|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

This policy report is part of a special series, directed by Laurent Borzillo (Forum de défense et stratégie, FDS), Teodora Morosanu (FDS), and Benjamin Boutin (Association France-Canada) with support from the Canadian Department of National Defence’s Mobilizing New Ideas in Defence and Security (MINDS) program and the DGRIS (Directorate General for International Relations and Strategy) of the French Ministry of the Armed Forces, which aims to develop Franco-Canadian strategic exchanges.

Summary

This policy report highlights the importance of conflict sensitivity in France-Canada climate adaptation initiatives, particularly in fragile contexts. These initiatives should not only respond to climate challenges, but also foster social cohesion and community resilience. This analysis synthesizes perspectives gathered from interviews with experts in the field. These experts emphasize both the importance of empowering local players and the challenges of implementing a conflict-sensitive approach. Thus, this analysis supports the idea that French and Canadian climate adaptation initiatives in fragile contexts should include gender analysis and social inclusion (GESI), prioritize local leadership and participatory methods, to develop effective and sustainable adaptation measures. Here are the key recommendations of this analysis:

- It is essential that climate change adaptation interventions do not aggravate existing social tensions. A thorough contextual analysis and a “Do No Harm” approach must be put in place to avoid exacerbating conflicts. In particular, projects must be designed to be sensitive to local dynamics, including gender and social inclusion analyses (GESI), and participatory methods to ensure that marginalized voices are taken into account.

- Involving local communities right from the project design phases would ensure that solutions are adapted and truly relevant to local contexts.

- Local capacity-building and conflict sensitivity training could ensure the sustainability of adaptation projects. Local teams, as well as French and Canadian partners, need to be trained to better understand conflict-sensitive approaches and develop adapted solutions.

Finally, to ensure the effectiveness of climate adaptation interventions in fragile contexts, it is recommended to organize an annual consultation between Canadian and French institutions, as well as local ministries and actors. This participatory process is particularly relevant in these contexts, as it would not only help coordinate efforts between local, national and international players, but also ensure that interventions take into account local realities and dynamics. This ongoing dialogue would also promote the inclusion of local communities in decision-making, thereby strengthening collective resilience to the impacts of climate change in fragile contexts.

Context

According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), climate security refers to the impacts of the climate crisis on peace and security, particularly in fragile and conflict-affected contexts. Considered a crisis multiplier, and a threat to national, human, international and ecological security, climate change is likely to exacerbate the risks that already threaten peace and security, especially in countries in fragile situations. Although climate change is not a major cause of large-scale armed conflict, it could aggravate and prolong existing conflicts, and exacerbate existing vulnerabilities in already unstable regions. Indeed, population movements, environmental pressures such as floods, droughts and extreme weather events caused by climate change could exacerbate competition for resources, political instability in fragile states and potentially mass migration flows.

For countries already beset by multiple crises or conflicts, climate change could further exacerbate social tensions, increase people’s vulnerability and grievances, and reduce economic opportunities. Overall, Africa and Asia are likely to be the most vulnerable regions in terms of humanitarian consequences. For example, in SPARC‘s report on perceptions of cross-border climate change risks and adaptation, survey participants from East and West Africa highlighted that:

Droughts and floods are among the most serious climate change-related risks facing their regions. Land degradation and biodiversity loss are constant challenges across the Sahel, impacting livelihoods, water resources and human and animal health.

As a result, climate security, a subject of growing concern in recent years, remains an issue of prime importance within regional and international organizations such as the Security Council, the African Union Commission, the European Union and NATO. In addition to threat assessment, climate security includes the ability to meet climate-related challenges. It has an adaptive dimension, as it implies not only resistance to risks, but also the ability to adapt and find solutions to the impacts of climate change.

Emphasizing Conflict Sensitivity in Climate Adaptation

The first Franco-Canadian partnership for climate and the environment was signed in 2018 and renewed in 2021. The third edition of the partnership has now been adopted for a three-year period (2024-2027). In addition to the partnership between the Government of the French Republic and the Government of Canada for Climate and Environment – 2024-2027, France and Ca-nada are also involved in climate issues affecting many countries in the South, and collaborate with these countries (researchers, governments, experts, etc.) on initiatives aimed at strengthening climate resilience. Their involvement as world leaders in climate action is based on their strategic interests, humanitarian commitment and international development efforts.

