This policy report explores the extent to which the concept of Arctic Exceptionalism collides with the return to great power politics, particularly Russia’s resurgent strategic behaviour in the High North and China’s attempt to increase its influence in and access to the Arctic region.

Background

The Arctic is a zone of both cooperation and strategic competition concurrently. Cooperative Circumpolar relations are enabled through a number of key regional institutions and agreements, such as the Arctic Council, the United Nations Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) convention,[1] the Ilulissat Declaration,[2] and the Polar Code. These institutions facilitate intergovernmental cooperation, primarily on non-security issues, focusing on matters such as resolving territorial disputes, administering the maritime domain, environmental protection, and economic development. Although the Arctic Council does manage Search and Rescue cooperation, there is no overarching regional mechanism that manages Arctic security matters in the military domain.

Although the Arctic played a role in the strategic competition between the United States and Russia during the Cold War, the threats comprised strategic bomber aircraft and ICBMs coming over the pole to threaten North America, and submarine operations under the Arctic sea ice concerned deployed ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) and hunter-killer submarines (SSNs) that threatened them. The Arctic region was otherwise not accessible the way it has become today as a result of climate change altering the seasons so that the Arctic is ice-free for longer periods of the year, opening up the region to increased navigation, resource exploration, and scientific research. Today’s challenges are multifaceted and involve traditional and non-traditional security threats. The former concerns the increasing military activity by coastal Arctic states to defend, deter, enhance national sovereignty, and respond to emergencies; and the latter is related to the effects of climate change at the regional level on Northern peoples, infrastructure, and wildlife. The strategic dimension of Arctic security is of particular interest in this paper, with a look at how Russian Arctic military behaviour and Chinese Arctic ambitions challenge the cooperative paradigm of the region, often referred to as Arctic Exceptionalism. The emergence of a regional security dilemma does not necessarily negate cooperation in the Arctic but it does introduce challenging variables that affect how competitor states relate to one another.

What is Arctic Exceptionalism? Käpylä and Mikkola describe the Arctic as being seen “as relatively encapsulated from global power politics, characterized primarily as an apolitical space of regional governance, functional co-operation, and peaceful co-existence.” They suggest that in spite of becoming an increasingly global region with uncertainty introduced by Russian and U.S. foreign policy behaviour in recent times, Arctic “exceptionalism has shown continuing resilience as Arctic actors have actively tried to maintain regional co-operation in a difficult international environment.”

There is a debate among Arctic security scholars about whether Arctic Exceptionalism remains a valid concept in a changing regional context. Gjørv and Hodgson assert that Arctic Exceptionalism “describes a selective condition of security,” proposing a more appropriate analytical tool, namely Comprehensive Security, that “neither rejects processes of cooperation, nor denies areas of tension that foster increased perceptions of insecurity.” They argue that the framing of the Arctic as exceptional “owes much to the timing and the context under which Arctic regional relations were institutionalized.” Thus, a changing global and regional security context will see the emergence of new Arctic dynamics that may impact the cooperative paradigm.

Whether cooperative and peaceful conditions will endure in light of the provocative military behaviour of Russia, increasing exercises in the European Arctic by NATO allies and partners, and China’s economic ambitions in the region, remains to be seen. The risk of conflict in the region is low, as it is in the interests of states with stakes in the region to maintain peaceful cooperative relations. But the potential for misunderstandings and spillover of conflicts in other regions into the Arctic creates challenges. Of particular concern is the deployment of destabilizing conventional and nuclear weapons systems by Russia in its Arctic territory, and the U.S. response to counter new technologies in all domains.

Discussion

The Arctic region is increasing in strategic importance and economic potential. A low to moderate security dilemma is forming in the Arctic as a result of great power competition and the tension and uncertainty it introduces among key regional actors. A security dilemma describes conditions in which a state’s attempts to increase its security through the development of defensive capabilities makes other states (particularly competitor states) perceive that state as becoming a potential aggressor. The perception of threat and resulting vulnerability causes the other states to respond with developing defenses of their own, which causes the first state to perceive those states’ military behaviour as aggressive. The resulting militarization and tension between competitor states is the outcome of those states seeking to increase their own security.

