The U.S. presidential election demonstrated the tenacity of President Donald J. Trump’s ideas, policies and leadership style. The conservative nationalism and populism that marked his presidency continues to enjoy broad popular support and will not disappear with the inauguration of a Democratic president. U.S. allies will need to continue to consider the implications of this trend for U.S. foreign policy, the alliance system, and the future of the liberal international order. President Biden’s coming to power may therefore not bring about the long-awaited break with his predecessor and may increase the pressure on democratic allies in the areas of security and defence.

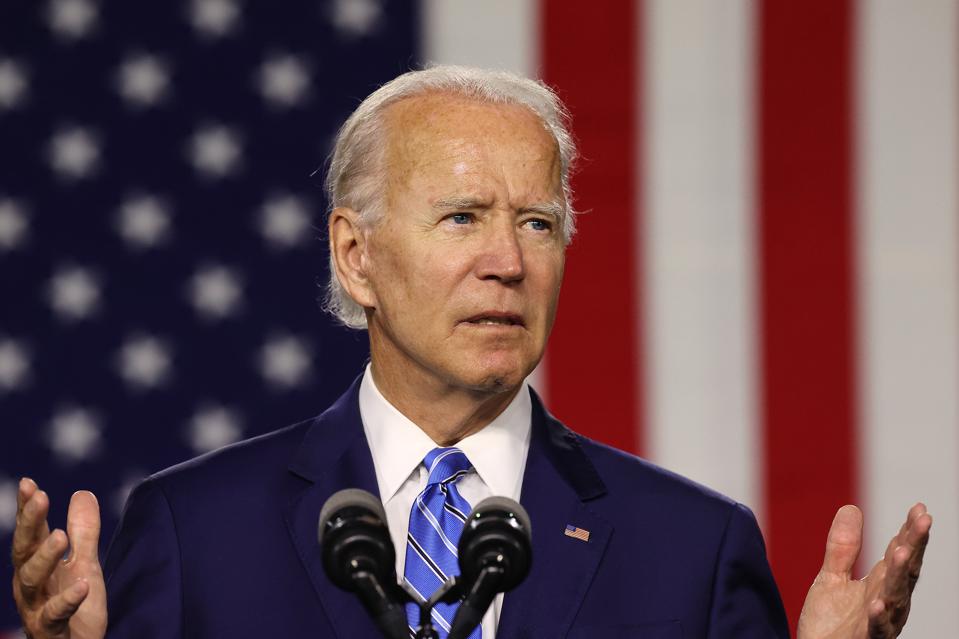

Continuity from Trump to Biden

President Trump has put forward a foreign policy marked by “conservative nationalism”, populism and protectionism, as well as a disdain for multilateral institutions and a transactional approach linking U.S. trade and security interests. These factors build on a long intellectual tradition in the U.S. and have been supported by many Republicans; it is now clear that these ideas remain popular among the American electorate.

Although President-elect Biden campaigned on an approach that was diametrically opposed to Trump’s, based on the return of liberal internationalism and American leadership, it will be difficult for him to make a profound break with the foreign policy of his predecessor.

First, he may have to contend with a Republican-majority Senate, which could constrain him in his choice of cabinet, and with the left wing of the Democratic Party in Congress, which could limit his international security ambitions. This faction aligns with the conservative nationalist movement’s promotion of the U.S. withdrawal from overseas conflicts and prioritization of domestic socio-economic needs, although it diverges on how to address these issues.

This prioritization of domestic affairs, combined with the management of the COVID-19 pandemic, socio-economic anxiety, racial tensions and widespread fatigue over “endless wars”, will lead President Biden to continue the U.S. military withdrawal begun under Barack Obama and continued by Donald Trump toward the end of his term. Thus, we can expect the continuation of the American military disengagement from Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as a reluctance to embark on new military ventures. The concept of the defence of human rights and democracy by military force does not seem ready to regain the upper hand in Washington. In this context, U.S. allies will continue to be called upon to compensate for the U.S. withdrawal, as evidenced by the strengthening of NATO’s military presence in Iraq.

Second, the political polarization and hyper-partisanship that marked the U.S. presidential election will lead the Biden administration to look inward to bridge the deep rifts that divide Americans and fuel political dysfunction. How can such a divided country forge consensus and provide global leadership? How can we not fear the transience and reversal of U.S. commitments, which vary with the U.S. electoral cycle? The U.S. political divide will undermine U.S. international leadership, which depends on the credibility and sustainability of U.S. engagement, particularly in terms of security assurances to its allies.

Third, some continuity is expected between the Biden and Trump administrations due to deepening geostrategic shifts. Despite growing polarization, a strong bipartisan consensus exists on the desire to maintain U.S. primacy in an era of intensified competition among major powers. The president-elect has expressed concern about the threat posed by China. He will therefore pursue a policy of competition towards Beijing and maintain a focus on the Asia-Pacific region.

Finally, as far as China is concerned, there seems to be a bipartisan consensus strong enough for the U.S. to push back. The American public is in agreement, since a majority of Americans have a negative opinion of China. However, Washington will need allies in order to be able to credibly influence, contain or deter China in the Asia-Pacific region. This is an area where the U.S. generally has the advantage: it has more friends in the world than both Russia and China. If Trump did not see this clearly, his newly fired Secretary of Defense, Mark Esper, understood it well: “Our global constellation of allies and partners remain an enduring strength that our competitors and adversaries simply cannot match”.

