Without turning away from counterterrorism, U.S. defense seems to be increasingly orienting its focus on China in an era of great power competition. Yet China is not the only challenge the United States faces in a multipolar world. The United States, a world power in relative decline, wishes to preserve the status quo that favors its hegemony. This is evident in the Biden administration’s desire to undo Donald Trump’s policies and restore U.S. leadership and reputation on the world stage. The United States, a power with global ambitions, is currently seeing a renewal of its strategic planning. However, what are the foreseeable changes to the strategic planning? And do they have the means to achieve their ambition? This policy brief examines the security priorities of the Biden administration, its positioning vis-à-vis the European Union, the U.S. strategy in the Indo-Pacific, and the one-war concept that the United States seems to favor.

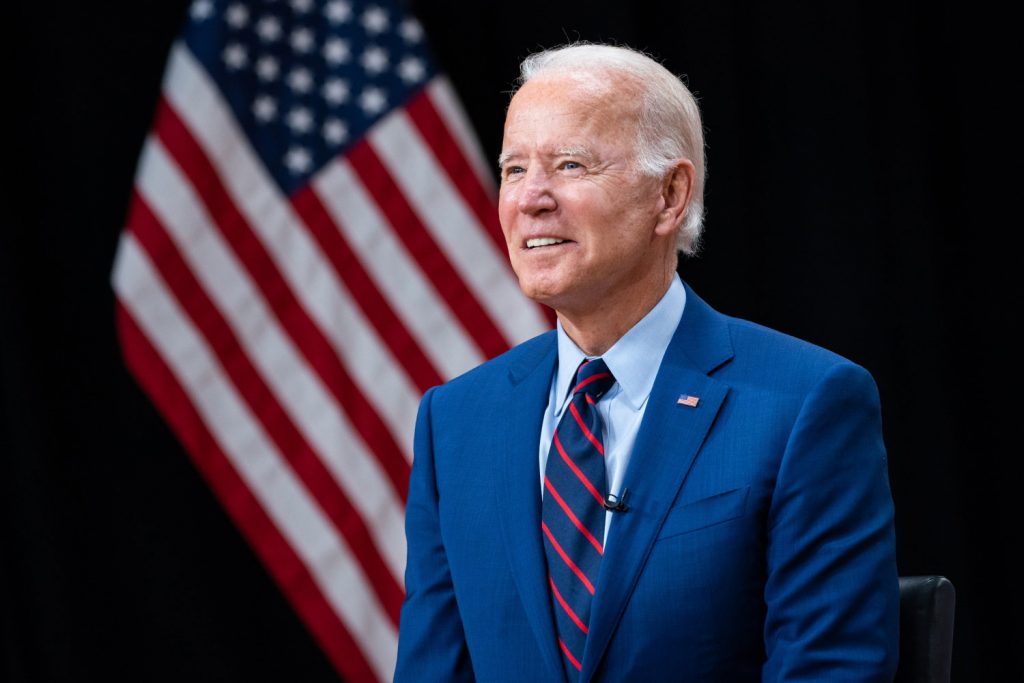

National Security Priorities of the Biden Administration

A key national security priority of the new Biden Administration is to defend American primacy, to deter and prevent adversaries from directly threatening the United States or its allies, as well as to prevent their domination of key regions. To do this, the United States intends to lead and support a stable and open international system based on strong democratic alliances, multilateral institutions, and rules. The Biden administration emphasizes that the United States cannot achieve these goals alone and must rely on its allies and partners around the world, including NATO, Australia, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand, Singapore, Vietnam and ASEAN. While it appears that these national security priorities are heavily weighted toward the Indo-Pacific region, the new national security strategic direction also mentions a strong re-engagement with the European Union while continuing the fight against terrorism and deterring Iran with regional partners.

For its part, the Department of Defense identifies China as its primary challenge against which it wishes to develop the appropriate concepts, capabilities and operational plans to strengthen deterrence and maintain U.S. competitive advantage. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence’s new 2021 Annual Threat Assessment also identifies China, as well as Russia, as significant threats, emphasizing China’s global ambitions and Russia’s provocative actions.

