Context

Rooted in the Black American feminist movement of the 1980s and 1990s, the concept of intersectionality refers to the intersection of the various social, physiological and psychological identities of an individual that shape perception of the environment as well as experience of life. In 1995, in an effort to achieve parity and create a more inclusive society, the Canadian federal government committed to implementing a tool to advance gender equality in Canada as part of the ratification of the Beijing Platform of Action (Canada, 2018a). In the early 2000s, the Canadian government launched Gender-Based Analysis (GBA), a tool to promote the inclusion of gender differences in the development of programmes and policies and the elimination of discrimination towards women. In 2011, Status of Women Canada modernized its approach by introducing Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) to take into account other identity factors along with gender (Canada, 2018b). Since 2016, memoranda to Cabinet and presentations to the Treasury Board of Canada must include a GBA+. Moreover, Status of Women Canada has developed an online course to teach the basics of the tool to all and encourage public servants to apply GBA+ in their work. In addition to this tool, the Network for Strategic Analysis is committed to using an intersectional approach to achieve its objectives.

Implementation of an Intersectional Analysis

Gender-based analysis plus (GBA+)

GBA+ “is used to assess the potential impact of policies, programmes or initiatives on various groups of people – women, men and others” (Canada, 2018). The tool proposes a series of questions to ask before undertaking any research or activity in order to challenge the researcher or the analyst’s beliefs or biases. GBA+ has seven distinct stages: identifying main issues, challenging assumptions, gathering facts through research and consultation, formulating options and recommendations, monitoring and evaluating, and communicating (Canada, 2018).

Some researchers have noted the limits of GBA+, including that the tool is primarily based on analysis according to gender and sex before it includes other identity factors (Hankivsky & Mussell, 2018). In addition, the various factors are approached as independent categories that are added to each other, which goes against the very essence of an intersectional approach (Hankivsky & Mussell, 2018; Maillé, 2018). Some also noted that the long list of questions posed often results in a box ticking exercise rather than a real reflection on the inclusion of minority groups. Finally, we add that the discriminating factors are all grouped under the category “identity factors”, without any distinction as to their real nature.

Although our intersectionality strategy is inspired by GBA+, it innovates and goes beyond GBA+ to ensure that intersectionality is present in the collective work produced by researchers from the Network for Strategic Analysis and that this work reflects a great diversity and the inclusion of under-represented groups.

Our approach to intersectionality

Our intersectionality strategy holds that the perceptions and life experiences of individuals are shaped by several factors that may be discriminatory. The importance and effects of these factors may vary depending on the context and the situation. In addition, these factors do not operate independently, but interact with each other and can contribute to the formation of unique forms of discrimination.

Our strategy of intersectionality differs from GBA+ in three ways :

- The starting point is not necessarily gender -The starting point of our intersectionality strategy is not necessarily gender, but varies depending on the nature of the project or initiative. For example, in some cases, the main discriminating factor can be a physical handicap or even language, while gender can have a secondary influence.

