|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

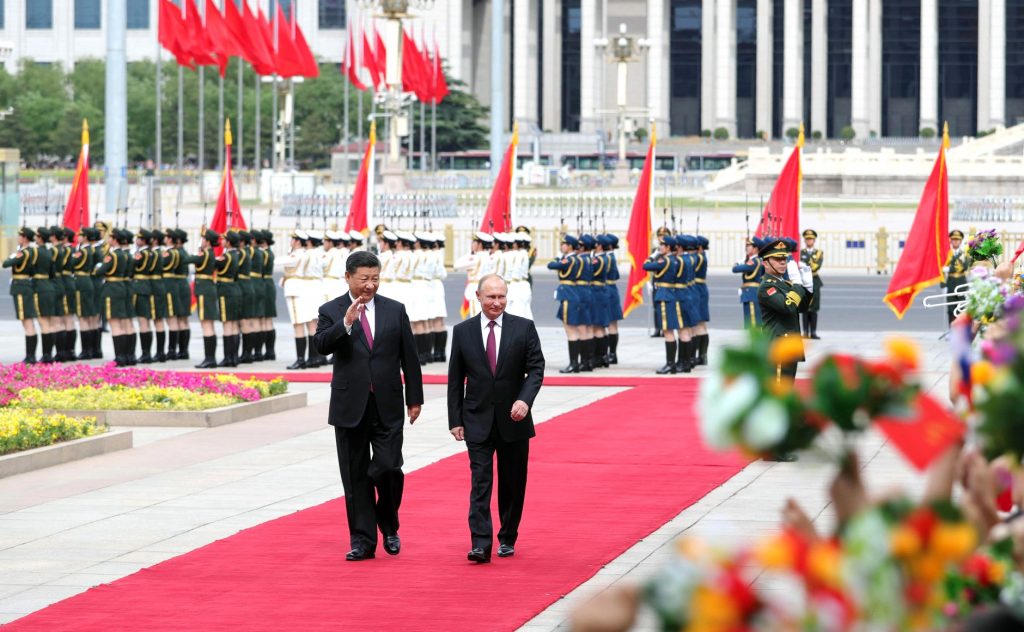

This policy report argues that the current war in Ukraine is unlikely to break the Chinese-Russian unlimited partnership and will accelerate the world’s bipolarization. China has political, energetic, and strategic interests in collaborating with Russia. China will not lose sight of its strategic partnership with Russia until reunification with Taiwan is accomplished, further polarizing the international system in the process. However, China has too much to lose economically were it to embrace Russia’s cause in Ukraine unambiguously. This constitutes leverage that the West could use to draw a wedge between China and Russia. The West, most especially the U.S., should also balance its strategic competition with China by increasing cooperation on shared interests like climate change, nuclear proliferation, and pandemic prevention. Lastly, Washington should reduce Chinese fears about regime security and Taiwan because such fears are driving China’s closeness to Russia and exacerbate an already tensed U.S.-China strategic competition.

***

Today, there are clear signs, such as export restrictions or financial restraint, demonstrating the People’s Republic of China’s (China) unwillingness to align with the Russian Federation (Russia) in the current war in Ukraine completely. Other signs, however, indicate China’s implicit backing of Russia’s actions: the coverage of the war by pro-Russia Chinese state-controlled media; and China’s absence of condemnation of Russia’s violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty despite the importance of sovereignty in Chinese foreign policy. To be sure, Beijing has no appetite for war in Ukraine as the latter is an important transit hub part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Nor has China any interest in seeing the return of war in Europe which could seriously destabilize its primary export market and impede China’s economic interests in various ways. This being said, on February 4, 2022, China issued a joint statement with Russia unveiling a new strategic partnership with no limits. Although not a formal military alliance, it’s just like it. This partnership reflects China-Russia’s long-term strategic collaboration reaching new heights as both countries acknowledge, for the first time, each other’s crucial concerns: NATO’s eastward expansion and the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy.