The primary great powers in the region are: 1) a resurgent Russia remilitarizing its Arctic by refurbishing Cold War era base and building new ones; 2) a revisionist China seeking regional influence to advance its economic and scientific interests in the Arctic; and 3) the United States pivoting to the Arctic in response to environmental conditions resulting from climate change, as well as new strategic challenges posed by competitor states. Great power competition is occurring on a global scale and regionally as peer competitors pursue long-term economic and security interests in the Arctic. The challenges involve potentially provocative developments by the great powers and the absence of a regional organization or forum to manage military-security issues. There is the emerging challenge of the growing strategic cooperation between Russia and China; and both states are increasing their missile capability with the intention to hold at risk critical sites in the U.S. and Canada.

What is the impact of great power competition on security and stability in the Arctic? As discussed, security has a range of meanings, from the non-traditional human, environmental, social, and economic dimensions, to the traditional realist political-strategic domain. Stability tends to be reinforced through formal institutions and informal arrangements, and adherence to legal regimes and norms of behaviour. Predictability is enhanced through transparency and dialogue. State (and non-state) behaviours that violate these established standards of behaviour undermine stability and security. This creates conditions of tension among actors underlined by mistrust, uncertainty, and fear, which can impact the institutions intended to maintain a cooperative order in the region. The challenges posed by global actions – such as military developments and tensions in other parts of the world – can have regional implications. Tensions could spill over into the Arctic or a confrontation could escalate to a crisis due to miscalculation and misunderstanding. The outcome could see states withdrawing from agreements, wedges driven between states, and between states and their citizens (for example, between indigenous peoples and the state, such as Greenland/Denmark), and the weakening of institutions and arrangements. For instance, the U.S. and Russia engaged in military cooperation from 2009-2012. Russia and Western nations participated in the Arctic Security Round Table (ASFR) and Northern Chiefs of Defence Conference (NCDC), which allowed them to build trust and confidence. However, after the Russian annexation of Crimea and Russia’s actions aiding separatists in Donbas (Ukraine) military cooperation between the West and Russia were suspended, as tension and mistrust increased (this was observed when Russia withdrew from participating in the Arctic Security Round Table and the Arctic Chiefs of Defence forum.

China’s Arctic Reach

China is a rising peer competitor to the U.S. in the world and has clearly demonstrated its ambitions to be an Arctic player. Its interests in the High North range from economic development and scientific research, to seeking to make claims in the Central Arctic Ocean. According to its 2018 Arctic Policy, China declares itself a “Near-Arctic State” – a controversial claim which has bristled true Arctic nations (as attributed by their geography, politics, people, and culture). The Arctic Strategy outlines China’s Arctic interests as economic, environmental, and strategic. China’s navigation and economic objectives as part of its Polar Silk Road (the Arctic dimension of its Belt and Road initiative) includes investment in liquid natural gas development in Russia (Yamal Peninsula), investment in the Northern Sea Route infrastructure, and investment in ports and bases in Iceland and Greenland. China’s predatory economics methodology poses potential challenges for economically vulnerable states like Iceland and Greenland, and its use of economic coercion and control brings significant political-strategic implications. Economic coercion is an instrument of competition. China’s predatory economic behaviour creates economic dependence, which can allow it to achieve a foothold in Arctic. Auerswald views China’s activity in the Arctic Council as a “foot in the door” approach to push for a greater role in Arctic governance. All of these tools are intended to increase China’s access, influence, and claims in the Arctic. In addition, a particular concern is the dual-use purpose of research vessels, ports, and bases creates the potential for future military applications of infrastructure and scientific research.

Russia’s Strategic Behaviour

Russia’s strategic activity in the Arctic is perceived as provocative and is one of the key behaviours that contribute to a regional security dilemma. Russia’s military activities in other parts of the world also contribute to a global strategic competition with Western powers, which tends to colour how Western analysts view Russia’s intentions in the High North. Significant problematic developments that stand out are Russia’s efforts to control the Northern Sea Route, posing a freedom of navigation challenge to the U.S., and Russian advances in offensive missile technology that involves the testing and deployment of systems in the Arctic (in addition to other strategically significant areas, such as in the Kaliningrad enclave).