However, to respond effectively to the impacts of climate change, it is not enough to tackle climate challenges alone. It is essential to ensure that adaptation interventions do not exacerbate existing social and political tensions. In particular, we need to ensure that humanitarian and development interventions do not exacerbate conflict, especially in fragile situations. Indeed, climate change adaptation strategies, particularly those relating to natural resource management, can lead to increased insecurity of land rights, marginalize minority groups, and accelerate environmental degradation. Above all, both local and international institutions could reduce or exacerbate the likelihood of conflict, depending on how initiatives are administered. They could affect the distribution of services; response capacity and the way disputes are managed.

Thus, a conflict-sensitive approach defined as an organization’s ability to understand the context in which it operates considers certain factors to be effective: public consultation, transparency and consideration of marginalized voices in project planning and implementation. This approach also refers to the concept of “Do No Harm”, “which mandates that organizations take steps to prevent and mitigate the potential negative consequences of their actions on affected populations”.

This concern also seems to be shared by France and Canada, which are actively engaged in various climate efforts, notably through initiatives such as CLARE (Adaptation aux changements climatiques et résilience), spearheaded by the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) and the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), as well as programs such as ADAPTACTION by the Agence Française de Dévelopment.

In addition, a conflict-sensitive approach is also relevant to the design and implementation of climate adaptation initiatives in contexts that are not necessarily classified as fragile states or conflict zones. Indeed, many regions may face underlying social, economic, or political tensions, even in the absence of open conflict.

Integrating a conflict-sensitive approach into climate adaptation interventions

1. Contextual understanding and analysis of gender equality and social inclusion (GESI)

The design of climate adaptation projects must take into account the experiences of different groups in dealing with conflict and climate change. A project that ignores conflict or works in isolation from active conflict is unlikely to succeed. Instead, adaptation projects should draw comparisons and parallels between the ways in which different groups experience vulnerability to climate change and conflict, using this understanding to design interventions that are sensitive to these dynamics.

Understanding context through intersectional analysis helps to identify key players and give a voice to marginalized populations, rather than allowing dominant voices to prevail. A GESI analysis would not only reduce the risk of exacerbating conflicts, but could also help researchers to acknowledge their subjectivity, thus ensuring that adaptation interventions are designed with sensitivity to local socio-political dynamics. Most importantly, these analyses are also aligned with the United Nations’ Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda, which guides gender aspects in development interventions. This agenda emphasizes the importance of involving women and marginalized groups in peace and security processes, ensuring that their perspectives are integrated into conflict prevention and peace-building efforts.

2. The importance of local leadership and ownership

Implementing a conflict-sensitive approach would prevent external researchers from parachuting into local contexts. This approach is essential to avoid harm and to ensure that adaptation interventions are truly representative of the local context. For research projects, it is therefore essential to have a good understanding of the context in which we intervene. Who are the key players, and how can they be effectively involved? Above all, experts advocate empowering these players. The first step is therefore to work with local partners, while ensuring that this partnership is equitable, by making sure that they really do have the necessary power to direct the project implementation process. It is important to involve stakeholders and communities in the initial phases of the project, ensuring that this period is used to engage stakeholders and communities, so that researchers have time to revise their objectives, questions and methods if necessary.

The Case of South Sudan

South Sudan perfectly illustrates the importance of adopting a conflict-sensitive approach to adaptation measures, but also the challenges this represents. Climate change has caused Kapoeta pastoralists to alter their migration patterns, encroaching on land traditionally belonging to other ethnic communities, or crossing the migration routes of other pastoralist groups, intensifying tensions due to increased pressure on resources. In their article entitled “Conflict-sensitive aid at the intersection of climate change, conflict and vulnerability in South Sudan”, Pech and Chan focus on recent research carried out by the Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility (CSRF), focusing on two case studies: Kapoeta, in Eastern Equatoria State, and the Mangala-Bor corridor. The aim was to identify and reflect the views of South Sudanese communities affected by both climate change and conflict, and their interaction with the aid system.

Indeed, in the Mangala-Bor corridor, floods have often coincided with periods of intense political violence.

