|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The Russian invasion of Ukraine sent such a shock wave through Western capitals that it led to a military surge. This is marked, among other things, by massive reinvestments in defence budgets, the deployment of thousands of troops to NATO’s eastern borders, the accelerated and substantial delivery of weapons to the Ukrainians, a consensus on the clear and immediate threat posed by Russian revanchism, and an expansion of NATO to include Sweden and Finland. In short, the Atlantic Alliance appears resurrected after its so-called “brain death” announced in the fall of 2019.

To this portrait of unity, however, it must be acknowledged that some disparity remains in the allies’ surge on two levels. First, allies vary in their level of defence reinvestment and in the extent of support for Ukraine. President Zelensky sees this as a result of their differing interests. He was critical of the French, who refuse to provide offensive weapons “because they are afraid of Russia,” and of the Germans, who “are making a mistake” in wanting to preserve their economic ties with Russia.

The allies also differ on the desired outcome of the war. The United States and the United Kingdom share Ukraine’s maximalist position: the total defeat of Russia. According to the U.S. Secretary of Defense, “Ukraine can still win the war” by permanently weakening Russia to the point where it cannot invade its neighbors. Similarly, the British Foreign Secretary argues that Ukraine’s victory – a “strategic imperative” – requires “to push Russia out of the whole of Ukraine” and providing it with NATO-standard defensive and offensive weapons.

In contrast, France, Germany and Italy, in particular, remain faithful to the initial objectives of the war, i.e., to minimize Ukraine’s territorial losses and force Russia to negotiate a cease-fire that is as favorable as possible to Ukraine. In the words of President Macron: “We remain focused on our objective: to do everything to obtain a ceasefire and help Ukraine negotiate on the terms that Ukraine will decide for itself.” The German chancellor also believes it is imperative to end the war as soon as possible. While both sides agree that they support Ukraine’s territorial integrity and that it is up to the Ukrainians to determine the acceptable terms of a negotiated settlement, the maximalists have an interest in prolonging the war to inflict lasting losses on Russia. The minimalists, in turn, favour a rapid resolution of the conflict and a peace agreement that is “neither in denial, nor in exclusion of one another, nor even in humiliation.”

What about Canada? If the rhetoric coming out of Ottawa is anything to go by, it is firmly in the maximalist camp. Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland went so far as to call for a regime change in Moscow: “The world’s democracies—including our own—can be safe only once the Russian tyrant and his armies are entirely vanquished.” During his visit to Kyiv, Prime Minister Trudeau also called for a Ukrainian victory over Russia.

The problem is that, true to form, the Canadian government is easy on the rhetoric and soft on the action. It is acting in contradiction with the advice of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt: Canada speaks loudly but holds a small stick. This paradox is illustrated in terms of defence investments, troop deployments to Europe and the provision of arms to Ukraine. This gap between words and deeds is not new, but it undermines Canada’s ability to articulate a coherent defence policy. If it is in Canada’s interest for Ukraine to inflict a total defeat on Russia, why not provide more military support to Ukraine? It seems that Ottawa prefers grandiloquent rhetoric at lower cost, which translates into a cheap liberal internationalist posture. It would be better to focus on better defining the contours of the desired peace and to mobilize all energies to achieve it.

Modest Defence Reinvestment

While delivering a fiery speech calling for the defeat of “the Russian tyrant,” Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland announced a modest additional investment of $8 billion over five years. The vast majority of this amount, $6.1 billion, will be used to modernize the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and to fund Canada’s contribution to NATO. $500 million has been budgeted for direct assistance to Ukraine. The dispersal of funds over time suggests that the Canadian government is not in a position to quickly replenish its military budget. Indeed, the annual breakdown of the $6.1 billion will go from $100 million in 2022-23 to $1.875 billion in 2026-27.

As the Canadian government’s budget projections illustrate, the new expenditures have been on an upward trend since the Trudeau government took office in 2015. Defence spending is set to double between 2016-17 and 2026-27. However, the largest increases are also the furthest away. Given the rampant inflation – over 7% in 2021 – and the inability of the Department of National Defence to fully spend its annual budget (almost $10 billion was not spent between 2017 and 2021), the increase in Canada’s military budget may be much smaller than projections suggest. According to the Parliamentary Budget Officer, military spending is expected to increase to a peak in 2027-28 and then fall back sharply. Given rising inflation, spreading the projected cost over time may reduce the purchasing power of these increases, requiring new investments to acquire the desired equipment.