Is the war in Ukraine a turning point sealing a bipolar order where China and Russia form a geopolitical block and the West another? This analysis sheds light on the evolution of the Sino-Russian partnership from the 2000s to this day to answer this question. China and Russia share an ideological affinity for authoritarianism, and their partnership is based on three central pillars. The first is political and diplomatic opposition to the U.S., particularly at the United Nations (UN). China and Russia both want political security for authoritarian regimes against what is perceived as the U.S. hegemonic liberal threat. The second pillar concerns Sino-Russian defence cooperation and encompasses military exercises and arms sales. The third pillar is about economic complementarity: China needs commodities, while Russia needs export markets for its commodities.

This analysis is structured as follows: First, I trace the evolution of the Sino-Russian partnership from the 2000s to the present in order to illustrate the partnership’s continued solidification with a dramatic acceleration starting in 2014. Based on this analysis, I argue that the bipolarization of the world is underway, prior to formulating a few recommendations for the Western block to drive a wedge between China and Russia to attenuate this phenomenon.

The Sino-Russian Bilateral Relationship From 2000 to 2014: Political and Diplomatic Cooperation

The USSR and China have had a complicated history throughout the 20th century. At the beginning of the Cold War, in 1950, both countries signed the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance. This alliance significantly impacted the balance of power during the Cold War but was short-lived for various reasons. The alliance lasted only nine years and ended in 1959 with the Sino-Soviet split. The Soviet Union and China went from allies to acrimonious rivals. In 1985 started the Sino-Soviet rapprochement where both camps tried to work with each other to set up a modus vivendi. With the fall of the USSR in 1989, another period of Sino-Russian normalization was initiated.

On the eve of the 21st century, we started to see serious political and diplomatic convergence between China and Russia. In March 1999, Russia sponsored a resolution in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) during the Kosovo war, demanding the immediate cessation of force against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. China voted in favor of this resolution even though it did not cosponsor it. This event is an important moment in China-Russia diplomatic collaboration. The bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade during the 1999 Kosovo War by the U.S. shifted China’s vision of Washington’s motives, still believing that the bombing was intentional. Since that event, China and Russia have increasingly become annoyed of what they see as the threat of Washington’s military superiority and willingness to advance its interests independently of international law and regardless of the legitimate interests of other states. Such suspicion is the political bedrock of the Sino-Russian UNSC cooperation.

Since the beginning of the 2000s, China and Russia have politically managed to fix many of their long-standing issues. In 2001, both countries signed the Sino-Russian Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation (renewed in 2021). This was a significant advancement in the normalization of the Sino-Russian bilateral relationship initiated in 1989. The normalization process culminated in 2005, with China and Russia settling a border dispute that had caused skirmishes between China and the USSR in 1969. In 2003, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) was established by China and Russia with other Central Asian countries. The SCO is the principal multilateral organization that China and Russia rely on to advance their security interests in Central Asia, especially coordinating military exercises between its members. Despite enduring mutual suspicions, China and Russia have increasingly worked together in international bodies. In 2003, China and Russia, among other countries, vigorously opposed the Iraq War and the U.S. “Coalition of the Willing,” denouncing U.S. unilateralism which circumvents the UN to launch a preemptive war with the objective of regime change. Later on, in 2007, China and Russia cast a joint veto on a U.S.-sponsored UNSC resolution regarding human rights violations and political repression in Myanmar. This vote was the first of an enduring strategic Sino-Russian diplomatic cooperation manifested in jointly vetoing UNSC resolutions.

Since normalization, the 2008 Georgian War was the first significant turbulence in the Sino-Russian partnership. When Russia invaded the Georgian territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, China’s vision of Russia was negatively impacted. Moscow recognized these two territories as independent states, while it failed to get China and other SCO states to recognize these new pro-Russia entities during a summit in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, a few weeks after the Russian invasion. Nevertheless, Russia at least managed to secure China’s abstention on voting a UN resolution condemning its actions. However, China never fully endorsed Russia and was arguably quite unhappy with Moscow’s actions in Georgia. This is unsurprising given China’s insistence on respect for sovereignty and its own separatism problems (Xinjiang, Tibet, Taiwan). On the other hand, this friction did not stop the two countries from 2007 to 2012 from jointly casting five more vetoes in the UNSC. And since this period, the Sino-Russian partnership tractions the emerging economies grouping named BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), advocating for an economic and political multipolar international order.

