Despite periodic instances of tension and disagreement, Ottawa has leaned heavily on its relationship with Washington to anchor its foreign policy throughout the postwar era. The bipolar Soviet-American standoff provided Canada with an opportunity to entrench itself within the US-led Western bloc for security purposes. The Cold War’s unipolar aftermath further deepened the logic of Canadian dependence on the United States – not only in economic terms following the advent of free trade, but also geopolitically and psychologically as Washington sought to expand the reaches of the Western-led liberal international order across the globe.

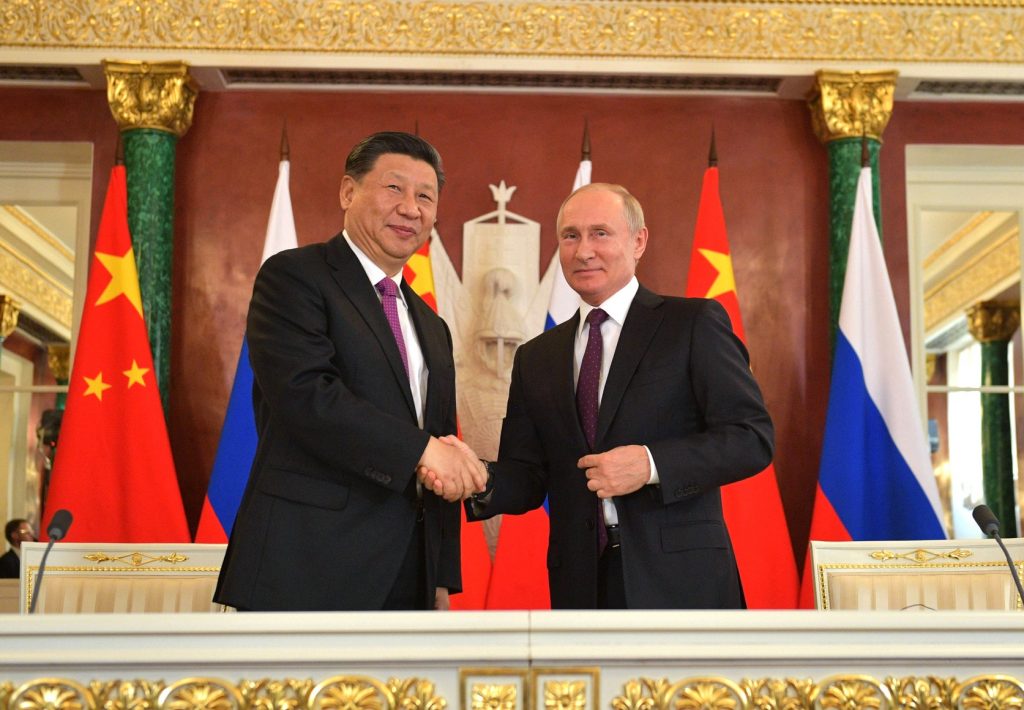

This post-Cold War effort to create a liberal world order of universal scope has now failed. Emerging in its wake is a period of uncertainty and great power rivalry likely to endure through this nascent decade if not beyond. And although rules-based multilateralism is not entirely incompatible with multipolarity, the notion of a Western-led global order rooted in liberal values manifestly is. In fact, current dynamics favour the continuation of broadly zero-sum relations between the United States and the Sino-Russian entente, whether US foreign policy reembraces alliances and liberal internationalism or continues its trend toward a more amoral defence of American global primacy. Such an outcome is inimical to Canadian interests.

As a result, Canada needs to begin cultivating an increasingly independent national posture toward Europe and the Asia-Pacific, where its overriding interest remains the preservation of a stable security order. The realities of geography and power guarantee that Washington will remain Ottawa’s primary economic and security partner. However, as a trading nation that depends heavily on a rules-based international framework, Canada must provide a degree of equilibrium to its heavily US-centric post-Cold War foreign policy if it wishes to be a rule-maker and not a rule-taker. As the pressures of an increasingly rivalrous world have begun to bear direct consequences for Canada in recent years, the need for a recalibration has become evident.

Canada and the US-China Cold War

There is a common notion in Western policy circles that Russia and China are revisionist powers bent on overturning the international order. However, Moscow and Beijing can also be seen to have status quo aims: the Kremlin wishes to maintain Russia’s great power status after having emerged from the Cold War in a weakened state, while the Chinese Communist Party seeks to retain power in part by preserving the international conditions necessary to continue China’s economic modernization. As such, the threat to the established rules-based order does not emanate from any single power, but rather from the zero-sum nature of great power relations that is the inevitable structural outcome of the current moment.

As US-China relations have grown more fraught, Canada has been caught uncomfortably in the middle. American efforts to crack down on Huawei and limit the prospects for Canada-China trade as agreed in the USMCA deal have led to the arrest of two Canadian citizens in China and the broader deterioration of ties between Ottawa and Beijing. This outcome is less the product of Canada’s specific disputes with China and more the result of Ottawa’s failure to develop a broader strategic paradigm to guide its relations with competing great powers. Canada’s inability thus far to adapt to the realities of the new world is evidenced by its declining or challenged relations not only with China, but also with India, Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United States.

