Abstract

Mackinder’s work on the Heartland (1904) seems to have generated a lot of interest since the advent in 2013 of the Chinese New Silk Road project, or Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). With its emphasis on continental links extending across Central Asia, the similarity between the BRI and Mackinder’s theory was noticed by many analysts, who now see in the Heartland model a relevant reading grid for understanding the Chinese politics of the BRI. But is this conceptual model really relevant? It appears that it does not adequately depict reality.

Introduction

Geopolitical modeling is a controversial scientific project. The ambition to forge a global and permanent analytical model to account for the relation between space and power gave rise to important research, including that of authors like Spykman and Mackinder. These publications, in particular Mackinder’s introduction of the Heartland theory (1904), have generated a great deal of interest since the advent in 2013 of the ambitious Chinese New Silk Road project, or Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). With its emphasis on continental links spanning Central Asia, the similarity between the BRI and Mackinder’s theory has struck many analysts, who see now in the Heartland model a relevant analytical grid to study the Chinese policy of the BRI. But is this conceptual model really relevant? This article describes how the Heartland model is mobilized in the context of the development of the Chinese BRI, and highlights the scientific risks of relying on analytical models at the expense of empirical and grounded research. For a better understanding of the BRI, it appears more relevant to rely on empirical research.

Mackinder’s geopolitical theory and its timeless model

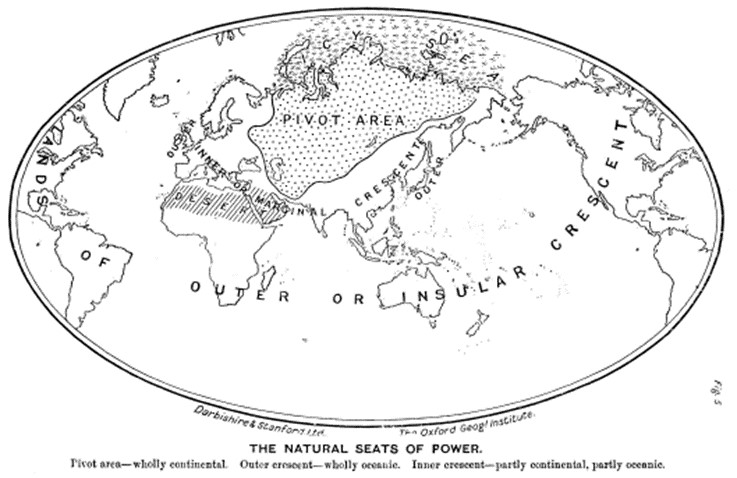

The Heartland theory is the name given to a global geopolitical analysis of world history proposed by the British geographer Halford Mackinder (1861-1947). Mackinder endeavored to understand the mechanisms of world history, with a view to defining general rules describing the equilibrium of power.

In the article he published in 1904, Mackinder sought to unveil “a correlation between the larger geographical and the larger historical generalizations” (Mackinder, 1904, p.422). Mackinder associates a pivotal area, the Heartland, with the general direction of world history. However, the existence of a pivotal region in the political history of the world is invoked but never explained. In 1919, in his book Democratic Ideals and Reality, Mackinder came up with his famous predicate:

Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland

Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island

Who rules the World-Island commands the World.

(Mackinder, 1919, p.194).

Fig. 1. Location of the pivot zone or heart-land in Mackinder’s theory (1904). Source: Mackinder (1904), p.435.

In 1943, Mackinder again mobilized his Heartland theory. He warned that if, as a result of the then ongoing Second World War, Moscow could extend its territory westward, the USSR would become the “greatest land power on the globe” (Mackinder, 1943, p.601). However, this prospective reasoning is no more grounded in an empirical geographical analysis than the 1904 paper or the 1919 book.

Another geographer and early thinker in geopolitics, Nicholas Spykman, came up with a diametrically opposite position on the basis of the same type of reasoning: a historical analysis, just as Eurocentric as that of Mackinder, that led him to a final conclusion that asserted the contrary to Mackinder’s mantra:

Who controls the Rimland rules Eurasia, who rules Eurasia controls the destinies of the world. (Spykman, 1944, p.43).

In Spykman’s analysis, it is within the Rimland[1] that the basis of power lies, and not in the Heartland. But neither Spykman nor Mackinder provide tangible elements of demonstration to support their thesis, and fail to establish a credible causal link, an explanatory relationship between the areas they studied and historical events.

The advent of China’s Belt and Road Initiative: the confirmation of Mackinder’s model?

In the past few years several authors have made a direct link between Mackinder’s Heartland theory and the Chinese BRI. The BRI articulates the development of major development corridors (NDRC 2015), resting on the exploitation of major trans-Asian railways that bring to mind Mackinder’s analysis: “Trans-continental railways are now transmuting the conditions of land-power, and nowhere can they have such effect as in the closed heart-land of Euro-Asia.” (Mackinder, 1904, p.434).