A Change in Leadership Style

These elements of continuity should not obscure the fact that a 180-degree break in style is to be expected in American management and leadership style under a Biden administration. Other than a friendlier and more conciliatory tone and the ability to engage in dialogue with counterparts, the biggest break that can be anticipated with Biden coming to power is the importance it will place on repairing bridges with America’s allies. In short, unilateralism will give way to multilateralism.

With Biden’s victory, the U.S. will quickly benefit from a radical shift in international public opinion. A recent survey by the Pew Research Centre found that ratings of the U.S. are at their lowest level in two decades. The situation can only get better. But will world leaders also be forgiving? Looking back to the immediate post-Bush period, when Barack Obama came to power, experts were not very optimistic about the restoration of good relations with allies. The U.S. succeeded, however, despite the transatlantic rift that had existed since the beginning of the Iraq war in 2003. That said, while the allies can deal with disagreements, they do not respond well to surprises and unpredictability, which is what they have experienced over the past four years.

Biden’s approach to China’s containment will be based on concerted action with allies in the region and the U.S. will share with them a desire to avoid escalating tensions and the instrumentalization of multilateral institutions in order to foster sectoral cooperation with China. This approach, which will be articulated at a Summit of Democracies, will seek stronger commitments from U.S. allies to mobilize and coordinate their efforts to curb Chinese authoritarianism and aggression.

With respect to Russia, the Biden administration will seek to reaffirm U.S. security commitments within NATO, take a firm stance vis-à-vis Ukraine, and continue the focus on collective defence that began in 2014. That said, President Biden will quickly seek avenues for cooperation with Russia, beginning with the extension of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, which expires in February 2021.

While Trump is often credited for the fact that NATO allies have increased their total defence spending by $130 billion since 2016, his tolerance of authoritarianism has also allowed for democratic backsliding in Poland, Hungary and Turkey. This ultimately erodes NATO’s political cohesion and, by extension, the credibility of its deterrence posture. While NATO’s military strength remains impressive, the credibility of its signalling to Russia and other adversaries is undermined by political disunity. The current tensions surrounding Turkey illustrate the possible dangers of a breakdown of cohesion within the alliance.

While Trump has shown disdain for traditional alliances, he has fared much better with allies of convenience, which are transactional in nature, like his diplomatic style. However, the most important adjustment will not be with the U.S.’ traditional allies, who will at least be enthusiastic about strengthening international institutions through greater U.S. engagement, but with rivals such as Russia and China. President Trump has even encouraged these regimes, at times expressing admiration for Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping’s leadership styles. How will Biden restore the credibility of the U.S. and succeed in deterring opponents?

The firm and concerted approach that Biden will prioritize in a context of increased competition among major powers will require greater input from U.S. allies and closer ties with emerging democracies such as India and Indonesia. This will require renewed efforts to increase joint military exercises, pooling of military procurement, a sustained increase in defence budgets and level of preparedness of military forces, as well as more equitable burden-sharing in an uncertain economic context due to the pandemic. While it will be easier for allies to work with a Biden administration, it will also be harder to say no to the expression of renewed American leadership and the requests for support that will come with it.

Biden’s U.S. foreign policy will have to convey an uncompromising stance on the principles and values enshrined in the Washington Treaty, NATO’s founding treaty. By leading by example, the U.S. will have at its disposal one of the best strategies to counter Russian and Chinese rhetoric. It may also be necessary to reaffirm ad nauseam the argument for international institutions and multilateral diplomacy, since the forces of nationalism, protectionism and right-wing populism in the U.S. will not disappear overnight.

Policy Considerations and Recommendations

In the past four years, have Canadians become desensitized to Trump’s threats and intimidation? When Biden arrives at the White House, the Trudeau government or any successor will have the task of restoring the country’s status as a close ally and partner of the U.S. Canada has had to hedge or stall because of Trump’s mercantilist tendencies, but there are important decisions ahead that can no longer be postponed, from intelligence cooperation to continental defence, with the modernization of NORAD. The silver lining of dealing with the Trump administration for four years and surviving monumental diplomatic challenges such as the renegotiation of NAFTA is that Canada’s negotiating capabilities have been sharpened. There is no doubt that important lessons have been learned from this process, as well as the establishment of important contacts between Ottawa and Washington. This, Ottawa can continue to capitalize on. With Biden at the helm, Canada and the U.S. will not be perfectly aligned – they never have been – but Canada will benefit from a more predictable bilateral relationship (at least for four years) and this will be a huge victory in and of itself.

Some issues will remain difficult to resolve regardless of who holds the White House, such as Canada’s bilateral relationship with China. On other issues, Canada should build on what has worked well in the past. Leading NATO missions has been one such example, and Canada should consider doing the same in the context of the United Nations. Taking on command positions allows for greater control over the parameters of intervention and greater visibility within these institutions. It is more important for Canada to make a significant contribution, with tangible impact, and receive the recognition that comes with it, than sending symbolic contributions across many missions in what is often called contribution warfare, which means displaying your flag in as many places as possible rather than leading. The impending end of the Canadian command of the NATO mission in Iraq also provides an opportunity to invest in a UN mission to enhance Canada’s peacekeeping credibility.

Finally, it should be easier to promote Canada’s feminist foreign policy now that its closest ally is no longer led by a misogynist and a racist. Above all, it is time for Canada to update its foreign policy vision by undertaking the same type of consultations it conducted in 2016 for defence policy. The political transition in the U.S., combined with the global pandemic and a more antagonistic China, should be reason enough to undertake this exercise.

Comments are closed.