Military Cooperation and Arms Sales

With the normalization of the Sino-Russian relationship, both countries have considered defence and security ties as crucial areas of cooperation, in addition to the political-diplomatic collaboration. Defence cooperation, the second pillar of Sino-Russian cooperation, stands on two legs: military exercises and arms sales. This focus is reflected in the 1996 “Partnership of Strategic Coordination Based on Equality and Benefit and Oriented Towards the 21st Century.” In 2011, this mechanism was elevated to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership. These documents have facilitated the Sino-Russian high-level cooperation on various topics, such as joint military exercises, arms sales, and regional and global security discussions. The “China-Russia Staff Headquarters Strategic Consultation” has been held every year since 1997 and is a central meeting to manage cooperation between the two militaries.

Military exercises joining Chinese and Russian armies are either bilateral or multilateral. In 2003, Chinese and Russian armed forces organized their first combined military exercise under the SCO framework. In 2005, a peace mission was organized under the SCO and the Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation. Another significant step was taken in 2012 with an annual bilateral Joint Sea exercise. From 2003 to 2014, China and Russia participated in 20 military exercises of all sorts, both conducted bilaterally or multilaterally. These joint exercises have increased the Chinese and Russian armies’ interoperability, even though both armed forces are not as interoperable as NATO’s members. Such exercises have nonetheless been effective for increasing operational capabilities, mutual trust, and a common defence culture (in the last two decades, many Chinese and Russian military officers have been formed in Russia and China, respectively).

The other leg of defence cooperation is arms sales. The early to mid-2000s were great years for the Sino-Russian defence business: China imported 87% of its arms from Russia. China was thirsty for non-Western foreign arms imports because of the sanctions resulting from the Tiananmen Square crackdown and a desire to upgrade its military. And Russia was eager to export outdated military technology and licenses to compensate for its lack of internal absorption as the country was going through economic hardships. However, Russia was unwilling to export its most sophisticated technology because of the Chinese reverse engineering of Russian higher-end military systems and because of security concerns. China’s military imports from Russia have helped it improve its own defence industry as well as power projection (especially over Taiwan) and defensive capabilities. Such procurements comprised jet fighters (Su-27 and Su-30), surface-to-air missile defence systems (S-300), Sovremennyy-class guided-missile destroyers, and Kilo-class submarines. From 2002 to 2007, China imported around $2.3 billion of military equipment from Russia on average. After peaking at $3.2 in 2005, there was a significant reduction from 2006 to 2014, with revenues averaging $600 million annually.

Economic Cooperation

On the economic side, more broadly, which is the third pillar of the Sino-Russian partnership, total bilateral goods trade was relatively modest, although the trend was increasing: $7.1 billion on average between 1997-2002, $15.5 between 1997-2007 and 73.6 between 2007-2017. In the early 2000s, around 60% of Russian exports to China were chemicals, pharmaceuticals, machinery, transport equipment, and manufactured goods. In contrast, China’s exports to Russia were mainly low capital-intensive and high labor-intensive manufactured goods. There were also minimal services and foreign direct investments (FDI). This started to change from 2007 to 2012. Russian exports of fuels and minerals reached 75% of the country’s total exports to China. As for China, it kept exporting manufactured goods to Russia, although more sophisticated ones. And for energy cooperation, the only significant project, the East Siberian-Pacific Ocean oil pipeline, was announced in 2006 and funded by China. The pipeline opened in 2011 and was the first of its kind to link the two countries, allowing for increased energetic integration. From the 2000s to 2014, the Sino-Russian relationship was characterized by moderate economic complementarity.

From the 2000s to 2014, the three pillars of Sino-Russian cooperation – political-diplomacy, defence, and economy – were deepening, although they remained constrained by various factors. On the military and political aspects, Russia was still uneasy about exporting sophisticated arms systems to China because of long-lasting fears regarding China’s ambitions in Russia’s Far East and the potential use China could do against Russia of its exported advanced military systems. However, military-to-military links and joint military exercises have blossomed during this period (2000-2014) and have helped increase mutual trust and interoperability. This rapprochement was translated diplomatically with similar votes to counter the U.S. in the UNSC. On the other hand, energetically speaking, the infrastructures required for deep energy cooperation were lacking as most Siberian gas fields were connected to Europe by pipelines. But China’s growing energy needs were to be increasingly met by Russia after the Kremlin’s foreign policy reorientation in 2014 with Crimea’s annexation.

