|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The United States’ policy toward Taiwan has been a source of continuing controversy. Amid warnings that Beijing may be preparing to use force against Taiwan by 2027, or even 2025, scholars and analysts are divided about whether U.S. actions are deterring or provoking the PRC. Arms sales and transits of U.S. warships through the Taiwan Strait are par for the course. But declarations of strategic clarity, proposed changes to the name of Taiwan’s de facto embassy in the United States, proposed invitations for Taiwan to join the RIMPAC exercises, and high-level visits of U.S. officials to Taiwan have been far more controversial.

While much of the debate has centered on Beijing’s reaction to U.S. policy, it is no less important to consider Taiwan’s reaction. On the one hand, Raymond Kuo has argued that it is difficult to convince Taiwan’s government to implement an asymmetric defense strategy if there is doubt about the United States’ willingness to intervene. On the other hand, Bonnie Glaser contends that changing U.S. policy to strategic clarity could trigger the PRC to use force, making it important to convey U.S. resolve through signaling.

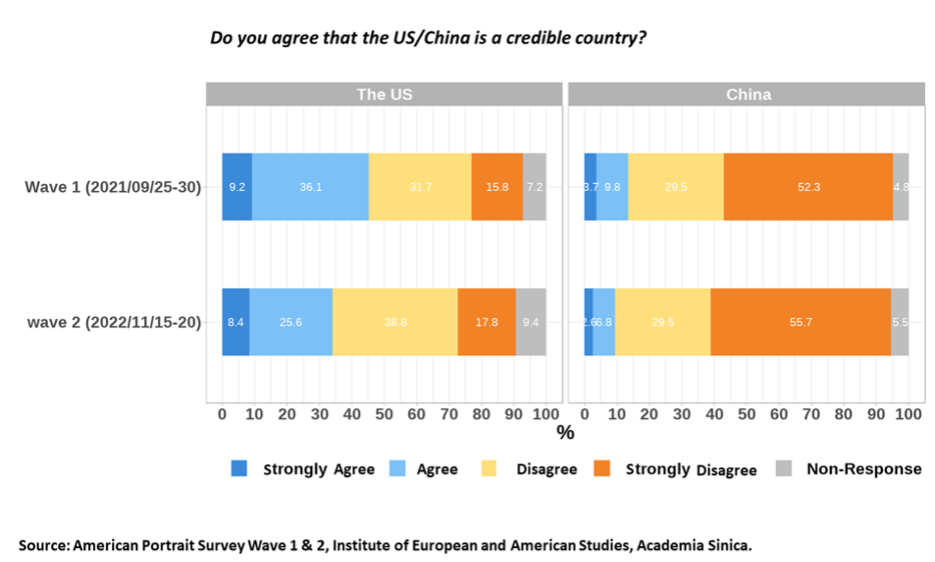

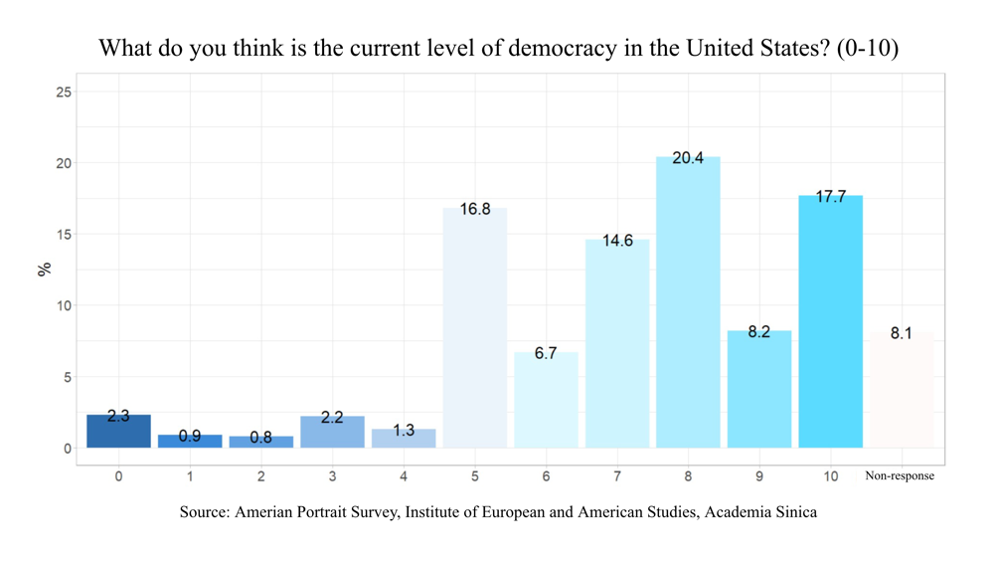

The second wave of the American Portrait Survey (APS) carried out in Taiwan reveals that the United States faces a problem of credibility among the public, but also shows that the public is responsive to U.S. signals. When asked if the United States was a “credible” country, only 34% indicated that they agreed (though this was far more than the 9.4% who agreed with the statement that the PRC was a credible country). The results did not reflect anti-Americanism or a generally negative view of the United States: when asked to rate U.S. democracy on a 1-10 scale, 84.4% gave the United States a 5 or above, and 60.1% disagreed with the statement that the PRC would surpass the United States in the next ten years. Taiwanese respondents have a generally positive image of the United States, but they also harbor significant doubts about U.S. credibility. Even more worrying is the fact that these doubts have grown, even though U.S. policy toward Taiwan has generally been consistent: between the first and second waves of the survey (administered in September 2021 and November 2022 respectively), the belief in U.S. credibility among Taiwanese respondents declined by over 10% (from 45.3% to 34%).