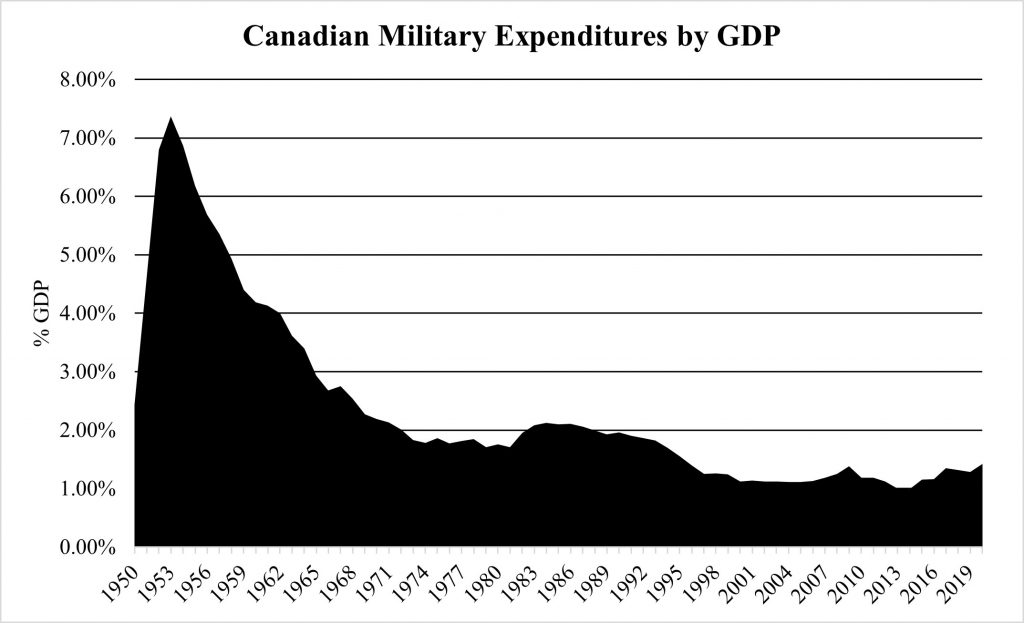

The budget increases announced with great fanfare by Minister Freeland will not allow Canada to reach the NATO target of 2% of GDP. Canada would have had to invest an additional $16 billion per year to reach such a target – 10 times more than planned. Without additional investment, Canada’s defence spending as a share of GDP will not exceed 1.5% in the coming years. This contradicts the commitment made at the 2014 NATO Wales Summit, where all allies agreed to seek “to move towards the recommended 2% over the next ten years.” While the Minister of Defence once hinted that Canada might meet or even exceed the 2% threshold, this is no longer being considered. This under-investment, which has been evident since the end of the Cold War, has long irritated the United States, which has criticized Canada for not paying its fair share of the defence burden. Canada ranks 25th among the 30 NATO allies in terms of military spending relative to its gross domestic product.

While the 2% target may seem arbitrary, the same cannot be said for the target of investing in defence in line with national needs. Canada is equally poor on this score. The 2017 defence policy did not include a budget for the modernization of the North Warning System (NWS), a chain of radars along the Arctic Ocean to monitor airspace, which the former NORAD commander said was becoming obsolete. While modernizing the NWS could cost Canada as much as $6 billion, the 2022 budget provides only $252 million in funding over five years to “lay the groundwork” for modernizing the defence of the North American continent. Details of a “robust” package of investments for North American defence are expected in the coming months, including the construction of an arctic over-the-horizon radar in 2028, estimated to be worth over $1 billion. While the Minister of National Defence acknowledges that Canada faces a “less secure, less predictable and more chaotic” security environment, she promises to deliver a “bold and aggressive” approach to the defence of the North American continent later.

Furthermore, the Trudeau government has been silent on how much of the reinvestment will go to NATO. Does this include the decision to acquire 88 F-35 fighter jets, 23 more than planned, to simultaneously contribute up to 36 fighter jets for NORAD and a squadron to NATO air patrols? Or does Ottawa intend to increase the capabilities of its three mechanized brigade groups, including the one on alert for NATO’s Response Force, first activated in response to the invasion of Ukraine? No details have been released since the budget announcement, leaving the nature of the reinvestments in doubt. Given the discussions at NATO regarding the reinforcement of military contingents in Eastern Europe, which could result in the pre-positioning of troops on a permanent basis, it is unclear whether Canada is anticipating the costs that this could represent.