2014-2022: The Acceleration of the Sino-Russian Partnership

Political-diplomatic Cooperation

Since the annexation of Crimea, Russia and China have become closer in all aspects of their relationship. Just like China did in 2008 after Russia attacked Georgia, Beijing abstained from voting in favour of UNSC resolutions invalidating the results of a referendum separating Crimea from Ukraine to make it part of the Russian Federation. Nonetheless, China did not publicly endorse Russia’s position, even though Xi admired Russia’s 2014 operation in Crimea because Putin boosted his domestic popularity and secured his country “a large piece of land and resources.” Despite Xi’s admiration, Chinese financial institutions have demonstrated strict compliance with the sanction regime because of fear of secondary sanctions, even though China always rhetorically opposes Western sanctions. As a result, Russia has struggled to issue debt or equity on the Chinese stock market. Only a handful of Chinese political banks – the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China – have provided funds to Russia’s sanctioned entities. These banks are less connected to the global economy than other Chinese banks and, by extension, less subject to secondary sanctions. In any case, Beijing has always managed to provide financing for crucial political bilateral deals.

Furthermore, a year after Crimea’s annexation, Xi and Putin managed to sign an agreement to frame what were initially competing transnational political-economic projects as complementary: China’s BRI and Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). Russia reevaluated China’s ambitions in Central Asia, which had previously been understood as competitive with minor areas of cooperation, given Russia’s willingness to maintain its preponderance in the post-Soviet sphere. Moscow did not like the growing Chinese presence in Central Asia but had to compromise with Beijing because of Western sanctions resulting from Crimea’s annexation. This new reassessment paved the way for deeper cooperation and became a turning point in the two countries’ relationship.

This political cooperation translated into the diplomatic level, especially at the UNSC. In 2017, China and Russia used for the sixth time their vetoes to block a UNSC resolution supported by the West to sanction Bashar al Assad’s regime regarding its use of chemical weapons in Syria. In 2021, China and Russia supported the suppression of economic sanctions against Afghanistan. They called for the unfreezing of the country’s assets by vetoing a UNSC resolution to hold accountable the Taliban regime. One could also mention the Sino-Russian cooperation to attenuate sanctions imposed on North Korea and Iran. China and Russia have closely worked in multilateral institutions like the G20, APEC, the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia, Xianghsan Forum, ASEAN Defense Ministers Meeting Plus, and the Shangri-La Dialogue. The expansion of such multilateral meetings related to security matters has proven to be occasions for high-level military officers from China and Russia to meet and coordinate on the side of the events.

Economic Cooperation

Another significant Sino-Russian rapprochement since 2014 pertains to the economic and technological realms. After Crimea’s annexation, Russia decided to reorient the Russian economy towards China. The goal was to facilitate Chinese investments in large infrastructures and energy-related projects to exploit Russia’s natural resources and massively sell hydrocarbons and agricultural products to China. A megadeal of $400 billion was signed in 2014 for Russian gas exports to China through the Power of Siberia pipeline (pumping 38 billion cubic metres of gas annually), which was completed in 2019. In 2014, the Russian and Chinese central banks set up a 150-billion-yuan ($24 billion) swap line, renewed every three years to facilitate bilateral commerce despite sanctions. This is part of a de-dollarizing effort by the two countries to reduce the U.S. dollar’s share in bilateral trade. Today, the U.S. dollar represents 40% of Russia’s exports to China compared to almost 100% in 2013. Russia’s dependence on China for export markets and credit lines has kept increasing because only China has the economic wherewithal to provide massive loans to Russia and absorb its energy production. China represents 17.3% of the global GDP, while Russia accounts for only 1.7%.