U.S./China Credibility

U.S./China Credibility

U.S. Democracy Level

U.S. Democracy Level

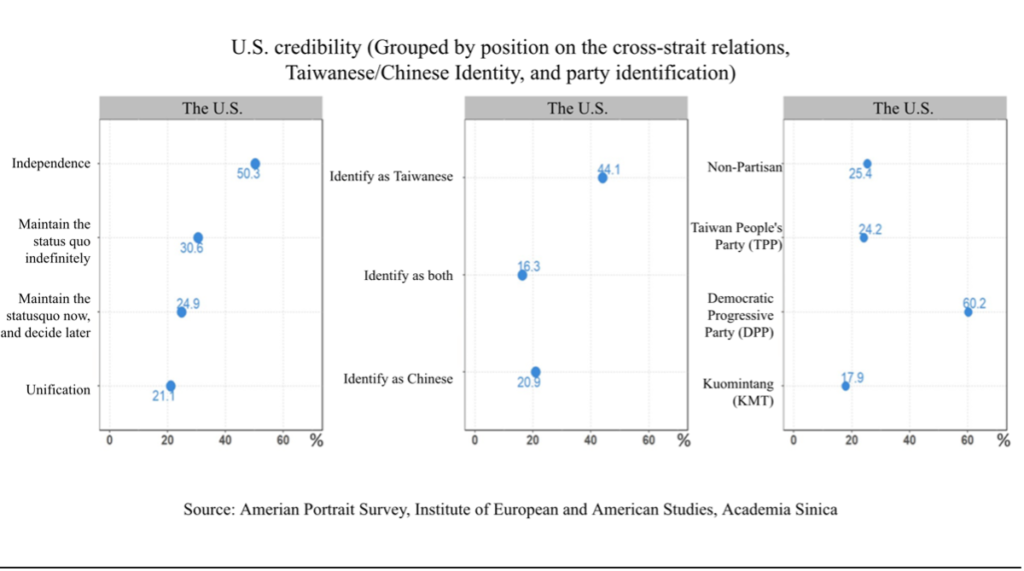

What explains these doubts about the United States? Given that the two waves of the survey were administered before and after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the public may have been responding to misleading comparisons between Taiwan and Ukraine in terms of the United States’ willingness to directly intervene. Moreover, cross-tabulation of the data shows that the fault lines in perceptions of the United States correspond with the other fault lines in Taiwan’s society: independence and unification, national identity, and partisanship. A substantially higher proportion among independence supporters believed that the United States was credible (50.3%) than among unification supporters (21.1%). Among status quo supporters, more of those who wanted to “maintain the status quo forever” (30.6%) considered the United States to be credible compared to those who wanted to “maintain the status quo now and decide later on unification or independence” (24.9%). There is a correlation between how closely respondents lean toward independence and how credible they consider the United States to be. On national identity, a significantly higher proportion of those who identified as Taiwanese (44.1%) considered the United States to be credible compared to those who identified as both Chinese and Taiwanese (16.3%). On partisanship, a substantially higher proportion of DPP supporters (60.2%) believed that the United States was credible compared to KMT supporters (17.9%). Overall, belief in the credibility of the United States tends to be associated with Taiwanese identity, DPP partisanship, and support for independence, while skepticism about the credibility of the United States tends to be associated with Chinese identity, KMT partisanship, and support for unification.