Russia is a superior Arctic power relative to the U.S. and other Arctic nations. It has a long history of operating in the region and has been revitalizing old Arctic bases and ports and building new ones. It has been modernizing and developing new conventional and nuclear weapons systems, with short- to medium- and long-ranges. As part of Bastion defence to protect strategic assets in the region, Russia is also deploying regional denial capabilities with air defence systems (such as the S-400 air defence missile system) and anti-ship missiles. Resurgent military activities perceived as provocative to Western, particularly NATO, nations involve strategic bomber patrols near the airspace of other Arctic states and exercises through the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom (GIUK) gap. This gap, as an important part of the Bastion defence concept,[3] is to protect strategic assets, such as ballistic missile submarines that patrol in the Barents Sea and Arctic Ocean; in addition to projecting power into the North Atlantic.

In addition to military-strategic developments, Russia is increasing economic cooperation with China in LNG development on the Yamal Peninsula and other projects (LNG 2). This cooperation extends to developing the infrastructure along the Northern Sea Route (NSR), in addition to the construction of an icebreaker fleet, in order to control and administer the NSR. Cooperation with China will continue as long as it serves Russia’s national interests and benefits, but this relationship should be understood as one of circumstance with mutual gains in the interim. How it will play out in the next 10-15 years is undetermined.

Russia’s March 2020 release of Basic Principles of Russian Federation State Policy in the Arctic to 2025 outlines its national interests and long-term goals in the Arctic. The document mostly addresses the economic dimension, scientific research, indigenous issues, and cooperation and dialogue through the Arctic Council; but it does indicate an interest in managing the conflict potential in the region.

The United States and Western Strategic Behaviour

The Arctic has become a new region of military focus for the United States. From a strategic perspective the Arctic is an “avenue of approach” for threats to the North American Homeland. The United States and Canada are evolving North American defence, including modernizing NORAD, in response to the challenges posed by great powers’ new offensive threats that may come over or through the Arctic. Modernization involves evolving defence and deterrence concepts with the continental defence architecture to counter Russian and Chinese advances in long-range missile capabilities, such as hypersonic glide vehicles, next generation cruise missiles, and unmanned aerial systems. US Northern Command and NORAD are proposing a shift in favour of new approaches to deterrence to enhance credibility and affordability. These include deterrence by denial and deterrence by resilience, facilitated through resilient integrated layered systems of sensors and other forms of data collection for all domain awareness, information dominance and decision superiority facilitated through rapid analysis of data by machine learning and artificial intelligence. These processes allow more time for decisionmakers to consider options available to respond to threats to the homeland. The global integration of such systems also involve the sharing of data with allies and partners at a rapid pace, which would facilitate responses to threats in the European Arctic theatre (such as around Norway, the Barents Sea, and the GIUK Gap), as well as in the North American Arctic.

In response to great power, as well as non-traditional threats through, in, and from the Arctic the U.S. military branches have released Arctic strategies. What is interesting about these strategies is that although the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard have released a number of Arctic strategies over the past decade, a new development is that the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Army have released Arctic strategies, where they have never done so before. These strategies reinforce joint force concepts (among the military branches, other government departments, and multinational partners) for the region in order to respond to the various security threats – both traditional and non-traditional – emerging in the Arctic.

The U.S. pivot to the Arctic is not only observed in the North American context, but also in the increase of NATO Arctic exercises and Nordic defence cooperation. NATO exercises in the European Arctic in and around Norway involve both NATO states and (non-NATO) partners, such as Sweden and Finland. Most notable of these is the Trident Juncture exercise in 2018, during which Russia exercised some of its own capabilities in response. NATO behaviour is already a sore point for Russia and Arctic exercises involving the Alliance is also potentially provocative to Russia. Russia perceives increasing NATO activity near its borders as a threat, and views Western militarization of the Arctic as conveying offensive intentions.[4]

Considerations

There is a debate among Arctic analysts whether NATO should become more involved in the Arctic. NATO has no Arctic policy or strategy at this time, but increasing exercises in and around Norway may change that in the future. NATO exercises and the deployment of NATO forces near Russia’s borders is perceived as provocative to Russia, which could increase the potential for conflict in the region.