Moreover, there are major ongoing technological projects and collaborations. In 2014, China and Russia created the “China Russia Commission on Important Strategic Satellite Navigation Cooperation.” The China National Space Administration and Russia’s Federal Space Agency have jointly worked, since 2015, on developing space components for their respective satellite navigation systems: Beidou and GLONASS. We can also see cooperation taking place on aero-engine technology. In 2017, the China Aviation Research Institute signed a memorandum of understanding with Russia’s Central Institute of Aviation Motors. In 2020, China and Russia agreed to enhance such collaborations by establishing a roadmap for science, technology, and innovation until 2025. As part of this initiative, there is, among other things, a joint investment fund for high-tech projects to develop cooperation on critical domains like artificial intelligence research. This list is far from exhaustive as collaboration also involves nuclear power generation, high-speed rail, and other infrastructure development. Technological cooperation has dramatically expanded since 2014.

On top of that, in 2020, Russia became China’s most significant source of oil imports, displacing Saudi Arabia. And Gazprom, Russia’s biggest gas company, ambitions to triple its gas exports to provide for half of the Chinese demand. Russia also took advantage of the 2018 Sino-American trade war to boost its exports of minerals and foods to China. On February 4, 2022, Putin and Xi signed two additional agreements to expand gas and oil cooperation representing $117.5 billion. That same day, the two leaders also signed dozens of other deals on trade and investment, anti-monopoly, sports, satellites, digitalization, and other areas of cooperation. And a month before this meeting, China had already lifted a ban on wheat coming from certain Russian regions to increase agricultural imports. Last but not least, China and Russia announced in January 2022 that they would jointly build a new gas pipeline, Power of Siberia 2, which should start operating in 3 years to carry up to 50 bcm annually.

To give a few numbers, the China-Russia trade reached $146 billion in 2021 compared to $68 billion in 2015. Chinese main exports to Russia centered around telecommunications, aviation, media industry, and stuffed toys, while Russia mainly exports hydrocarbons and agricultural products to China. The dollar’s share of Sino-Russian total economic exchanges was under 50% for the first time recorded in 2020, while it constituted around 90% of such interactions in 2014. In 2021, 17% of bilateral trade was conducted in yuan. Russia detains $140 billion in Chinese debt (four times bigger than in 2018), while China holds 14.2% of Russia’s foreign-exchange reserves. In 2021, the dollar represented merely 16% of Russia’s $640 billion in foreign reserves against 46% in 2017. The yuan accounted for 13% ($77 billion) of such reserves in 2021. China exported $70 billion of goods to Russia in 2021, significantly more than in the 2000s. However, it remains small relative to Chinese exports to the European Union and the United States, totalling around $1 trillion. Since 2014 and Crimea’s annexation, Sino-Russian trade increased by roughly 50%, and China has become Russia’s primary export market.

Military Cooperation and Arms Sales

Crimea’s annexation has also triggered deeper military-to-military cooperation, especially in 2017 with the signing of a new roadmap for military cooperation. Since 2014, Joint Sea exercises (organized for the first time in 2012) have taken place in each other’s regions of interest. For example, the 2014 Sino-Russian naval drills took place in the East China Sea near the contested Senkaku Islands, while in 2017, China returned the favor and accepted to train in the Baltic Sea. In 2016, China and Russia conducted for the first time an Aerospace Security Exercise. This maneuver was centered around Sino-Russian “air, and missile defence, operational and mutual fire support, and ballistic and cruise missile strikes.” Very important too, China has been included in Russia’s Annual Strategic Command-staff Exercise since 2018. This is a major solidification of Sino-Russian defence ties. Historically, only former Soviet states have participated in this exercise which mobilizes Russia’s four strategic commands to simulate a major power war. In 2019, the People Liberation Army Air Force and the Russian Aerospace Force organized a joint strategic aviation patrol for the first time. As part of this exercise, several Chinese H-6K and Russian Tu-95 bombers did not shy away from entering the South Korean and Japanese Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) for training purposes. Other military exercises include Apprehension of Illegal Border Crossing Exercise, Disaster Relief Exercise, Antiterrorist Exercise, and River Port Emergencies Exercises. The two countries also regularly engage in international military events like tank biathlons or the International Army Games. China and Russia have conducted 28 military exercises since 2003, with the variety and complexity of such exercises expanding since 2014, which expresses mutual friendly intentions.

