|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In a June interview with La Dépêche du Midi, President Emmanuel Macron said: “We must not humiliate Russia so that the day the fighting stops, we can build a way out through diplomatic channels. I am convinced that it is France’s role to be a mediating power. [..] I think, and I told him, that [Vladimir Putin] has made a historic and fundamental mistake for his people, for himself and for history. Still, Russia is a great nation.”

These passages are interesting because they help to reveal some of the President’s preferences, in particular his understanding of the strategic issues related to the new Russian aggression against Ukraine, his vision of France’s international role and the relationship to be established with Russia.

This is not the first time that Emmanuel Macron wishes to avoid “humiliating Russia,” which has the gift of strongly irritating many of France’s allies in the EU and NATO, as well as Kyiv, but signals a strong conviction on his part, which should therefore be taken seriously. Alexander Lanoszka has already explained here why historical analogies are fallacious, and that as a result the image of France has been greatly degraded. But one question remains: What does “not humiliate Russia” mean in the current strategic context? And how can we understand the origin of this discourse?

What Humiliation?

The French President basically identifies a theory of exit from the crisis. Usually, such a theory can be reformulated according to the following model: if factor X (hypothesis), then Y will occur (outcome) because Z operates (causal mechanism linking the hypothesis to the outcome). In this case, we can reformulate Mr. Macron’s words in this way: if there is no humiliation of Russia, then a diplomatic solution can be found. We can thus immediately see that the causal mechanism, the “because,” is absent from the reasoning: we do not know why the President so strongly associates the absence of humiliation with the success of a diplomatic solution. In Romania, the President reiterated that negotiations with Russia would have to take place at some point, but again without mentioning the conditions that would allow these negotiations to take place. The argument would be more credible if he explained his reasoning because, in the absence of a causal mechanism, it is more an act of faith than an informed basis for a public policy.

Perhaps we need to study the scholarly work on the subject to try to learn more. In the last decade or so, several scholars of International Relations have expanded on the insights of classical realists about the importance of emotions in general, and honor, in the conduct of diplomatic affairs, and have emphasized the role of status. Simply put, status can be defined as the position of an actor vis-à-vis a reference group. Status is also intersubjective: it exists only in terms of how others view it. For cultural and historical reasons, some states may be very attached to having a comparatively high status, expecting honor and recognition from other states. Above all, states may go to war in order to maintain or increase their status. Richard Ned Lebow argues that the majority of conflicts since 1648 have not been initiated for security reasons, but for reasons of status or revenge, while Jonathan Renshon illustrates how the gap between “perceived status” and “desired status” is a powerful driver of conflict. The problem is further compounded, for William Wohlforth, in multipolar systems where hierarchies of power (and associated status) are more ambiguous, potentially leading to states more often seeking to assert themselves within the system. Finally, Joslyn Barnhart has shown that states – and particularly major powers – are statistically much more likely to engage in status-enhancing actions, such as aggression against a weaker state, when they have undergone a humiliating experience (understood as the failure to live up to their international image). A good example of this mechanism is the French invasion of Tunisia in 1881, following the defeat against Prussia in 1870. In this context, one could maliciously argue that, in order to guarantee peace, one should not humiliate Ukraine…

The literature has widely noted that contemporary Russia is a state obsessed with its status, having difficulty accepting its decline, which leads it to aggressive behaviour. Iver Neumann, for example, has shown how, since 1991, the dominant discourse of the Russian elites has been one of superiority over Europe which is presented as declining and on the verge of collapse. This discourse itself is linked to a conspiratorial vision of international relations which perceives any negative event as the result of the hostile action of a West bent on destroying Russia. Limited to certain nationalist circles in the 1990s, these discourses have been consciously promoted by Vladimir Putin’s regime since the beginning of the 2000s in order to create national unity in the face of a designated Western enemy, justifying at the same time the regime’s authoritarian turn. This vision of a Russia under siege by a decrepit and hostile Western enemy is not only a discourse for internal use used cynically by Russian elites too happy to enrich themselves and acquire properties in London, New York and on the French Riviera: it also deeply permeates the Russian security discourse as expressed in military and international relations journals. In this ideological context, it is understandable that Russia can easily feel “humiliated,” as Western countries do not recognize the status to which it believes it is entitled, and that it comes, as mentioned above, to use force to make itself recognized.