Map of South Sudan (ministry of Foreign and European Affairs, 2011)

Map of South Sudan (ministry of Foreign and European Affairs, 2011)

But above all, gender is also a considerable dimension in this nexus of cli-matic change, conflict and displacement. As Pech and Chan point out:

As the main providers of food and water, and with fewer livelihood options when displaced, due to generally lower literacy rates and a more fragile social and economic position, women are particularly vulnerable to the increasing scarcity of clean water and food. In some cases, they are forced to undertake risky activities, such as traveling longer distances to access water or selling alcohol, which exposes them to sexual and gender-based violence. At the same time, this intersection also affects men and boys, notably by linking masculinity to cattle-raising, which exposes them more to forms of organized violence.

It is therefore clear that a conflict-sensitive approach in such complex contexts would be essential in any climate change adaptation strategy. However, humanitarian actors face complex conflict-sensitivity challenges for a variety of reasons, including community perceptions of aid agencies, criticism of aid responses perceived as “inadequate” and “poorly targeted”. But above all, other issues make it difficult to implement a conflict-sensitive approach, such as “limited resources”, the increasing pressure that aid actors may feel, and above all, the “lack of capacity or expertise to support integrated, climate- and conflict-sensitive action”.

This should not, however, discourage efforts to adopt a conflict-sensitive approach, nor lead to abandonment in the face of difficult contexts. Thus, according to Pech and Chan, aid initiatives should:

- Consider the context in which actors operate.

- Promote strategies that ensure assistance is contextually relevant and co-designed with communities.

- Consider the potential impact of the construction of dikes and other flood management infrastructures on migration routes.

- Integrate conflict management systems into water, sanitation, and hygiene projects such as boreholes, hafirs and dams.

Above all, to be effective, a conflict-sensitive approach should also consider a peace perspective, i.e., promote sustainable resource management, but above all foster dialogue between conflicting parties.

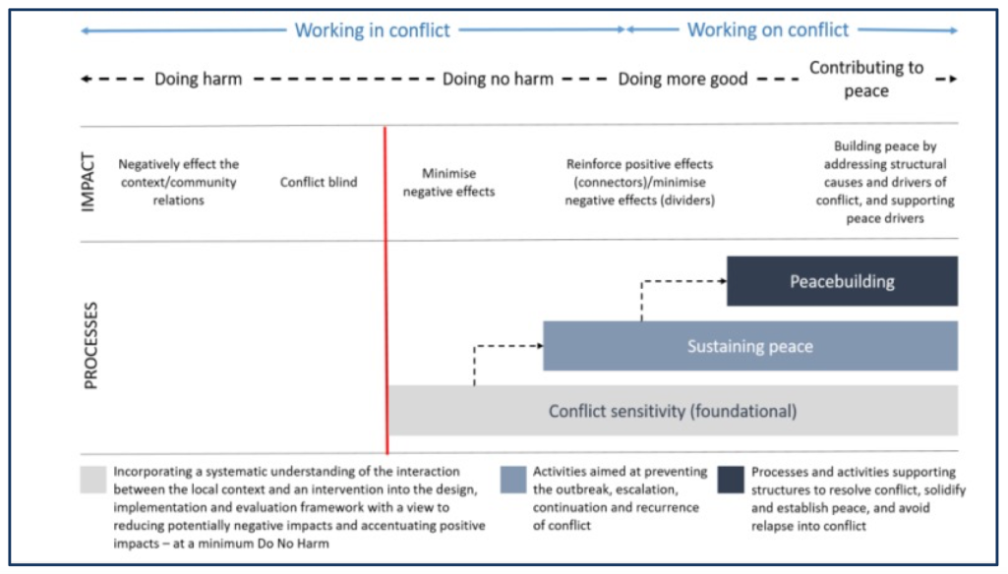

These recommendations are complemented by the tool presented in Pech and Chan’s study, taken from the UNHCR learning document on South Sudan. While this model illustrates how interventions can, in worst-case scenarios, cause unintended damage to communities and community relations, it also emphasizes approaches that minimize such damage, but above all those that positively address the causes and drivers of conflict.