Europe, the Indispensable Partner

If competition with China becomes increasingly central to U.S. grand strategy, it is likely that the United States will view other regions of the world through this competitive lens, and then seek support from its partners and allies in its rivalry with China. The Trump administration had already sought to engage European countries in its opposition to China, including pushing for the banning of Chinese company Huawei from European countries’ 5G telecom infrastructure. According to Simon, Desmaele and Becker of the Institute in European Studies at Vrije Universiteit Brussel, the United States faces two important challenges in Europe regarding its rivalry with China. First, U.S. resources are not unlimited. If it makes China its strategic priority, it will have fewer resources to play a proactive role in Europe, leaving regional actors to exert their influence. However, since the United States wants to maintain a certain balance in Europe, especially vis-à-vis Russia, it will have to rely on the United Kingdom and France to help it maintain balance on the European continent. Second, the United States wants to expand its strategic considerations in Europe to counter the growing influence of China. To do this, the United States must ensure that European partners and allies do not overreach China, that China and Russia do not divide European countries, and that European countries support U.S. strategic objectives in the Indo-Pacific. The question remains as to how European countries will behave in the face of Sino-American competition. While the European Union’s recent strategy for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific suggests a consensus on an Asian pivot for the EU, the reality is that there are different opinions on the role of the Indo-Pacific in the EU’s international policy. Thus, while France, Germany and the Netherlands are ready to commit themselves militarily to the Indo-Pacific region, this is not the case for other European countries that prefer neutrality. Moreover, the differences are also felt between France and Germany. While France openly wishes to counteract Chinese hegemony and stabilize the region, Germany places more emphasis on economic opportunities.

U.S. Military and Strategic Planning in the Face of Great Power Competition

Whereas U.S. defense prepared for several decades to defeat multiple regional adversaries in succession in medium-sized wars, it now plans a single standard of war aimed at defeating a rival great power capable of matching U.S. power. This new strategy prepares the United States to confront one great power, such as China or Russia, rather than several weaker opponents such as Iran and North Korea. This is the most significant change in U.S. strategic planning since the end of the Cold War.

This new strategy also requires new force planning and, more importantly, new capabilities to defeat the enemy. The United States appears to be focusing on capabilities of deterrence by denial, either to deter the adversary from launching an attack if it is unlikely to succeed, or to destroy the enemy’s attack capabilities before they are used. This would include, for example, the ability to strike multiple targets within the adversary’s territory to destroy its force projection capabilities. This is the Third Offset strategy, developed since the Obama administration, which emphasizes superiority through new technologies and deterrence. This strategy is designed to address several operational challenges such as Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD), guided munitions, undersea warfare, cyber warfare, and technological warfare. It specifically targets Russian and Chinese capabilities, especially in A2/AD. In theory, the strategy of deterrence by denial is very effective against a revisionist power. The ability to protect its territory and allies, and the ability to destroy the opponent’s force projection capabilities would be more effective than alternatives, such as punishment deterrence or strategic withdrawal.

Abandoning Control of the Indo-Pacific Seas?

Faced with the budgetary constraints inherent in any public action, some suggest that the United States should abandon control of the seas in the Indo-Pacific and concentrate on a less costly strategy. First, the reason that the United States is seeking maritime superiority in the Indo-Pacific is because otherwise China would fill the space left by the U.S. withdrawal. However, it is not clear that China will fill the void left by an American withdrawal. Second, there is a strategic risk for the United States in seeking maritime control of the Indo-Pacific – a risk of distance. When its maritime power is projected to be of great distance from U.S. shores, U.S. forces are particularly vulnerable against measures designed to increase access costs, making the United States dependent on allied territories to support deployed forces through bases, infrastructure, and logistics. Second, as the costs and risks of maintaining access increase, the asymmetric issues become more defined for the United States. This is especially true now that China can inflict heavy costs on the United States through the development of sea, submarine, air, sea, and land ballistic missile capabilities enabling an A2/AD strategy. It would then be easier, less risky, and less costly to ensure that control of the seas is denied rather than exercised. The ambition for primacy in this region would then have to be abandoned.

The Vulnerabilities of the One-War Strategy

Despite the advantages of the one-war strategy based on deterrence by denial discussed above, there are many risks, challenges and grey areas. The first risk is obviously if the United States is faced with two or more wars at the same time. The United States would then face a dilemma in distributing the war effort across multiple theaters of operation. It may be argued that if the United States demonstrates its ability to win the first war quickly, it will deter the second adversary from attacking, or advancing its interests. However, any war has its share of uncertainties and there is no guarantee of a quick and decisive victory. Second, even in the event of a quick and decisive victory by the United States, the U.S. modus operandi will be revealed, as well as potential vulnerabilities that an adversary could exploit in a second theater of operation. Finally, it is important to remember that a country that starts a war is a country that believes it can win it. Overconfidence bias can alter or even diminish the supposed deterrence of a quick and decisive victory over the first adversary. The second U.S. strategy for dealing with a second theater of operation would be to delay retaliation until the first war is won. However, this may allow the second adversary to change the status quo to its advantage in a particular region, reshuffling the deck, which highlights the need to rely on regional allies.