Thus, Wey (2019) notes a strong correlation between Mackinder’s theory and the maritime and continental developments of the BRI. Invoking this theory, Wey concludes that “If this geopolitical strategy is successful, China will ‘rule the Heartland’ and ‘command’ the seas” (p.3). Harper (2019) underlines the fact that Chinese expansion on the Asian continent upsets the United States’ interests: “One of the immediate implications of the BRI for the other external actors present in Eurasia is as a potential challenge… […]. It is this challenge that raises the spectre of Mackinder’s depictions of Eurasia with the BRI’s land corridors being a means to bypass maritime routes, which would adversely affect one of Washington’s primary strategic advantages in the form of its navy.” (p.117). Shukhla (2015) sees a direct parallel between the many BRI rail projects in Central Asia, the Middle East and Southeast Asia, and Mackinder’s theory, in which the rail expansion of Russia is presented as a threat. Yu (2019, p.196) suggests that “The rivalry over the Eurasian Heartland marks a historical return of Mackinder’s Heartland theory”.

Several authors thus draw a parallel between the developments of the BRI and Mackinder’s theory, seeing in this parallel the proof that China nurtures a world strategy and seeks the upheaval of the world order, a reasoning based largely on unreserved adherence to Mackinder’s theory. “From a purely geographic perspective, the trajectory of the planned land-based New Silk Road (the Belt) aligns to a significant degree with Mackinder’s Heartland theory” (Shortgen, 2018, p.27).

“The Eurasian heartland remains the world’s geopolitical pivot, an idea as true a hundred years ago as it is today. The Eurasian heartland is the BRI’s birthplace, a necessary corridor for the Chinese-envisioned new continental economic reality” (Yu, 2019, p.10). The Chinese strategy towards the Middle East constitutes “a global strategy designed to fulfill Chinese geopolitical ambitions”. The Chinese authorities reportedly relied on Mackinder’s pronouncements: “Lying at the heart of Mackinder’s World-Island (1904), the Middle East represents a pivot for the development of China’s sphere of influence, since ‘who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island, who rules the World-Island commands the World’ ” (Maury et al, 2019, p.61).

Other authors see in China’s projects the proof of the validity of Mackinder’s theory: “China’s cooperation with Russia, its Belt and Road Initiative, its growing presence in the Indian Ocean and Africa, and its burgeoning sea power are evidence of Mackinder’s prophetic powers” (Sempa, 2019).

An outdated scientific debate

However, several authors have already noted the scientific lightness of Mackinder’s and Spykman’s theses. Ó Tuathail (1996) studied the mythical and oriented dimension of Mackinder’s theory, aimed at proposing a model capable of legitimizing British policy in Central Asia. Venier (2010) pointed out the absence of a “rigorous demonstration” of Mackinder’s theory. The heritage of these theoretical models from the so-called materialist school no longer poses an epistemological problem for the geographic school in geopolitics, whose researchers consider the works of Mackinder or Spykman as dated moments, milestones in the history of geopolitical thinking, but with little scientific value.

The political sciences and geography were, at the beginning of the 20th century, in search of a scientific respectability in the identification of laws of the political realm that clearly stated the formal mechanisms that connect space to power (Lasserre et al, 2020a). This chimera of the materialist school is outdated today, but it has left a lasting mark on reflections in geopolitics. “At a time when the principles of causality and determination are the universal references, geography thinks it can hold with domination or the struggle for space its ready-made explanation” (Dussouy, 2006, p.112). As Entin and Entina underlined (2016, p.341), “It is not a surprise that Mackinder’s theory remains popular even now. Such simple, beautiful, artificial, convenient and all-explaining teachings are always in demand and easier to accept”. However, the value of geopolitics does not lie in prediction, an often risky venture, but in analysis: “geopolitics revisited, far from all prophecy, unveils a world of possibilities” (Dussouy, 2001, p.50).

A contemporary popularity, the reflection of Western fears?

Why then put so much emphasis on Mackinder’s model when discussing Chinese projects, rather than that of Spykman, two equally globalizing and undemonstrated theories?

Chinese authors rarely refer to Mackinder’s theoretical model, but rather to Chinese authors like Sun Tzu (Boillot, 2020). In addition, the plethora of maps in circulation representing the projects of Chinese corridors enclosing Central Asia and the maritime routes in an embrace often portrayed as threatening is an approach also to be taken with caution. Most of these maps are false (Lasserre et al, 2020b) and unofficial – the Chinese government having banned the production of such approximate maps in 2017 (Jones and Zeng, 2019, p.1425). The media and several researchers, including those who are Chinese, have been deceived by these inaccurate maps.