This intuitive argument (it is well understood that humiliation can lead to aggressiveness) is probably a valid explanation for the Russian decision to go to war, at least in part, i.e. the temporality ad bellum. But this is not President Macron’s argument, since according to him, avoiding humiliating Russia would lead to a better peace: the temporality is therefore that of in bello. The President, and some of his supporters, have tried to make a distinction between the “Russian people” (who should not be humiliated) and their leaders, but this approach looks like a rhetorical device. Beyond the fact that the discourse of humiliation has been shaped by Russian power circles, as we will see below, it is Vladimir Putin and not the “Russian people” who will decide what is acceptable or not for Russia. This brings us back to the lack of a causal mechanism in the President’s speech: How can the absence of humiliation of “the Russian people” (implying that Vladimir Putin could be humiliated?) lead to a change in Russian foreign policy given the functioning of the current regime?

However, if we do not see the arguments that allow us to establish the logical link as the President does, there are at least two points that plead in the opposite direction: to enter into the discourse of “humiliation” is to take up Russian propaganda and to de facto give Moscow a right of control over Western actions; and this discourse based on emotions eludes the strategic conditions necessary for the establishment of a more lasting peace.

A Revival of Russian Propaganda

In the first place, the discourse of “humiliation” is a reiteration of a Russian strategic narrative centered on a one-way reading of the end of the Cold War. According to this narrative, Western countries did not “respect” Russia’s dignity or its interests. This distortion of history is transparent in the multiple statements of Vladimir Putin, who would cancel the disintegration of the USSR if he could, considers that the end of the USSR meant the end of “historical Russia” or that he is in the lineage of Peter the Great and conqueror of supposedly “Russian” lands. Obviously, this fundamentally neo-imperialist reading is not shared by the countries of the former USSR, which do not consider themselves part of “historical Russia” and understand the collapse as a liberation. The Ukrainian historian Mykola Riabchuk reminds us that the discourse of Ukrainian and Russian “brother peoples,” sometimes held in Western countries, is also a Russian vision of history that denies the reality of the construction of the Ukrainian nation.

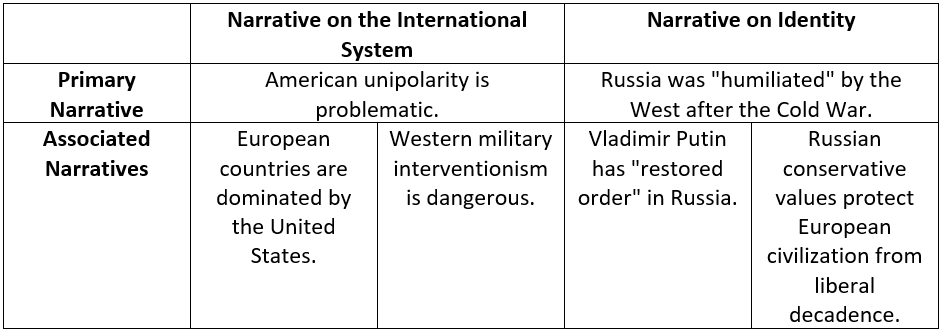

Table 1. The Russian Strategic Narrative (Source: Charles-Philippe David and Olivier Schmitt. La Guerre et la Paix. Approches et Enjeux de la Sécurité et de la Stratégie. Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2020, p. 215).

One might recall that the West, represented at the time by U.S. President George Bush, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, and French President François Mitterrand, was particularly attached to the stability of the USSR for fear of the violence and the risk of nuclear proliferation associated with a sudden collapse. Then, in the framework of a very Russo-centric approach, Yeltsin’s Russia obtained millions in aid from Western institutions, particularly from the European Community, to support a young Russian democracy. No other country of the former USSR benefited from such assistance. The EU signed the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement with Russia in 1994. Then, in 2003-2005, under Putin’s presidency, Russia and the European Union agreed on the terms of a strategic partnership, which was to lead to the creation of four “common spaces”: a “common economic space”; a “common space of freedom, security and justice”; a “space of cooperation in the field of external security”; and a “common space of research and education, including cultural aspects.” In turn, NATO has proposed cooperation with Russia within the framework of the Partnership for Peace program since 1994 and, subsequently, the NATO-Russia Council since 2002. Finally, Western countries have facilitated Russia’s entry into multilateral organizations such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) or the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The entire approach of Western states has been an attempt to “socialize” Russia into multinational institutions, an approach that has failed.