Joint military exercises are valuable to ameliorate interoperability and improve mutual understanding, notably overcoming linguistic and cultural obstacles. They also provide the Chinese and Russian military leaderships a chance to interact and collect intelligence on the other army’s capabilities, defence culture, and combat methods. Moving forward, the next logical step of Sino-Russian military exercises will probably concern cyber, drones, electronic warfare, outer space, and the use of artificial intelligence in military systems to guide hypersonic missiles and other weapons.

Since Russia’s annexation of Crimea, arms sales are not left out either. Russia concluded that since China’s industrial-military production is catching up fast, it should take advantage of the window to sell arms while it can. Thus, the decision to suspend the de facto ban on selling specific advanced military technology to China was taken. For instance, China was able to acquire, in 2015, twenty-four advanced Russian fighter jets “Su-35,” six air defence systems “S-400,” and four “Lada-class submarines.” These acquisitions have allowed China to seriously alter the balance of power in the South and East China Seas and over Taiwan in particular. Not only that, Putin and Xi signed in 2015 a contract for jointly producing 200 next-generation heavy-lift helicopters by 2040. According to SIPRI, from 2016 to 2020, 77% of all Chinese arms imports, representing $5.1 billion, came from Russia, which amounted to 18% of Russia’s total arms exports. This is a 49% increase in arms sales compared to 2011-2016. China is Russia’s best client for arms sales, just behind India. One can wonder, however, if the poor military performance of Russia in Ukraine will not reduce its arms sales. The survivability and efficiency of Russian armoured vehicles, air defence systems, radar warning systems, and other military equipment have indeed been seriously compromised in Ukraine.

China also sells arms to Russia thanks to the rapid progression of its industrial-military complex, especially in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) technology, I.T. systems, and shipbuilding. For example, because of sanctions, Moscow cannot buy specific equipment from Western countries, such as diesel engines that it needs for its Buyan-M corvettes project. So, Moscow relies too on Chinese engines plus other electronic components to compensate for its non-access to Western military technology.

The Sino-Russian De facto Alliance, the War in Ukraine, and the World’s Bipolarization

From the 2000s to 2014, the Sino-Russian partnership gradually strengthened with an apparent acceleration starting in 2014 in all areas: political-diplomatic cooperation at the UN; economic complementarity; and defence cooperation based on geopolitical convergence. With the current war in Ukraine, there have been a lot of questions about the extent to which China would support Russia and if Beijing was aware of Moscow’s belligerent intentions. Given the depth of Sino-Russian military-to-military cooperation and Xi-Putin’s close personal relationship, it seems unlikely that China did not know that Russia was bent on attacking Ukraine. However, this does not mean that Beijing is willing to suffer full-effect secondary sanctions for Russia’s sake. Today, just like in 2014, China denounces the Western sanctions against Russia but simultaneously makes sure to comply with the sanction regime broadly. Beijing’s conundrum is that it cannot afford to completely sacrifice its economic exchanges and trade surpluses with the EU and the U.S., nor can it completely abandon its Russian partner. We’re seeing clear signs of prudence on China’s part: Beijing called for all parties involved exerting restraint in Ukraine; Chinese businesses have refused to provide airplane parts to Russia; and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the New Development Bank stopped working with Belarus and Russia to “safeguard their financial integrity.” Other Chinese banks like the Bank of China and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China reduced funds available to buy Russian commodities to comply with the sanction regime for fear of being cut off from the dollar. Huawei also rolled back some of its activities in Russia for that same reason. Not to mention China’s frustration with the disrupted global supply chains. Does it mean that Beijing will accept to fully isolate Russia because it does not want to suffer economic and reputational costs?

Russia’s Foreign Minister, Sergey Lavrov, visited Beijing on March 30th and met with his Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, on the margins of the Third Foreign Ministers’ Meeting on the Afghan Issue Among the Neighboring Countries of Afghanistan. This is a clear sign that China has no intention to turn its back on Russia when the West is increasingly pressuring Russia. Xi has already decided that he will not abandon Putin. As demonstrated throughout this analysis, China has invested a lot of resources and efforts in its relationship with Russia, whether in energy, technology, and defence. China has currency swap lines established with Russia allowing it to proceed with trade in its currencies, which lowers the risks of secondary sanctions. China has also politically oriented banks less connected to the dollar-based financial system and willing to provide Russia’s economic assistance. China has been doing it since 2014 and will keep doing it. China is suspected of having helped Russia stash dollar-denominated securities in offshore accounts in the Caymans and Belgium. If China is indeed creating a financial scheme to help Moscow access and hide liquidity ($77 billion in yuan reserves are in China), China will suffer repercussions. But Beijing is ready to accept some degree of economic pain for geostrategic reasons.