Military Deployments in Decline

Canada’s usual response to critics who accuse it of under-investing in defence is to focus on the country’s actual contributions to allied operations. In the words of Prime Minister Trudeau: “At the end of the day, the most important parameters are always: are countries building the capabilities that NATO needs? Are we able to provide different resources and demonstrate the kind of commitment to the Alliance that needs to always be there?” On that level, Trudeau believes “Canada can be extremely proud.”

It is true that Canada is one of the allies commanding a NATO battle group as part of its enhanced forward presence mission in Eastern Europe. Canada has led the NATO battalion in Latvia since June 2017, following the Atlantic Alliance’s decision to enhance its military presence in the region in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea. This NATO presence was further strengthened following the invasion of Ukraine, with the deployment of additional multinational battle groups to Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia. The Alliance also deployed additional ships and aircraft to increase its deterrence and defence posture against Russia.

In this context, Canada announced on February 22, 2022, the deployment of an M777 artillery battery and an electronic warfare troop, composed of about 165 soldiers, bringing to 695 the Canadian military contingent in the battalion it commands. In addition, a second frigate is stationed in Europe to augment the one that is deployed there virtually year-round. Given that Canada has only five to six operational frigates, this contribution raises concerns about the capability limits of the Canadian Navy. Canada has also reassigned a CP-140 Aurora long-range patrol aircraft from Iceland to augment NATO forces in the Euro-Atlantic region. While six CF-18 Hornet fighter jets have been deployed to Eastern Europe six times since 2014, the last deployment was in the fall of 2021; no deployment has been announced following the invasion of Ukraine.

As commendable as these additional deployments are, they fall short of those of other NATO framework nations, even at the ground force level. The United Kingdom, which commands the battle group in Estonia, has doubled the size of its contingent – from 900 to 1,750 troops – and deployed more tanks and armored vehicles. The U.S., leading the battalion in Poland, has increased its presence by an additional 4,700 troops, as well as expanding its presence in Germany, Lithuania and Bulgaria, bringing the number of U.S. troops in Europe from 80,000 to 100,000 since the Russian invasion began. France has deployed 500 troops to Romania, including armored vehicles, to command a new battle group there, along with 300 Belgian troops. Germany deployed an additional 350 troops to the 550 stationed in Lithuania, including an air defence system and artillery units, to augment its contingent leading the battle group in that country. Moreover, Canada’s additional contribution in Latvia is less than that of other allies under its command, including an additional 250 Italian troops and more than 800 Danish soldiers as reinforcements.