It is clear that if Western countries had wanted to “humiliate” Russia, they could have done it differently. But that is the main issue: the problem with the discourse of “humiliation” is that it is the Russian leaders themselves who define what “humiliates” them. And given the ideological evolution of the regime, it seems that everything that does not correspond to the fulfillment of the desires of the Russian leaders will be experienced and presented as “humiliation” by Moscow. Therefore, adopting a vocabulary of “humiliation” amounts de facto to giving Russia a rhetorical right of review of Western actions in favor of Ukraine, which will always be presented as humiliating. In the current context, one must ask what would really be a “humiliation.” That Ukraine returns to the situation of 23 February 2022 by repelling the invasion? That it recovers the entire Donbass occupied since 2014 (which is the declared objective of President Zelensky)? That it even wants to take back the Crimea annexed in 2014? A military defeat may indeed be vexing, but Russia did unleash an illegal invasion under spurious pretexts: there is no rhetorical or strategic reason to adopt its vocabulary, even if it resonates with certain national political myths.

Indeed, to think that Russia’s (self-declared) “humiliation” is an obstacle to peace misunderstands the strategic preconditions for ending hostilities. In his book How Wars End, Dan Reiter identifies two variables that determine the end of an armed conflict: the first is the belligerents’ information about the balance of power and the adversary’s will, and the second is the belligerents’ confidence that the adversary would respect a possible peace agreement. Applying these two variables to the situation, the stakes are twofold. First, Moscow must be convinced that it will not be able to make territorial gains in Ukraine, that it will not be able to establish military superiority in the future, and that Ukraine will respect a peace agreement. From the Ukrainian perspective, the perspective is reversed: it must be convinced that the balance of power is not dangerously stacked against it, and that Russia will respect a peace agreement. Since Russia has been the regional aggressor since at least 2008, when it invaded Georgia, it will have to give significant proof of credibility and good faith to reassure Ukraine. Thus, if the issue is really to achieve a stabilized situation, the priority should be to allow Ukraine to balance the military balance of power against Russia, and to ensure that Russia respects an eventual peace agreement. Before worrying about Russian emotions, the challenge is to create the strategic conditions that will allow the situation to stabilize. It is certainly important to be alert to the risks of escalation, but there is no strategic justification for using Russian language.

Why Resume the Discourse of Humiliation?

As we can see, there is no logical or strategic justification for the adoption of the vocabulary of a so-called “humiliation” of Russia. It is therefore a question of trying to explain its persistence in French public discourse.

The formula basically raises the question of the interpretation of Russian foreign policy: is Russia primarily seeking to protect itself (and in this case engaging in dialogue helps to improve mutual understanding), or is it primarily an aggressive power seeking to change the strategic status quo (and in this case engaging in dialogue is an invitation to aggression)? The two interpretations have been at odds for the past twenty years, but there were a number of indications that the latter was more plausible than the former: in an academic article published in 2020, we showed that Russian diplomatic practices in multilateral security organizations revealed a political priority given to the restoration of a neo-imperial status, often at the expense of collective security. The February 2022 invasion confirms this analysis, with the so-called “denazification” of Ukraine and the alleged concerns about NATO serving as a poor pretext to justify what is basically “a colonial war under nuclear protection“.

However, some supporters of the first interpretation refuse to draw the consequences of Russian actions, and still seem to believe in the possibility of a good faith agreement with Moscow. The mantra “we must not humiliate Russia,” which is not reserved for the President, is part of this logic: the subtext is indeed to return to cooperation as soon as possible, despite the absence of any empirical evidence to justify this hope with the current regime. This attitude can be explained in at least two ways. First, the end of the Cold War led to a disconnection between the sources of security and the sources of prosperity for European countries: security remained within the transatlantic alliance, but prosperity became dependent on potentially hostile states like Russia. This situation has allowed Russia to “weaponize interdependence” by providing opportunities for economic coercion, but also by creating a network of influential actors with a personal interest (especially financial) in maintaining strong ties with Moscow. In addition to these sectoral interests, Russia has a soft power that is probably underestimated, based on the attraction of the conservative and authoritarian fringe of Western countries for a country fantasized as a model of Christian nationalism, while certain left-wing movements see it as an objective ally of their Americanophobia. Domestic political considerations (especially in the electoral context of the legislative elections) cannot be ruled out for the President: since his main political opponents (Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon) both display pro-Russian positions, he cannot display a position that is too clear-cut on the subject, at the risk of being accused of “Atlanticism.”