Conflict sensitivity model: the Peace Spectrum[1]

Conflict sensitivity model: the Peace Spectrum[1]

The Role of Participatory Methods

Current best practice in adaptation – whether in research, development or humanitarian aid – tends to be participatory, focusing on the inclusion of different groups through a variety of tools, including living labs. Participatory methods, such as those used in living labs, are essential to foster inclusion and enable vulnerable communities to express their needs in a controlled environment. These methods not only facilitate dialogue and conflict resolution, but also enable experimentation with collaborative approaches.

However, it is important to note that participatory methods explored in the context of adaptation can sometimes make conflicts more visible. This is not necessarily negative, especially when these conflicts involve institutions or groups with different social or economic statuses. These discussions and this transparency offer marginalized or disadvantaged groups the opportunity to make their voices heard, which could help to correct injustices and ensure greater equity in the management, governance and redistribution of natural resources.

Ensuring the Sustainability and Positive Impact of Interventions

To ensure that climate adaptation interventions are both sustainable and beneficial, it is imperative to adopt a holistic approach that integrates climate security and conflict sensitivity. France and Canada, as key players in this field, have a crucial role to play in implementing strategies that respond to local needs while avoiding aggravating existing tensions. Here are the essential elements that could help achieve this objective:

1. The importance of participatory diagnosis

A thorough diagnosis is essential to understand local dynamics and avoid the undesirable effects of interventions, including maladaptation, i.e. interventions that exacerbate tensions and conflicts instead of alleviating them. This diagnosis must be participatory, involving local populations in the collection and analysis of information. This approach not only provides an accurate picture of needs and vulnerabilities, but also ensures that interventions do not harm communities. It is crucial to establish mechanisms for continuous feedback and open communication with local stakeholders to enable projects to be adapted and improved on an ongoing basis.

Participatory monitoring and evaluation mechanisms are essential to ensure that interventions achieve their objectives without unwanted side-effects. By actively involving local communities and stakeholders, these mechanisms enable potential problems to be detected and corrected quickly, while ensuring that interventions remain adapted to changing community needs.

2. Capacity building and training

Building local capacity is fundamental to ensuring the sustainability of interventions. Projects must include training and modules to help local players understand the challenges of climate security and apply the skills needed to tackle them. French and Canadian teams working closely with local players must also follow these training courses. Initiatives supported by France and Canada can support workshops, courses and training to strengthen understanding of climate and conflict management issues, while collaborating with local stakeholders to ensure that interventions are adapted to the specific context. French-Canadian initiatives could support conflict sensitivity in training programs for local actors, and for Canadian and French teams involved in research projects, which would include modules on conflict management, peaceful dispute resolution, and inclusion of the perspectives of marginalized groups.

3. Consultation and collaboration with stakeholders

Interventions must be designed in close collaboration with local stakeholders, including governments, NGOs, and communities. It is crucial to consult these stakeholders from the planning and implementation phases to ensure that projects meet local needs and respect cultural and political norms. Projects must include mechanisms to secure stakeholder approval and ensure that interventions do not reinforce existing tensions. Cross-sector collaboration, including mobilizing diplomatic networks and capacities in international development and conflict management, is essential to developing solutions to the challenges posed by climate change in fragile contexts.

4. Promoting social cohesion and avoiding maladaptation

Finally, it is crucial to recognize that climate security and conflict sensitivity are intrinsically linked to the promotion of peace and social cohesion. Climate interventions must not only mitigate environmental impacts, but also strengthen social ties within communities, promote inclusion and equality, and support peace-building efforts. Activities such as community dialogue workshops, joint natural resource management projects, or inclusive economic development initiatives could play a key role in reducing social tensions and creating a more stable and resilient environment in the face of climate shocks.

Above all, adaptation initiatives must avoid maladaptation. For example, one of the experts pointed out that internal migration caused by climate displacement could create new tensions, particularly in urban areas. Growing urbanization in these areas could overload local infrastructures, increase social inequalities, and even lead to conflict, especially when resources are limited. If adaptation policies fail to take these dynamics into account, they risk generating maladaptation, thereby aggravating social tensions. It is therefore essential to put in place interventions that take account of these migratory aspects in order to prevent new social imbalances, particularly in fast-growing urban centers. Thus, needs-oriented research, co-produced with users through transdisciplinary approaches, is required to ensure that interventions respond to different levels of social vulnerability and promote learning and exchange between communities.