These geostrategic reasons consist in energy security and Taiwan. China is a net energy importer, meaning that it must secure such strategic imports to fuel its economic growth. Moscow is a reliable energy exporter that is eager to connect its gas and oil reserves to China through pipelines. Moscow is a strategic partner for China because it is linked to its energy security. And such energy security will increasingly become a central preoccupation of China’s foreign policy, given the intensification of the Sino-American contest in East Asia. As a matter of fact, Washington has been adding weight to its Indo-Pacific strategy (QUAD, AUKUS) and actively tries to mobilize its allies in the region to contain China. The U.S. is also very vocal about its willingness to guarantee Taiwan’s right to choose its destiny free of Chinese coercion. However, we know that Taiwan’s reunification with the mainland is non-negotiable and a matter of territorial integrity and honour from the Chinese point of view. Thus, Russia’s brute force method is something China could emulate against Taiwan if Beijing’s gray-zone measures fail to reunify Taiwan with the mainland. We also know that in the case of an attack on Taiwan, the U.S. would most likely implement a blockade against China on the Strait of Malacca, where 70% of Chinese petroleum and LNG imports depend. In such a scenario, Russia’s inland exports of commodities to China would become crucial as maritime routes would, in all likelihood, be blocked. So, as long as the Taiwan question is not settled, China will not abandon its Russian partner even if it implies economic and reputational costs. China needs Russia’s energy in the event of a war with Taiwan.

Russia is one of the few countries able to provide China with much-needed energy exports that it would need during turbulent times. If abandoned, Beijing would lose the benefits from Moscow’s military technology, which has a role in the modernization of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Depending on forecasts, the PLA will be able to lead a successful amphibious invasion of Taiwan by 2027 or 2049. In the meantime, China needs Russia’s military expertise. And if China invades Taiwan, securing Russian abstention on a potential UNSC resolution against China will also be crucial. Therefore, China has every incentive to support Russia in Ukraine while expecting Russia’s reciprocity in the case of a Chinese war against Taiwan – scratch my back; I’ll scratch yours. For these reasons, the Sino-Russian partnership will resist the current war in Ukraine and even strengthen, pushing further the bipolarization of the world.

Implications and Recommendations

The transatlantic unity has been robust in helping Ukraine and punishing Russia. It might not necessarily remain if the West has to sanction China because it would be a lot more painful to implement. Washington would struggle to get Europeans to significantly reduce trade with China unless the U.S. managed to compensate for the economic contraction that secondary sanctions would entail for the West. However, with the rise of protectionism in the U.S. and the increasing domestic polarization that impacts the stability of Washington’s foreign policy, it is unlikely that the U.S. could successfully do such a thing. The renewed transatlantic unity can quickly turn into transatlantic disunity. So, what should the West do about it?

The West should learn the lessons of the Ukrainian war not to replicate them over China. From 2015 to 2022, the West failed to give Putin hope that the Minsk II agreement could be implemented. In particular, Paris and Berlin did not pressure Kyiv in the Normandy Format to grant autonomy and amnesty to Donbas as they could have. This would have held Russian horses. One could also argue that if NATO had offered a Membership Action Plan to Ukraine in 2008, the current war might not exist. In any case, the West should give hope to Beijing that peaceful reunification with Taiwan is still possible, or at least that the status quo is safe, and that the One-China Policy still stands. At the same time, it is necessary to provide Taiwan with asymmetrical capabilities to increase the cost of a Chinese attack against the island. Joe Biden’s declaration explaining that the U.S. is ready to defend Taiwan militarily is counterproductive. As said above, Beijing knows its energy imports would be in jeopardy if a conflict over Taiwan breaks out because the maritime routes would most likely be closed off. Consequently, the current situation increases the value of Russia as a reliable energy, political, and defence partner for China.

