtedly the strategic rapprochement between Beijing and Moscow, which constitutes a major irritant for New Delhi. This “no-limits friendship,” proclaimed in 2022, was highlighted by NATO members at the July 2024 summit (which coincided with Narendra Modi’s visit to Russia), whose communiqué described China as a “decisive enabler” of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Historically, Russia has remained neutral on Sino-Indian disputes, with Moscow consistently reiterating that border tensions were a “bilateral issue.” However, within strategic circles in New Delhi, there is growing concern about China’s ability to influence certain Russian decisions, which could block or slow down projects deemed too favourable to Indian strategic interests. This concern is all the greater given that China has been identified as India’s main long-term security challenge. This dynamic has even led some Indian military officials to adopt an unusually critical tone, such as former Chief of Army Staff General Manoj Mukund Naravane, who published an op-ed arguing for a less conciliatory stance toward Russia because of its rapprochement with China.

In this context, the recent and relative improvement in Sino-Indian relations, most notably illustrated by the meeting between Narendra Modi and Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the BRICS summit in Kazan in the fall of 2024, was welcomed by Moscow. This détente could, in the short term, help reduce certain tensions. Still, in the longer term, the evolution of this “strategic triangle” will remain a decisive factor in the depth of the Indo-Russian partnership. This India-China-Russia triangle is sometimes presented as “the most important foreign policy challenge in the coming years.” For India, this challenge lies in avoiding the strengthening of the China-Russia axis, out of fear that total isolation might push Russia into China’s arms and turn it into a “client state” of that adversary. In the longer run, New Delhi anticipates that once the war ends, Moscow will seek to rebalance its partnerships so as not to remain dependent on Beijing. This strategic triangle is also rooted in broader groupings and dynamics, whether within the Shanghai Cooperation Organization or BRICS+, as well as in the competing claims of China and India to leadership of the “Global South,” each with a very specific vision of what that entails.

Thus, within this strategic triangle, India may seek to exploit weaknesses in the Sino-Russian relationship, something encouraged by specific strategic signals Russia has directed toward India. As analyst Happymon Jacob explains, “from the Indian perspective, the best-case scenario would be to drive a wedge between Russian and Chinese strategies in the region; [the second-best] would be to ensure that their strategies do not align against Indian interests.” This triangle may therefore have reached “a precarious balance”: India is careful not to push Russia into China’s arms, while Moscow needs New Delhi as a counterweight to avoid excessive dependence on Beijing. Nevertheless, observers broadly agree that China is clearly “in the driver’s seat” in this triangle.

The Pakistan Question: Some Post-Pahalgam Lessons

Another point of attention for New Delhi is the discreet warming of relations between Russia and Pakistan, notably illustrated by Russian support for Pakistan’s inclusion in BRICS+. While the Russo-Pakistani partnership is in no way comparable to that of India, Russia and Pakistan have nonetheless developed their cooperation in recent years, for example, through joint exercises in October 2024 to strengthen their counterterrorism capabilities, something that is obviously not welcomed in New Delhi.

In April-May 2025, in response to the Pahalgam attack, India launched Operation Sindoor targeting terrorist groups based in Pakistan; this was followed by an escalation and a conflict with its Pakistani neighbour. In response to these developments, Russia immediately expressed concern and called on both sides to exercise “restraint.” The Russian Foreign Minister offered to mediate, despite India having consistently refused third-party involvement, particularly on the Kashmir issue. One can also question the influence of the China-Russia rapprochement on Russia’s measured stance in this conflict, especially given that Pakistan extensively deployed Chinese-origin military capabilities as part of its “Bunyan Marsoos” operation (in response to India).

A Partnership that Continues to Fit Within India’s Vision of a Multipolar Order

India continues to value its partnership with Russia, fully framing it within its vision of a multipolar international order and its broader perspective based on strategic ambiguity and autonomy. More than a deep partnership built on mutual trust, this relationship operates as a set of carefully calibrated signals, allowing New Delhi to preserve its strategic leeway while benefiting from the opportunistic advantages provided by its ties with Moscow.

An analysis of arms imports reveals the compatibility of the Indo-Russian relationship with India’s preferred model of cooperation: a flexible, issue-based approach based on specific converging interests rather than systematic alignment. Aware of the risks of excessive dependence, whether on Russia or any other partner, India pursues a pragmatic diversification while preserving its ties with Moscow. At the same time, New Delhi has been pushing to expand its arms exports, particularly of more advanced technologies, which in some cases compete with long-standing Russian monopolies, as exemplified by Armenia, where 43 % of imports between 2022 and 2024 came from India.

The assertion of this multipolar vision championed by New Delhi is also reflected in the way India and Russia cooperate within the BRICS(+), which India considers “a useful instrument for engendering multipolarity wherein [it] becomes one of the several great powers in the global system.”

***

As Vladimir Putin’s visit to India approaches in the fall of 2025, the Indo-Russian relationship appears as a relatively strong partnership, certainly tested in recent years, but still grounded in shared strategic interests. The return of Donald Trump to the White House could continue to reinforce this trend. As Subrahmanyam Jaishankar pointed out, “[the Trump administration] will change a lot of things. Some [policies] may be out of the syllabus, but we have to conduct foreign policy out of the syllabus in the interest of the country.” Consequently, maintaining the Russo-Indian partnership could prove all the more relevant under Trump 2.0, insofar as Washington’s more conciliatory attitude toward Moscow would make India’s position more sustainable. In this context, New Delhi’s rhetoric on the Ukrainian issue, according to which “this is not an era of war,” seems to be reinforced by Donald Trump’s comments, which Narendra Modi welcomed during his visit to Washington in February 2025.

However, this strategy is a double-edged sword. As analyst Ashley Tellis points out, while India may reap short-term tactical gains, it must not underestimate the damage inflicted on the international order by the Trump administration and by Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Contrary to India’s expectations, the “destruction of the liberal international order does not presage multipolarity, but rather consolidates the bipolarity that will subsist amid increasing entropy in global politics.” The hedging posture adopted by India, illustrated by Subrahmanyam Jaishankar’s remark that “Europe’s problems are not the world’s problems,” may have allowed it to navigate international challenges and pressure from its partners. Still, there is no guarantee that this strategy will be sufficient in the face of the Sino-Russian rapprochement. The post-Pahalgam conflict has, moreover, highlighted certain vulnerabilities of this approach.

Thus, the India-Russia partnership has withstood the tensions caused by the war in Ukraine, but its relevance as a deep strategic partnership, rather than merely a relationship of circumstance, could be called into question in an increasingly fractured world.

Comments are closed.