Interpreting a political strategy with a theory based on the reading of another rivalry (Russia and the British Empire), and, above all, an unproven and highly questionable theory on a scientific level, is not new. Several authors have already pointed out that Mackinder’s theory was widely used in Washington in the creation of American policy to counter the Soviet Union during the Cold War (Parker 1988, Sloan 1988; Brzezinski 1997).

A similar posture seems to contribute to contemporary Western fears over the BRI’s land strategy, which is consistent with:

…an American tradition of focusing on map-based geopolitical and geostrategic thinking. This ‘cartohypnosis’ goes back to Halford Mackinder’s portrayal of the Eurasian landmass as the global ‘Heartland’. Stemming from Mackinder’s geopolitics, the idea of needing to prevent the Soviet Union from controlling this ‘Heartland’ […] governed much of American strategy during the Cold War […]. Thus, it is understandable that the BRI could easily be seen by Americans thinking in this tradition as a Chinese ‘great game’ intended to extend its geopolitical influence westward (Garlick, 2020, p.110).

Debié agrees:

Thus the success of Mackinder or Spykman during the Cold War, the renewed interest in Haushofer seem inspired by the cartographic exercise. The experts from the Pentagon or the Department of State who, on the maps of the fifties, see the red spot growing in central Eurasia and compare the cartographic models of Mackinder or Spykman, are struck by the resemblance. Soon, they are convinced of the prophetic value of the models and the genius of their authors, since the map drawn in 1904 or in 1944 predicted what is happening in the years 1947-56. (Debié, 1991).

Thus, like Mackinder and Spykman, it appears that the attraction of these theoretical models and their global cartographic support is their correspondence with the concerns of the hour. Mackinder deliberately devised a model presented as eternal but which in reality rests on a reading of the British rivalry with Russia, then on the fear of the USSR. The same is true for the Spykman model, which is just as general in its discourse, but geared towards the containment of the Soviet Union. At the time of the advent of China as a new great power, it appears that the renewed interest in Mackinder’s theory could reflect the fear of Westerners that their political pre-eminence is being undermined.

Implications for Canada

Mackinder’s model, reflecting the state of geopolitical thinking in the early 20th century, can only prove a poor tool to account for China’s projects in Asia through the BRI. It appears that even if the temptation to mobilize a geopolitical model to grapple with the complexity of the BRI is understandable, it may not provide fruitful analyses. Mackinder’s Heartland model was designed in a specific context of great power rivalry between Russia and Britain with a view to demonstrating what Mackinder perceived as the urgency of protecting Britain’s interests in South and Central Asia. The model is thus specifically and contextually oriented, if not flawed, as Mackinder built it to underline Russia’s threat. Besides, it overestimates the potential for conflict and deliberately minimizes other elements like cooperation, trade and domestic geopolitics.

In order to develop a better understanding of the security implications of the BRI, one must not rely on antiquated and simplistic models that cannot account for the complexity of the present-day reality. For Canadian scientists and government analysts, an effective approach to China’s ‘New Silk Road’ development strategy must take into account the specifics of the present BRI, of 21st century Asia, and consider the following:

- China’s BRI does not merely boil down to transportation, but this is a major dimension of the project. However, several of the corridors and transportation axes developed by the BRI predate the 2013 announcement and were often designed by other countries or institutions (Lasserre 2019): they thus reflect the interests of several countries and not merely China’s interest. Analyzing the BRI merely through the prism of China’s interest is thus deceiving.

- The political parameters that orient the development of the BRI projects largely reflect local or regional geoeconomic considerations. The first development of trans-Asian railway services was largely driven by Western manufacturers and the German railway company Deutsche Bahn in order to improve their logistics and connect European and Chinese subsidiary production plants. China also holds the project dear as it considers it a tool to develop the unrest-prone Xinjiang region. A good understanding of local social, economic and political realities is a prerequisite for an effective understanding of the stakes of the BRI strategy.

- If the BRI is now reckoned by several researchers as having geopolitical dimensions, it would be short-sighted to consider it as a mere political tool designed to foster China’s power. The BRI is an opportunistic development strategy that integrates many economic sectors (including, for example, transportation, telecommunications, energy, health, tourism, education, and culture) in various regions according to as-yet undefined and very general criteria, several of them responding to Chinese domestic political and administrative mechanisms (Jones and Zeng, 2019) but also to partner states’ desires. Taking into account the mechanisms for the governance of the several BRI projects is thus necessary to avoid errors.

- The lack of systematic criteria in the governance of the BRI may reflect this strategy still being in its early stage. There is mounting pressure from China’s partner states, institutions and the media for the Chinese government and banks to be more transparent and rigorous in the adjudication of projects. The Hambantota failure[2] was not a ploy designed by China to put Sri Lanka into debt and eventually take over the port, contrary to several accounts; rather it was the result of corrupt planning by local authorities and overenthusiasm by Chinese banking authorities. For Canada to be able to take advantage of this trend, it must be part of the solution, not reject the BRI, and thus actively participate in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and suggest participation in development projects.