However, China has tremendously benefited from globalization and does not want to revolutionize the international system but merely to legitimize its political regime and values on the world stage. A good part of the political-diplomatic dimension of the Sino-Russian partnership is based on a shared willingness to counter Western liberal meddling in their domestic affairs. Whether it is about human rights violations, democracy promotion, or outright calls to regime change, such Western interferences ultimately push China and Russia together. But, unlike Russia, China has interests in preserving the stability of the globalized economy. The more economic exchanges between the West and China, the more costly it is for China to damage its trading relations with Western countries for Russia’s sake. The U.S.-China decoupling would greatly reduce these costs.

If China and the U.S. could perceive one another not so much as ideological threats but as strategic competitors for structural reasons, then the basis of the ideological pillar of the Sino-Russian cooperation would erode. There is nothing the West can do to stop defence and energy cooperation between China and Russia, while it can certainly attenuate China’s fears about regime survival. And for that it is necessary to agree to disagree on ideology – neither will China liberalize nor the U.S. embrace one-party state capitalism. The only constructive way forward is to cooperate, when possible, while accepting competition when it is inevitable – which does not have to be about ideology. Thus, instead of rhetorically flexing its muscles, Washington should uphold its strategic ambiguity and accentuate the cooperation with China on business, climate change, nuclear proliferation, and pandemic prevention to balance a bilateral relationship defined by strategic competition. Doing that could induce China to hedge its bets a little more than it currently does.

Finally, looking at history, another way to put some distance in the China-Russia relationship relates to India. In the 1950s, a significant source of Sino-Soviet tensions was Russia’s closeness to India. The West should try to exacerbate this enduring Sino-Indian rivalry to fissure the Sino-Russian partnership. One way to do that involves arms sales. India is Moscow’s number one arm buyer, and both countries share a “special relationship,” while the Sino-Indian relationship is acrimonious. In 2018, India ordered $5 billion worth of Russian S-400 missile systems to deter China and Pakistan. India should receive most of the S-400s by 2023. If Moscow delivers the S-400s to India, as it intends to do, this will inevitably trigger Chinese ire. Beijing does not want the balance of power vis-à-vis New Delhi negatively altered because of its “Russian unlimited partner” arming its regional rival, India. On the other hand, if Washington tries to prevent India from getting these S-400s through the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, it could cut short Chinese grievances against Russia. Therefore, the U.S. could turn a blind eye to the deal in order to sow Sino-Russian discord by exploiting power dynamics. Moreover, the S-400 will be aimed at China and Pakistan and hence does not threaten Washington or its allies. If conditions arise, this methodology can be applied to Vietnam and other countries which share a close relationship with Russia and are under serious pressure from China.

***

The Sino-Russian partnership has strengthened since the 2000s with a clear acceleration after Crimea’s annexation in 2014. It is based on three pillars: political-diplomatic cooperation, defence cooperation, and economic complementarity. China did not abandon Russia in 2008 nor 2014 and will not abandon Russia in its Ukrainian war today. Russia plays a role in one of Beijing’s most important foreign policy objectives: energetic security. In the case of war for Taiwan, China would greatly rely on Russian inland commodities exports as the U.S. would most likely bloc the Strait of Malacca, where most Chinese sea energy imports transit. Despite China’s dazzling military progression, China still needs Russia’s military technology to modernize the PLA to be capable of leading a successful invasion of Taiwan. Beijing will also need Russia’s diplomatic abstention at the UN if war breaks out over Taiwan. Therefore, as the West is sanctioning and isolating Russia, China will remain a reliable partner of Russia. Beijing will not use its leverage over Russia to stop the war. China’s position will increasingly irritate the West, and the bipolarization of the system will deepen, even more so if secondary sanctions are imposed on China. To drive a wedge between China and Russia it is necessary to 1) temper ideological rhetoric aimed at China; 2) balance the inherent tensions of the Sino-American rivalry through cooperation on climate change, nuclear proliferation and pandemic prevention; 3) reaffirm the One-China Policy; 4) use power dynamics to exacerbate Sino-Russian contradictions; and 5) incentivize China to favor its economic exchanges with the West relative to its strategic partnership with Russia.

Comments are closed.