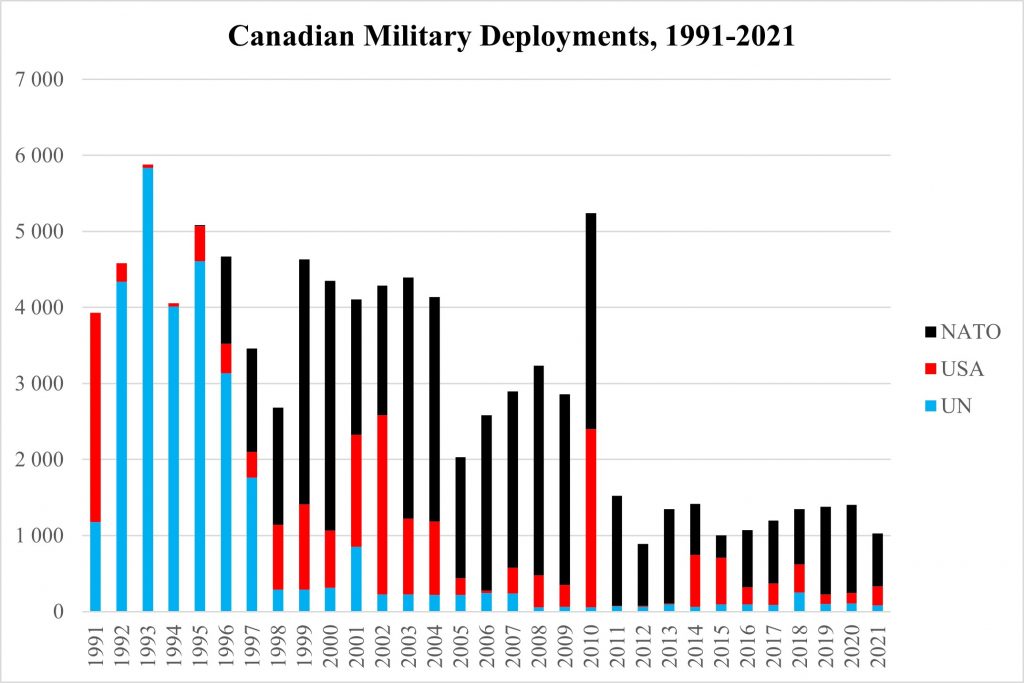

These figures demonstrate that Canada’s reputation as a free-rider in the Atlantic Alliance is not unfounded. For those who might think that Canada’s small contribution in Eastern Europe is anecdotal, the data collected by Scott Cooper and Kendall Stiles shows that it is symptomatic of a larger trend. On a per capita basis, Canada’s military deployments to NATO “out-of-area” operations are below the average of other NATO members. Canada ranks 19th in terms of military contributions relative to population between 2004 and 2018.

Some may be tempted to believe that Canada is choosing instead to focus its military contributions to international security in other types of operations. After all, shortly after taking office, Prime Minister Trudeau declared that Canada was “back” on the world stage, particularly through UN peace operations. However, of the 600 peacekeepers and 150 police officers promised, only a maximum of 167 military and 89 police officers were actually deployed in 2019 and 2015 respectively. This under-contribution continues a clear trend since the early 2010s: a net decrease in Canadian military deployments abroad, regardless of the type of mission. For example, since the end of its combat mission in Afghanistan in 2010, Canada has deployed just over 1,200 military personnel abroad on an annual basis, compared to nearly 4,000 between 1991 and 2010.[i]

Significant Military Support to Ukraine

The picture is brighter when one looks at Canada’s direct contribution to Ukraine. Canada was one of the few allies to deploy troops to Ukraine after the annexation of Crimea to help train its military. Given the battlefield success of the Ukrainian military, the 200 or so Canadians who have trained more than 33,000 members of Ukraine’s Security Forces since 2015 – including nearly 2,000 members of the Ukrainian National Guard, have much to be proud of. They are partly responsible for the Ukrainian military’s unheralded successes against the Russian invader, which relies on, among other things, the tactical skills, combat training and professionalization of the Ukrainian Armed Forces developed since 2015. These capabilities could have been even greater, were it not for the misleading intelligence assessment, which overwhelmingly underestimated the Ukrainians’ willingness to fight and overestimated the advantages of Russian military superiority. If these intel reports had been more accurate, military support from the U.S., U.K. and Canada might have been greater.

That said, the allies limited their support for Ukraine after the annexation of Crimea so as not to provoke Russia into further invasion of Ukraine. Not to be outdone, Canada has long limited its material aid to non-lethal military equipment, including flak jackets, night vision equipment, helmets and gas masks. It was not until February 14, 2022, that it agreed to provide the weapons requested by Kyiv. At that time, Ottawa announced that it would join the United States, the United Kingdom, Poland, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, and Lithuania in supplying arms to Ukraine. However, these were limited to small caliber weapons, including pistols, machine guns and sniper rifles.

It was not until the February 24 invasion that Ottawa agreed to supply Ukraine with larger calibre weapons. The Trudeau government first increased the delivery of non-lethal equipment, including night-vision goggles, and on February 28 offered 100 Carl Gustav anti-tank weapons systems and 2,000 rockets. Three days later, Ottawa added 4,500 M-72 rocket launchers and 7,500 grenades. These weapons were welcomed by Kyiv but judged insufficient. The Ukrainian president asked for heavy artillery, tanks, air defence systems, armoured vehicles, helicopters, fighter planes and missiles. However, the Minister of National Defence says that Canada has “exhausted” its weapons inventory and that the Canadian Forces are facing “capacity problems.” This startled many, including former Chief of Staff Rick Hillier, who suggested that Canada deliver 250 of its upgraded light armoured vehicles. But government sources explain Canada’s reluctance because of the need for training and spare parts for Ukrainian forces. Others suggest that Canada provide Harpoon anti-ship missiles, 120 of which are stored by the Royal Canadian Navy, to help the Ukrainians defend Odessa against a Russian assault. Government sources say the U.S. is opposed to this, which U.S. officials deny.