Is there an “Arctic Exceptionalism” that cannot be affected by geopolitical developments? As presented above, Arctic Exceptionalism defines the Arctic as a zone of peace and cooperation governed by institutions to resolve disputes. This concept assumes that the region would be unaffected by great power competition. However, current developments suggest that great power behaviour can have an impact on stability and security in the Arctic, although the extent is yet unknown. The growing uncertainty creates speculation about possible outcomes given the trajectories of activity by Russia and China. Great power competition may have different impacts on the security and stability in different parts of the Arctic, such as the North American Arctic in contrast to the European Arctic or to the West of the Bering Sea and the Aleutian Islands. Conflict in the region is unlikely, although confrontation and points of escalation may occur in the European Arctic. Russia’s intentions appear to be more transparent and predictable, given the deployment of its strategic forces and defence systems, militarization in the region, and expression of interests outlined in its policies (although its approach to grey zone conflict in multiple domains creates a sense of ambiguity). Russia intends to defend its sphere of influence, deter threats to its second-strike assets, pursue its economic interests and resource development, including controlling navigation in the Northern Sea Route. China, on the other hand, is a wild card, given its predatory economic approach, and ambitions to increase influence through international law and the Arctic Council. It has the potential to drive a wedge between states and become a security threat through dual-use Arctic capabilities in Arctic waters and through investment in infrastructure of vulnerable Arctic nations.

Nevertheless, the Arctic Council will remain a cooperative forum. Whether it will diminish or become ineffectual if the Arctic cooperative regime becomes undermined is uncertain. Actions that would likely undermine the Council and other regional institutions would be those that violate the norms and rules of appropriate behaviour. On the other hand, strategic nuclear and conventional competition could impact the cooperative framework, but that may only apply to the military domain where cooperation and engagement has already been frozen following Russia’s interference in Ukraine. Cooperation on non-military matters may continue alongside different dynamics that emerge in the military-security domain.

The question of the impact of the emergence of new missile technologies and the post-strategic arms control context at the regional level needs to be addressed. As the U.S. and Russia withdraw from arms control and other cooperative regimes, such as the Open Skies Treaty, stability in the region could be affected. Arms control agreements tend to have stabilizing effects that could reinforce cooperation in other areas. A post-ABM Treaty and Post-INF Treaty (and in five years possibly a post-New START)[5] world may affect security and stability in the Arctic through creating conditions for arms races and the increasing deployment of destabilizing systems in the High North, such as offensive weapons technologies and missile defences. Strategic nuclear and conventional capabilities play a significant role in great power competition. The United States, Russia, and China are building new conventional and nuclear delivery technologies that are faster, more maneuverable, stealthy, precise and accurate, which can be considered destabilizing at a global level with regional effects. Thus, the breakdown of arms control leading to arms race behaviour could have an impact in the Arctic, particularly the role of the Arctic in the deployments of offensive nuclear systems and missile defences (particularly Russia’s Northern Fleet’s air- and sea-launched platforms, and the U.S. air and missile defences in Alaska). Russia can target North America while remaining below the nuclear threshold and may attack the U.S. in the event of a conflict elsewhere to prevent or delay deployment to other theatres such as Europe. Shorter- and medium-range systems deployed in Russia’s North can reach targets in the European Arctic (for example, the Barents Sea). In addition to deployment of systems in the High North, nuclear weapon testing in the Arctic has security implications at a local/regional level, risking radiation poisoning of the people and wildlife. These developments create challenges to stability in the Arctic, however, it is difficult to determine the impact that a post-arms control security environment would have on the broader cooperative framework in the region.