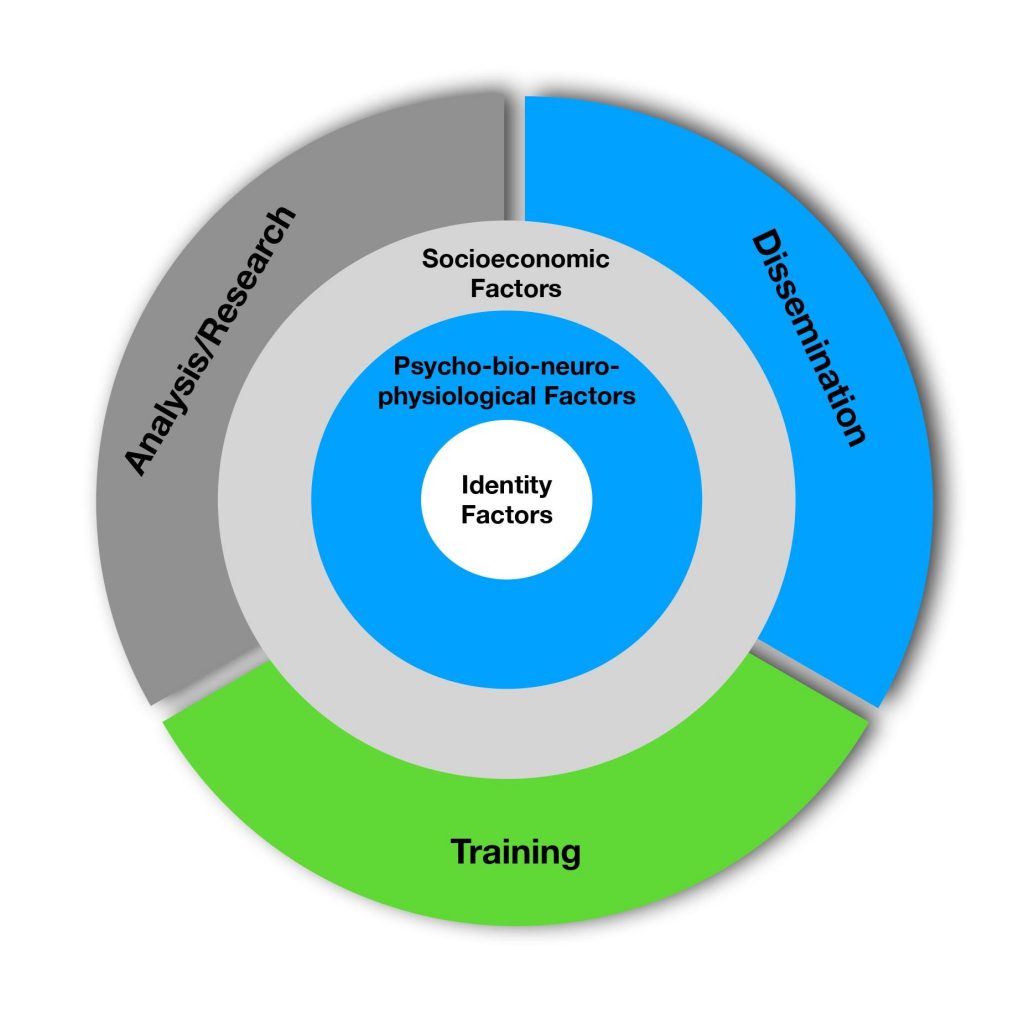

- The intersectionality strategy includes three types of discriminating factors

- Identity factors: Factors that define an individual’s identity. Identity factors include in particular gender, sexual identity, race, language, culture, ethnicity, sexual orientation, etc.

- Psycho- bio-neurophysiological factors: Psychological, biological, neurological or physiological factors that affect the way people perceive or experience the external environment. Psychological bio-neurophysiological factors include biological sex, age, physical or mental disability, physical appearance, learning styles, learning disorders, etc.

- Socio-economic factors: Features relating to the social or economic position of an individual that influences life experiences. Socio-economic factors include income, education, place of residence (rural vs. urban , region vs. centre, etc.), economic conditions in the community where an individual lives, employment status, marital status, family status, etc.

- The intersectionality strategy includes taking into account the relationship between the categories of discriminating factors – The various discriminating factors are not uniform categories that can simply be added on to each other. Our intersectionality strategy focuses specifically on the intersection of various discriminating factors to understand how the relationship between them affects how people perceive or live particular situations.

To go further, have a look at our video on thinking diversity of all kinds in strategic affairs.

How do I apply the intersectionality strategy to my work?

All the activities of the Network for Strategic Analysis can be grouped under three main categories:

- Research and analysis activities

- Dissemination of research results

- Training activities for new researchers and new practitioners

For each category, our strategy suggests answering three fundamental questions:

- What is the main discriminating factor?

- What are the other factors that influence or contribute to discrimination?

- How does the intersection between these factors affect analysis and research, the dissemination of results or the training of new researchers for certain individuals?

These three questions will require researchers to properly identify the subgroups likely to suffer discrimination. The type of data to be collected will vary according to the category of activities carried out.

Research and analysis activities

The results of research and analysis are frequently tainted with the beliefs and unconscious biases of the researchers. The samples studied are often considered to be homogeneous and the results obtained are thus generalized to the whole of a population which is also often conceived as a homogeneous whole. However, before undertaking research and analysis, it is important to consider the characteristics of the sample or population studied.