[1] The Sri Lankan port was granted to China in 2017 on a 99-year lease after the Sri Lankan state proved unable to service its staggering debt. The port, built in the president’s home area, failed to make profits.

[2] The Rimland, or Inner Crescent, is Eurasia’s littoral area, the densely populated western, southern and eastern fringes of the world open to maritime trade.

References

Boillot, J.-J. (2020). Les routes de la soie et le 36e stratagème. Diplomatie 101, 46.

Debié, F. (1991). La géopolitique est-elle une science? Un aspect de la géographie politique de Peter Taylor. Stratégique n°50.

Dussouy, G. (2001). Quelle géopolitique au XXIe siècle? Bruxelles: Complexe.

Dussouy, G. (2006). Les théories géopolitiques. Traité de Relations Internationales I. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Entin, M. & Entina, E. (2016). Russia’s role in promoting Great Eurasia geopolitical project. Rivista di Studi Politici Internazionali, 83(3), 331-351.

Garlick, J. (2020). The Impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative from Asia to Europe. London: Routledge.

Harper, T. (2019). China’s Eurasia: the Belt and Road Initiative and the Creation of a New Eurasian Power. The Chinese Journal of Global Governance, 5(2), 99-121.

Jones, L. & Zeng, J. (2019) Understanding China’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative’: beyond ‘grand strategy’ to a state transformation analysis, Third World Quarterly, 40(8), 1415-1439.

Lasserre, F. (2019). Les corridors transasiatiques: une idée ancienne opportunément reprise par la Chine. In Lasserre, F.; É Mottet and B. Courmont (eds.) (2019). Les nouvelles routes de la soie. Géopolitique d’un grand projet chinois. Québec, PUQ, 31-54.

Lasserre, F., Gonon, E. and Mottet, É. (2020a). Manuel de géopolitique. Enjeux de pouvoir sur des territoires. Paris, Armand Colin.

Lasserre, F.; Huang, L. and Mottet, É. (2020b). The Emergence of Trans-Asian Rail Freight Traffic as Part of the Belt and Road Initiative: Development and Limits. China Perspectives, 2020/2, 43-52.

Leong Kok Wey, A. (2019). A Mackinder–Mahan Geopolitical View of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. RUSI Newsbrief 39(6), London: Royal United Services Institute, https://rusi.org/sites/default/files/20190705_newsbrief_vol39_no6_wey_web.pdf

Mackinder, H. (1904). The Geographical Pivot of History. The Geographical Journal, 23(4), 421-437.

Mackinder, H. (1919). Democratic Ideals and Reality. A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction. London: Constable and Cie.

Mackinder, H. (1943). The Round World and the Winning of the Peace. Foreign Affairs, 21(4), 595-605.

Maury, B.; Struye de Swielande, T. and Vandamme, D. (2019). Les nouvelles routes de la soie au Moyen-Orient: complexité d’une région essentielle pour la Chine. Diplomatie 101, 58-61.

NDRC, National Development and Reform Commission (2015). Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road. Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1249618.shtml.

Ó Tuathail, G. (1996). Critical geopolitics: the politics of writing global space. London: Routledge.

Parker, G. (1988). The Geopolitics of Domination. London: Routledge.

Sempa, F. (2019). China and the World-Island. Today’s strategists should keep Mackinder in mind when looking at China’s efforts across Eurasia and Africa. The Diplomat, Jan. 26, https://thediplomat.com/2019/01/china-and-the-world-island/.

Shortgen, F. (2018). China and the Twenty-First Century Silk Roads: a New Era of Global Economic Leadership? In Zhang, W.; Alon, I. and Lattemann, C. (eds.), China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Changing the Rules of Globaliszation, p.17-33. Cham: Palgrave.

Shukhla, A. (2015). Understanding the Chinese One-Belt-One-Road. Mackinder Redux: Struggle for Eurasia after the Cold War. Vivekananda International Foundation, Occasional Paper, https://www.vifindia.org/sites/default/files/understanding-the-chinese-one-belt-one-road.pdf.

Sloan, G. (1988). Geopolitics in United States Strategic Policy. Brighton: Wheatsheaf Books.

Spykman, N. (1944). The Geography of the Peace, ed. by Helen R. Nicholl. New York: Harcourt Brace and Co.

Venier, P. (2010). Main Theoretical Currents in Geopolitical Thought in the Twentieth Century. L’Espace Politique 12|2010-3, http://espacepolitique.revues.org/1714

Yu, S. (2019). The Belt and Road Initiative: Modernity, Geopolitics and the Developing Global Order. Asian Affairs, 50(2), 187-201.

Comments are closed.