Examples of increasing competition in Sino-American relations predate the Trump administration. President Obama announced his country’s strategic “Pivot to Asia” and undertook efforts to prevent US allies from joining the Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, while Beijing’s launch of the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013 aimed to elevate China above the status of regional power. The subsequent US-China trade war and COVID-19 pandemic mark the intensification and consolidation of this dynamic of open hostility. In this context, China has treated the pandemic as a dual internal-external national security crisis and has moved toward an increasingly assertive international posture. This, in turn, has led to greater alignment among members of the Quad composed of the United States, Japan, Australia and India. Although liberal internationalists have made the defence and reinvigoration of American alliances a central component of their critique of President Trump, this regional trend toward a bipolar standoff is likely to continue regardless of who occupies the White House.

Ironically, although US strategy is nominally geared toward preserving a “free and open Indo-Pacific”, the consolidation of an economically weaponized Sino-American cold war threatens the open and rules-based character of regional trade. This would limit Canada’s opportunities to diversify its trading partners – a key pillar of any independent Canadian foreign policy. That said, China’s growing assertiveness and overstretched aspirations have helped to paint it into a corner. And while China’s rise followed the initial postwar emergence of Japan and the Asian Tigers as economic powers, the next wave of Asian growth favouring India and ASEAN will lead to Beijing’s relative decline. China’s current hunkering down and increasingly inflexible conduct could therefore be aimed at carving out a regional order favourable to the pursuit and preservation of its core interests before its ability to secure them becomes reduced.

Regional Order in a Multipolar Europe

The United States has also made a concerted effort to co-opt its European partners into its struggle for pre-eminence with China. This reveals the extent to which Washington has pivoted toward Asia since the early post-Cold War decades, prioritizing global strategic considerations ahead of the pursuit of a stable European security order. With the EU having failed to construct a Brussels-centric regulatory and political order spanning the entirety of the continent, Washington’s psychological disengagement from Europe leaves a post-Brexit EU stuck in a multipolar regional order that also includes Russia and Turkey. The US-led transatlantic alliance, which excludes the European continent’s most militarily powerful actor (Russia), cannot act as the sole guarantor of a stable regional security framework in this context.

Yet despite unresolved questions surrounding the future of American leadership, Washington has not abdicated its desire to maintain regional primacy in Europe, while Moscow remains unwilling to initiate a genuine rapprochement with Brussels due to uncertainty over the EU’s potential to emerge as a truly autonomous security actor. Both of these factors guarantee the continuation of regional tensions. Moreover, growing instability in Europe cannot be attributed uniquely to a lack of US leadership. Turkey’s increasing willingness to use hard power as a means of advancing its strategic interests has been bolstered by the vacuum of power in Libya, which itself is the product of American overstretch in having brought about the collapse of the Gaddafi regime in 2011.

The brief post-Cold War era of American primacy created the illusion that a Western-led international order could be global in scope and rooted in shared values. Canada has a vital interest in ensuring that the decline of this liberal order is not replaced by a world rooted in spheres of influence. Yet all three major global powers – the US, China and Russia – appear to be pursuing strategies that are in some way aimed at just that: pre-emptively carving out regional arrangements in a zero-sum contest to compensate for their internal political fragility and hedge against the possibility of their relative decline over the medium-term. The United States in particular, facing a multitude of socioeconomic and political challenges, is unlikely to be amenable to revising the fundamental tenets of its primacy-oriented international posture. Major powers only have so much influence in a world based on universal sovereign statehood, but this forthcoming decade precedes the potential future consolidation of Europe and rise of both Africa and the Asian Rimland. In the interim, the US-Russia-China triangle is likely to play a substantial role in shaping the contours of the emerging global order.

Conclusion

In an increasingly competitive world, Canada no longer finds itself insulated by its geographic isolation or American unipolarity. Rising tensions in Europe and the Asia-Pacific – two theatres which Canada directly abuts – threaten to impose economic and security-related pressures that constrain Canadian freedom of action. In response to the growing divergence of interests between Canada and the United States, the opportunity is ripe for Ottawa to advance its own visions of regional security and play a more active role in upholding global order.

With respect to Asia, Canada should seek to paint a contrast with the Quad, backing Washington in any efforts to preserve an open regional order but resisting plans aimed at containing China. Ottawa should oppose any aggressive moves by Beijing to entrench a Chinese sphere of influence in places such as the South China Sea. However, it should welcome China’s desire to play a regional role commensurate with its growing influence, acknowledge the legitimacy of its security concerns, and help to guide it toward a global posture that is more in line with its still-fledgling capabilities. This would mark a shift from Canada’s recent China policy rooted in engagement for engagement’s sake, moving instead toward a more strategic but non-alarmist approach aimed at positioning Canada a defender of stability and a trusted interlocutor for all parties. This is not a call for equidistance between the US and China, but rather an appeal to incorporate a more conceptually developed equilibrium into Canadian foreign policy designed to adjust to new international pressures and keep open future opportunities for trade diversification.

In the case of Europe, without compromising its position as a leading member of NATO or acquiescing to Russian territorial revisionism, Canada should openly indicate its preference for a stable European security order and announce its readiness to engage in dialogue with all parties to that end. The medium-term relative decline of the US has led to the re-emergence of Eurasia at the centre of global power. Even if demographic and other trends favour a renewed period of American dominance over the long term, a strategic paradigm geared toward balancing between Eurasia and the US will help ensure that Canada emerges from this period of instability as an independent player with a growing economy and a diplomatically interconnected hub capable of using its neighbour to the south as a power multiplier on a global scale.

Comments are closed.