After weeks of international and political pressure, the Trudeau government announced on April 18 the delivery of heavy artillery, four M777 howitzers among the 30 batteries acquired from the United States in 2005, as well as training on these systems in a country bordering Ukraine. In addition, eight armored vehicles, cameras for unmanned aerial vehicles, and satellite imagery have been supplied to date. During his visit to Kyiv, Prime Minister Trudeau stated that Canada would continue to do “whatever is necessary” to support Ukraine, which pleased President Zelensky, who in turn stated that he could not ask for more than to put pressure on other allies, since Canada had already provided him with “everything he had.”

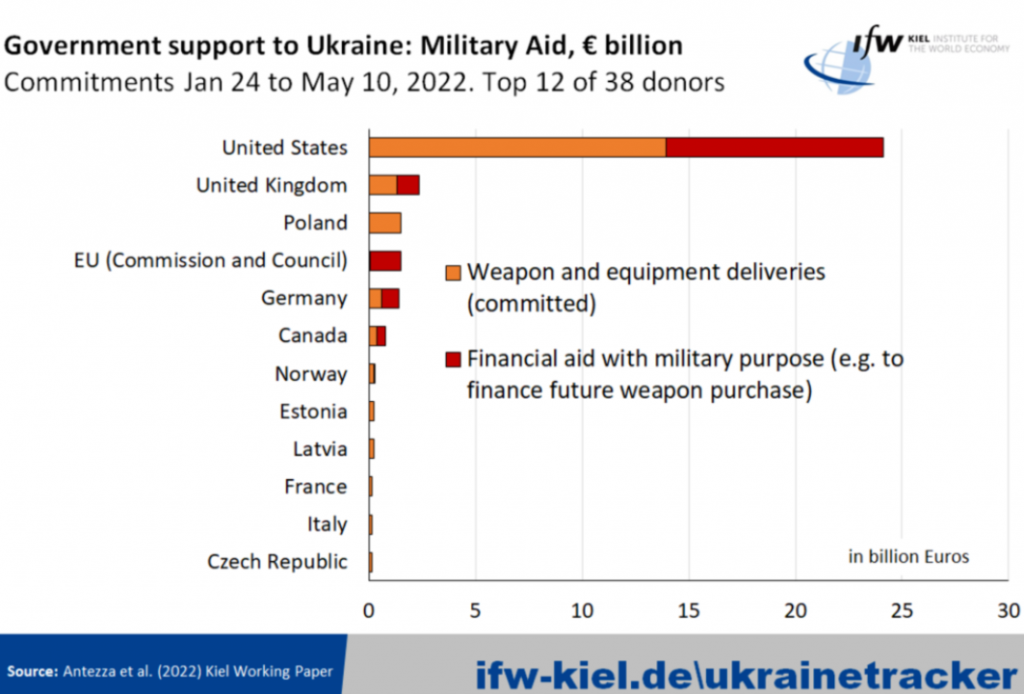

According to data compiled by the Kiel Institute, Canada is the sixth largest national provider of assistance to Ukraine since January 24, 2022, with a total support of 2 billion euros. This is considerably less than the United States, which has offered close to €43 billion — about three times the assistance offered by all European countries and institutions (nearly €16 billion), or the United Kingdom (€4.8 billion), Poland (€2.6 billion), Germany (€2.3 billion), and France (€2.1 billion), but far ahead of Italy (€0.48 billion) and other Western states. In terms of GDP, Canada is the 10th largest donor, this time also outpaced by the Baltic States, Slovakia, and Hungary, but ahead of Germany.

Canada moves up the rankings in terms of the main commodity requested by President Zelensky, the provision of weapons, with total support of 0.76 billion euros. This is still well below the €24 billion committed by the United States, but nearly five times more than the support offered by France (€0.16 billion) or Italy (€0.15 billion).

Finally, in terms of heavy weapons, which could enable Ukrainian forces not only to repel the Russian assault in the Donbass, but possibly to recapture lost territory, the Canadian commitment pales in comparison to that of its allies. Canada’s main contribution is the delivery of four M777 howitzers, which is less than the amount of heavy artillery units offered by the United States (90), the Czech Republic (20), France (12), Estonia (9), Germany (7), Australia (6), and the Netherlands (5), according to data collected by the Kiel Institute. Unlike many, Canada has not offered tanks, man-portable air defence systems, or drones, heavy weapons that are crucial to the battle in Donbass.