A Conflict-Sensitive Approach to Climate Change Adaptation Projects: Strengthening Franco-Canadian Cooperation

A conflict-sensitive approach, especially in fragile contexts, is important because incorporating conflict sensitivity into climate adaptation interventions could not only help vulnerable communities adapt to the impacts of climate change, but also contribute to conflict prevention and the promotion of peace and stability. This approach, based on a deep understanding of local dynamics, cross-sectoral collaboration, and particular attention to social inclusion and gender equality, could have a positive impact on the lives of populations affected by climate change. Thus, for climate adaptation interventions to be sustainable and effective, the interventions supported by France and Canada should combine a thorough assessment, local capacity building, ongoing consultation with stakeholders, and particular attention to maladaptation prevention. By integrating these elements, both countries could maximize the positive impact of their interventions while contributing to peace and community resilience in the face of climate challenges. To further strengthen Franco-Canadian cooperation, it is essential to clarify the levels of collaboration between French and Canadian stakeholders responsible for project implementation.

This includes institutions such as the French Development Agency (AFD) and the International Development Research Centre (IDRC). For example, CLARE aims to strengthen resilience to climate change and natural hazards in African and Asia-Pacific countries through a portfolio of ongoing projects in Africa and Asia. The research supported by CLARE seeks to bridge critical gaps between science and action by developing new tools and supporting partner governments, communities, and the private sector to find effective solutions to climate challenges, while also building the capacity of researchers and users of research results.

As for the AdaptAction initiative, it supports 15 countries and regional organizations particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change in the implementation of their adaptation strategies, by offering technical assistance and capacity-building activities to strengthen their climate governance, and to better integrate climate change adaptation into their public policies. IDRC and AFD could draw on their respective experiences to exchange good practices, analyses, methodologies and experiences, and strengthen their approaches to integrate conflict sensitivity into climate change adaptation projects.

Ministries such as Global Affairs Canada (GAC) and the Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs should also be included. Cooperation between ministries, both in Canada and France, would allow for better consideration of the security and political dimensions of fragile contexts in climate project planning.

Therefore, it is recommended that an annual consultation unit be created that would bring together these key stakeholders. This unit could organize regular meetings to discuss ongoing projects, discuss progress made, and identify challenges to overcome in terms of conflict sensitivity and climate adaptation. Such a platform would foster exchanges between AFD, IDRC, the ministries involved, and other partner organizations, allowing for better coordination of efforts and the systematic consideration of local issues in project implementation. It would also provide an opportunity to discuss the integration of Do No Harm principles and gender analyses into adaptation strategies.

This consultation unit would also provide an inclusive forum for exchange where stakeholders and researchers from developing countries, community leaders, and local ministries from the relevant partner countries could share their knowledge and perspectives. To this end, collaboration with local organizations already involved in CLARE and AFD adaptation projects could be essential to ensure that the proposed solutions consider the cultural contexts and unique challenges of each region. The active presence of ministries, both on the Canadian and French sides, would also be crucial for integrating security dimensions into adaptation projects. Their expertise would help prevent the escalation of tensions in fragile contexts.

It should also be noted that Canada, through Global Affairs Canada (GAC), has already implemented guidelines on conflict sensitivity. This document does not represent official Government of Canada policy, but it does contain guidelines on best practices. It is specifically intended for organizations implementing GAC-funded projects and offers guidance for integrating a conflict sensitivity analysis. These guidelines could provide a solid foundation for guiding practices in funded projects and could be used as a reference to strengthen cooperation with France and coordinate actions on conflict sensitivity and climate adaptation, ensuring that approaches remain adapted to local realities.

Finally, the establishment of this annual consultation unit would not only allow for better coordination of Franco-Canadian efforts, but also maximize the benefits of climate interventions while avoiding exacerbating existing tensions. This approach and ongoing dialogue would make Franco-Canadian cooperation a model of collaboration that respects local dynamics, prioritizing inclusion, active listening, and the co-creation of solutions.

[1] This diagram illustrates the impact of interventions in conflict situations, from “Doing harm” to “Contributing to peace”. Conflict sensitivity is a fundamental basis for avoiding negative effects (Do No Harm) and reinforcing positive impacts (Do More Good). It highlights how sensitive approaches can prevent the escalation of tensions, address the structural causes of conflict, and support sustainable peace.

Comments are closed.