Conclusion

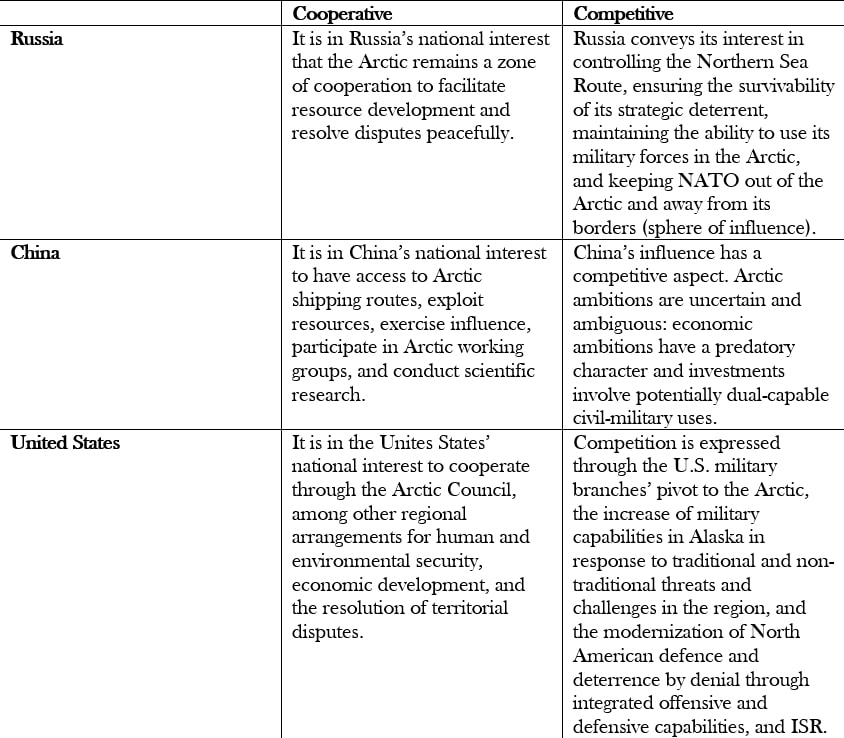

Could a regional security dilemma upset the cooperative framework of Arctic relations? Lackenbauer argues that “the Arctic is neither a region of exceptional cooperation nor conflict apart from the drivers of the greater international system.” This sentiment is echoed in recent statements from the Commander of USNORTHCOM and NORAD. What is global is also regional in the current context of increasing great power competition involving the expansion of the power projection capabilities (military and economic) of the U.S., Russia, and China to the Arctic. Nevertheless, these powers’ national interests demonstrate both cooperative and competitive characteristics. The following table demonstrates that although these great powers prefer security and stability in the Arctic, competition continues to be a significant feature.

Great power competition expressed through an intensifying security dilemma introduces uncertainty and unpredictability in the Arctic. It is possible that an intensive security dilemma resulting from increasing tensions among powers can disrupt notions of Arctic Exceptionalism, but to what extent has yet to be determined. Regional fora offer opportunities to maintain cooperation and dialogue in certain areas, such as the Arctic Coast Guard Forum. Russia’s Chairmanship of the Arctic Council, starting in May, may provide opportunity to enhance dialogue in non-military domains, but the gap in addressing security matters remains. Options for a separate Arctic forum to address military-security matters that would be receptive to Russia are still being explored.

[1] Article 2 outlines the General Provisions of the convention: “Legal status of the territorial sea, of the air space over the territorial sea and of its bed and subsoil.” Although the United States participates in the Law of the Sea conventions and recognizes its international legal status, it has not ratified the treaty.

[2] Among the Arctic-5 circumpolar nations – the United States, Canada, Russia, Greenland (Denmark), and Norway – the Ilulissat Declaration affirms cooperation through UNLCOS and marine protection in the Arctic.

[3] According to Melino et al., “Russia’s military posture in its Western Arctic reflects the Soviet legacy of bastion defense comprised of “concentric circles” designed to protect strategic territory.” They suggest that regional exercises conducted by Russia beyond the Kola Peninsula and Barents sea suggests that Russia may be expanding its bastion defence and sea denial capabilities towards the GIUK Gap.

[4] According to Senior researcher Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Julie Wilhelmsen, Russia “perceives this kind of activity to be a threat to Russia and draw a kind of image of the West being about to surround them and that the West contributes to militarizing the Arctic” to which Russia tends to ascribe offensive intention.

[5] The New START is the last remaining bilateral arms control treaty between the nuclear great powers – the United States and Russia.

Nancy Teeple is a Postdoctoral Fellow at North American and Arctic Defence and Security Network (NAADSN) and Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and Economics of the Royal Military College of Canada.

Comments are closed.