Thus, while Canada is offering significant support to Kyiv in the war against Russia, its assistance does not commensurate with its posture in favour of a total victory for Ukraine. Contrary to the desire of the Minister of Defence, Canada does not appear to be “ready for a potentially more dangerous phase of this war,” i.e., to offer the weapons necessary for Ukraine to attempt to regain control of its territorial sovereignty.

Atlanticism at a Lower Cost

What does Canada seek with its Ukrainian policy? Officially, Canada aspires to the withdrawal of all Russian military forces and their “proxy agents” from the entire territory of Ukraine. This has been the case since the annexation of Crimea, as evidenced by the famous statement of then Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper during an unannounced meeting with President Vladimir Putin at a G20 summit: “I guess I will shake your hand but you need to get out of Ukraine.” Of course, not only did Russia not pull out of Ukraine, it chose instead to attack it again in an even more brutal manner.

So, is Canada’s Ukraine policy just a sham? One could certainly think so, given the imposing size of the Ukrainian diaspora in the country – the second largest in the world after Russia, with 1.4 million nationals of Ukrainian origin, or 3.8% of the Canadian population. Its electoral weight is particularly concentrated in the three Canadian Prairie provinces (Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba), where it represents 11% of the population. All the main political parties are therefore courting the Ukrainian diaspora vote by adopting strong positions. One might therefore have expected the Trudeau government to accede to the repeated demands of the Ukrainian Canadian Congress to do more, including providing the heavy weapons that Ukraine has long been asking for.

The gap between rhetoric and action with respect to Ukraine is explained by Canada’s Atlanticist strategic culture, that is, its predisposition to support the Atlantic Alliance in order to avoid Canada’s international marginalization, but at a lower cost. Canada has supported every major NATO initiative since its inception and has actively sought to resolve the differences that have divided its major allies over the past decades. However, this commitment is made with a view to minimizing costs to Canada. Canada’s strategy for defending itself on the international stage is to brandish the Maple Leaf, that is, to ensure a visible Canadian presence, without seeking to achieve any strategic goals other than avoiding marginalization. In other words, Canada sees its military contribution in Ukraine as evidence of the success of its strategy, rather than a mismatch between political objectives and military means.

There are several inconsistencies that flow from this Atlanticism at the expense of the United States. While Canada lobbied with the United States for Ukraine’s “full membership in the alliance” at the 2008 NATO summit in Bucharest, it has so far refused to offer the security guarantees desired by President Zelensky in exchange for Ukraine’s renunciation of NATO membership. Similarly, Canada has declined to offer direct security guarantees to Sweden and Finland until they join NATO, despite its unqualified support for their candidacy. Finally, Canada favours a multi-role defence posture that allows its military to operate in multiple roles, but on a temporary and marginal basis, rather than focusing its limited resources on specific advanced capabilities. It therefore has several weapon systems, but not in sufficient quantity to contribute with impact to a long-term proxy war. This sampling does not allow for the volumes of armaments needed for sustained high-intensity warfare.

Conclusion

Canada’s military awakening is not for tomorrow. The main obstacle to reversing its reactive and minimalist posture lies in an invariant that is not likely to disappear any time soon: the U.S. involuntary security guarantee towards Canada. Regardless of its public positions, Canada does not have to invest significantly in its defence, since the United States protects it against foreign aggressors. It must only contribute enough to maintain a certain international visibility and satisfy its domestic public. Canada can thus call for the overthrow of President Putin while refusing to supply the weapons necessary for Ukraine to defeat its aggressor. It can also want Russia to respect Ukraine’s sovereignty, while refusing to enter into dialogue with its president. This disconnects Canada’s desired outcome from the war in Ukraine from the efforts required to achieve it.

The main consequence of Canada’s posture lies in the deprivation of international influence and the absence of strategic anticipation. By refusing to “pay its dues” and clearly articulate its interests, Canada is at best uninfluential and at worst marginalized. In the context of the war in Ukraine, this translates into a lack of weight on a possible end to the war. Given that a partition of Ukrainian territory is more than likely, and that a revanchist Russia is here to stay, Canada should focus its attention on these scenarios and mobilize its resources for medium- and long-term protection of Ukraine. In other words, Canada needs to think and act strategically rather than make sweeping statements while wallowing in the comfort of its North American security.

[i] Military Balance, International Institute for Strategic Studies. Data compiled by the author.

The original version of this text was published in French on Le Rubicon. Check it out here!

Comments are closed.