Take, for example, research looking at the retention of Indigenous recruits in the Canadian Armed Forces. It is possible that the reasons prompting some recruits to leave the organisation depend on various factors. In this case, the primary discriminating factor will be Indigenous origin: it will be interesting to first understand the difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous recruits’ reasons to leave the organisation. However, since the “ Indigenous ” category is not homogeneous , it is important to identify other factors that can affect the experience of recruits. For example, is there a difference between men and women? Does having lived on a reserve or not influence the recruit’s decision? Does family situation influence choice? How do these various factors interact? Are reasons for leaving the organisation the same for a single Indigenous man from an urban centre and for a single-parent Indigenous woman from a more distant region? Can other factors interact and shape the experience of these Indigenous recruits?

Before undertaking a research or analysis activity, it is therefore important to note the factors likely to influence the experience of certain individuals or sub-segments of the population and to carry out more detailed and specific research in order to avoid generalisations that fail to take into account the specificity of the experiences of certain under-represented groups.

Dissemination of academic research results

The tools for disseminating research results are most often intended for an educated audience and are frequently not well suited to a wider audience. Before embarking on the development of media to disseminate information, it is important to understand the diversity of the target audience in order to adapt the modes of communication. For example, in the case of an information note aimed at informing practitioners of research results, the main discriminating factor will be level of education. One might wonder whether the note is written in accessible language and free from hermetic scientific jargon. Furthermore, depending on the target audience, it is important to ask whether people with visual impairments can have access to the information note. If the note is translated, is the translation faithful and does it reflect the reality specific to the other language? Do the examples and expressions used have meaning for all individuals who will read this note so that they understand the message, or are they specific to the dominant culture? Is the format easily accessible for all?

Before developing a tool for disseminating research results, it is therefore important to note the factors likely to influence or limit the understanding of recipients, in order to avoid limiting access to knowledge to certain groups who are under-represented in our society.

Training activities for new researchers and new practitioners

Training programs are often designed to meet the needs of an audience with little diversity. However, in order to maximize the scope of training activities for new researchers and new practitioners, it is important to clearly define the characteristics of the participants and to adapt the activities to their various needs and realities. For example, in the case of setting up a postdoctoral fellowship programme to develop the bilingual expertise of young Canadian researchers, the main discriminating factor will be language. The reality of young French-speaking researchers differs considerably from that of young English-speaking researchers since French remains a minority language in all of Canada, except in Quebec, which is likely to influence everyone’s experience. How does the learning experience of an Indigenous postdoctoral trainee speaking mainly French and living in Quebec differ from that of a Black postdoctoral trainee speaking English and living in Western Canada? Finally, other factors such as neurological, physiological or psychological handicaps (e.g. dyslexia, anxiety disorders, etc.) can also shape the learning experience.

Before designing training for new researchers and new practitioners, it is therefore important to identify factors that may influence learning experiences and to develop programmes that are well suited to a diverse population in order to allow participants to make the most of their experience.

The following graphic illustrates our intersectionality strategy:

Evaluating the implementation of the intersectionality strategy

The Network for Strategic Analysis’s management team is committed to presenting an annual report on the intersectionality strategy to the Scientific Council; this assessment is to enable us to adjust our operations to ensure that they include great diversity and under-represented groups. To this end, we ask all members of the network to fill out a short form (below) to note the discriminating factors that they have identified, as well as the measures taken to consider the uniqueness of the experience of certain minority groups in our society. The form must then be sent to Isabelle Caron, responsible for implementing the intersectionality strategy for the Network for Strategic Analysis.

Link to the form : https://forms.gle/YyK8LBozEGmzVVaj8

To go further

- Canada, “What is GBA+?,” Status of Women Canada, 2018.

- Olena Hankivsky, “Intersectionality 101,” The Institute for Intersectionality Research and Policy, Simon Fraser University (2014).

- Chantal Maillé, “Intersectionalizing gender policies: Experiences in Quebec and Canada” French Politics 16:3 (2018): 312-327.

- Olena Hankivsky & Linda Mussell, “Gender-Based Analysis Plus in Canada: Problems and Possibilities of Integrating Intersectionality,” Canadian Public Policy 44:4 (2018): 303-316.

Comments are closed.