Denial of current Russian policy, however, prevents the establishment of a theory of victory and the identification of common interests with our allies. The United States has defined its theory of victory: noting the impossibility of establishing a stable relationship with the current Russian regime, and wishing to continue to focus on containing China, it has concluded that the objective is to weaken Russia as much as possible so that it is no longer a danger to European security. This diagnosis is shared by the Ukrainians, in the first place, but also by a significant number of France’s allies. On the other hand, Paris, Berlin and Rome (in particular), wish to “keep an open channel of communication with the Russian President, in order to encourage him to negotiate a cease-fire and a peace agreement, in the hope – still hypothetical – of stabilizing Ukraine in the long term and restoring the European security order.” As mentioned, there is no indication to date of any Russian willingness to negotiate (on the contrary, there has been a complete radicalization of Russian discourse), and after Chechnya, Georgia and the two invasions of Ukraine, the burden of proof is particularly high for those who think that a reasonable dialogue is still possible. But the risk of European fragmentation on the subject – a major objective of Moscow – is real.

In this context, the presidential statement that France should be a “mediating power” is strange. A mediator is normally a neutral third party, but France is not neutral: it is a member of the EU and NATO, two organizations considered by Ukraine as supporters and by Russia as enemies. The other countries that have made offers of mediation (despite the very limited chances of success due to the ongoing fighting) are more credible in this area: first of all Israel, and to a lesser extent Turkey which, despite its membership of NATO and its arms deliveries to Ukraine, also maintains good relations with Moscow. One might also add that the previous French mediation (on behalf of the European Union) of a war of aggression involving Russia, namely Nicolas Sarkozy’s intervention in the Russian-Georgian conflict of 2008, was widely criticized as having given in far too easily to Russian wishes, which has left its mark and is affecting French credibility in the current process. Here we find the classic French attitude of a “reluctant Atlanticism” (a form of “at the same time” before its time), which has historically only served to annoy our allies without allowing any political gains with our adversaries. One could object that this positioning is also aimed at third-party audiences, for example African, Asian, or Middle Eastern countries that would be happy to see France as an “alternative” partner. But apart from the fact that this discourse can be used by the elites of these countries in a strategic manner in order to flatter French ears that are all too happy to hear it, without necessarily covering up real intentions, it would also be necessary to make an honest assessment of this attitude: is the hoped-for gain with third-party audiences worth the cost of the loss of credibility with our allies and the failure with our adversaries?

Finally, Mr. Macron has his own understanding of the subject. The scientific literature has shown that “fundamental beliefs,” i.e. some strong ideas that decision makers have about the functioning of international relations, are not very sensitive to change and matter in the decision-making process. Brian Rathbun has distinguished two main types of decision makers: realists (like Richelieu or Bismarck) who take a cold view of power relations, and romantics (like de Gaulle, Churchill or Reagan) who believe that their will and talent can overcome all structural obstacles. Mr. Macron is certainly a romantic (and it is doubtful that the mode of election of the Fifth Republic can “produce” anything but romantics), which explains his obsession with establishing a personal relationship with Mr. Putin, in the hope that it will lead to political stabilization. This romantic view of his own talent is accompanied by a fundamentally culturalist and deterministic understanding of what Russia is, which is made very clear in his speech at the opening of the Morozov Exhibition: the President speaks without any irony about “Russian soul” and other romantic-psychological clichés. His words about the “great people” should be clarified, especially in order to find out who he thinks are the “small people,” who apparently deserve to be humiliated.

The combination of a favorable political context and the President’s personal convictions thus explains the prevalence of the discourse of “humiliation.”

Conclusion

The stated desire “not to humiliate Russia” is understandable in the French political context and allows certain actors to flatter themselves by thinking they are “responsible” or “reasonable” in the face of the “emotions” of other countries, but it has a significant reputational and political cost. Indeed, as mentioned by Alexander Lanoszka, the attitude of Paris has greatly reduced the goodwill that might have existed towards the idea of “European strategic autonomy”: the lesson learned by many allies is that France does not take their security concerns seriously and is easily willing to compromise with aggressors, while the United States and the United Kingdom are reliable partners. This situation forces the Élysée to make some welcome clarifications, but they reveal the confusion generated by the President’s words, and mask the real support France gives to Ukraine, both in financial and military terms. We see here the link between domestic and international politics: sacrificing to the discourse that one thinks is politically profitable is sometimes contradictory to the country’s international interests. In politics, the choice of words is important.

The original version of this text was published in French on Le Rubicon. Check it out here!

Comments are closed.