The second limitation of the one-war strategy of deterrence by denial is the willingness of a policymaker to respond to an adversary’s initial use of force. The United States might be reluctant to respond to a show of force if it is unsure of the adversary’s motivations. The United States should clearly define the type of military action to which it will respond by destroying the enemy’s offensive capabilities.

Finally, an important challenge remains the credibility of the United States to use force when it is not directly targeted. How willing is the United States to go to war to protect a partner when it is difficult to distinguish between a provocation, an isolated attack, or the beginning of a series of military attacks? For example, China might begin maritime military maneuvers near Taiwan or use force against a foreign ship. The response to such maneuvers or attack will depend on whether they are correctly interpreted. It will have to be determined whether they are simply provocations, an isolated attack, or whether the naval maneuvers or use of force against a ship are the beginning of a larger military engagement.

Intelligence Capacities as an Indispensable Tool

The United States cannot implement its new strategy without first developing its intelligence capability to support that strategy. Intelligence is required to understand and anticipate adversary doctrines, prevent tactical and operational surprises, and ensure that U.S. military capabilities are not compromised before going into action. In the face of Chinese and Russian technological capabilities, intelligence must now more fully integrate the cyber, digital, and space domains, while being appropriately assimilated into command-and-control functions to ensure rapid decision-making.

More than ever, intelligence cooperation must also be facilitated not only for intelligence sharing, but also for joint action. This is especially true within the Five Eyes, the most institutionalized of intelligence partnerships. For example, in the cyber and space domains, the ability of the Five Eyes signals intelligence (SIGINT) agencies to monitor, analyze and penetrate adversaries will prove a critical asset in future conflicts. Beyond this closed circle, intelligence agencies need to strengthen their collaboration with other countries, such as Japan and Germany, particularly in support of U.S. strategy in Europe and the Indo-Pacific. Recent statements about the creation of two mission centers on China by the Central Intelligence Agency reflect the importance of intelligence in American strategy to counter China.

Considerations for Canada

One of the most important questions in the face of current U.S. strategic positioning is where Canada fits into the U.S. strategy and what role Canada should or could play. While it is relatively certain that the U.S. will seek some form of support from Canada in its new strategic direction, the Canadian position is far from clear at this time.

Canada should therefore rethink its foreign policy in light of new developments on the international scene and the strategic repositioning of its main ally. Canadian foreign policy must reflect Canada’s national interests, but also alliance interests, particularly those of the United States and NATO. Clear strategic directions, consistent with Canadian foreign policy, will also have to be formulated.

On the intelligence front, David Vigneault, Director of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), reiterated that China is one of the primary threats to Canada’s national security. In this area, Canada could increase its cooperation with allies in the Indo-Pacific region, particularly in the area of cyber intelligence. While the United States uses intelligence as one of its preferred tools to deal with China, Canada should not fall into the trap of relying solely on American intelligence, which may be useful but does not necessarily reflect Canadian interests. The development of Indo-Pacific intelligence expertise would be the best way for Canada to have an understanding of the environment and to act on its interests.

It is unlikely that Canada will play a leading role in the Indo-Pacific soon. Traditionally, this region has not been of primary interest to Canada. However, Canada must be prepared to contribute in some way to American efforts in the region. These contributions, which can be of various kinds, may include strengthening Canada’s military presence in the Indo-Pacific, enhancing diplomatic relations with certain countries in the region, or engaging with existing forums such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad).

However, any contribution in the Indo-Pacific should not be at the expense of Canadian national interests. For example, the U.S. proposal to expand the role of the Five Eyes in the Asia-Pacific to better contain China does not appear to be an option that Canada should support. Indeed, New Zealand has recently stated that it does not support an expanded role for the Five Eyes to pressure China. The possibility of retaliation by China is likely to hit middle powers like Canada the hardest. For example, China’s ban on the import of Canadian canola would be a retaliation against Canada for the strained relations between Beijing and Ottawa, just as the arrest of two Canadians in China would be a retaliation for Huawei’s Meng Wanzhou case. Besides, the two Canadians, as well as two Americans, were released after an agreement between the American justice system and Meng Wanzhou, which suggests at first glance that hostage diplomacy has worked. Moreover, Canada does not have unlimited resources, and an increase in defence budgets for a contribution in the Indo-Pacific is not currently being considered. Thus, if a significant contribution were to be made in the Indo-Pacific, it would be at the expense of other commitments or national priorities, such as the Arctic or Eastern Europe.

Comments are closed.