Given that a substantial part of the Taiwan public exhibits doubts about the United States, it is important to consider what types of U.S. signals are effective in Taiwan. Even though there is some characterization of the combination of President Biden’s assurances and the White House’s subsequent denials about a change in policy as “strategic confusion,” evidence from the American Portrait survey shows that the Taiwan public focuses on the assurances: 62% of respondents indicated that a public commitment by the U.S. president to defend Taiwan raised the likelihood of U.S. intervention in Taiwan’s defense. The signaling effect of these visits and presidential statements was even higher than the signaling effect of arms sales, which 56.1% of respondents believed would raise the likelihood of U.S. intervention. Finally, 60.2% of respondents said that visits by high-level U.S. officials raised the likelihood that the United States would intervene in Taiwan’s defense.

Given that a substantial part of the Taiwan public exhibits doubts about the United States, it is important to consider what types of U.S. signals are effective in Taiwan. Even though there is some characterization of the combination of President Biden’s assurances and the White House’s subsequent denials about a change in policy as “strategic confusion,” evidence from the American Portrait survey shows that the Taiwan public focuses on the assurances: 62% of respondents indicated that a public commitment by the U.S. president to defend Taiwan raised the likelihood of U.S. intervention in Taiwan’s defense. The signaling effect of these visits and presidential statements was even higher than the signaling effect of arms sales, which 56.1% of respondents believed would raise the likelihood of U.S. intervention. Finally, 60.2% of respondents said that visits by high-level U.S. officials raised the likelihood that the United States would intervene in Taiwan’s defense.

This last finding seems to be at odds with the finding by Alastair Iain Johnston, Tsai Chia-hung, and George Yin that “respondents overwhelmingly believed that Pelosi’s trip and the large-scale People’s Liberation Army exercises created a serious threat to Taiwan.” But the strongest evidence for their argument comes from a September 2022 survey in which there was a potential issue of compounding in the phrasing of the question: “In August this year, U.S. Congress Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan, and China immediately held large-scale military exercises around Taiwan. Do you think this is a serious threat to Taiwan’s security?” For respondents who said yes, it’s not clear if they thought Pelosi’s visit created a threat to Taiwan, or if they were focusing on the Chinese military exercises. Some of those respondents may have believed that one caused the other, but it can’t be assumed that all of them thought so.

Just before the exercises started, John Kirby, spokesperson for the U.S. National Security Council, accused China of using Pelosi’s visit as a pretext for aggression against Taiwan, and it’s quite possible that some of Taiwanese respondents surveyed by Johnston, Tsai, and Yin believed so as well. The second wave of their survey (from January 2023) resolved the issue of compounding by asking “Do you think Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan made Taiwan more or less secure?” But it appears that this second wave only had a sample size of 576. Using a much larger sample size (1,035), the Taiwanese Public Opinion Foundation found that 52.9% of respondents welcomed Pelosi’s visit, which is consistent with our findings in the American Portrait Survey (which had an even larger sample size of 1,234).

The results of the American Portrait survey indicate that U.S. signals are effective in addressing concerns over U.S. credibility in Taiwan. While scholars and analysts tend to focus on the tradeoffs between threats and assurances in U.S. relations with the PRC, they tend to overlook tradeoffs in U.S. relations with the PRC and U.S. relations with Taiwan. Actions to bolster assurances to Taiwan may erode assurances to the PRC; by the same token, actions to assure the PRC can undercut assurances to Taiwan. U.S. behavior is often read with far more care and scrutiny in Asia for what they may signal and imply than observers in the United States, situated far across the Pacific, may fully realize. Assuming that Taiwan is more constrained due to its relative size and therefore less consequential overlooks the fact that public convictions can affect important steps that Taiwan takes toward conflict prevention, deterrence, and self-defense.

Thomas Christensen, Taylor Fravel, Bonnie Glaser, Andrew Nathan, and Jessica Chen Weiss recently argued that “avoiding war in the Taiwan Strait requires all sides to be deterred.” If this claim is correct, then the U.S.-Taiwan component of this dynamic is no less important than its U.S.-PRC leg. A Taiwan that is confident about U.S. support—especially in the face of an unprovoked PRC attack—is more likely to implement the new asymmetric defense strategy that the United States now encourages. Otherwise, Taiwanese who will bear the brunt of any aggression may feel less sure about moving away from more familiar, traditional approaches to defense despite their growing limitations in the eyes of experts. Such conditions must be considered as part of efforts to avert conflict and avoid the use of cross-Strait relations as a cudgel in U.S. domestic politics that could spark a crisis.

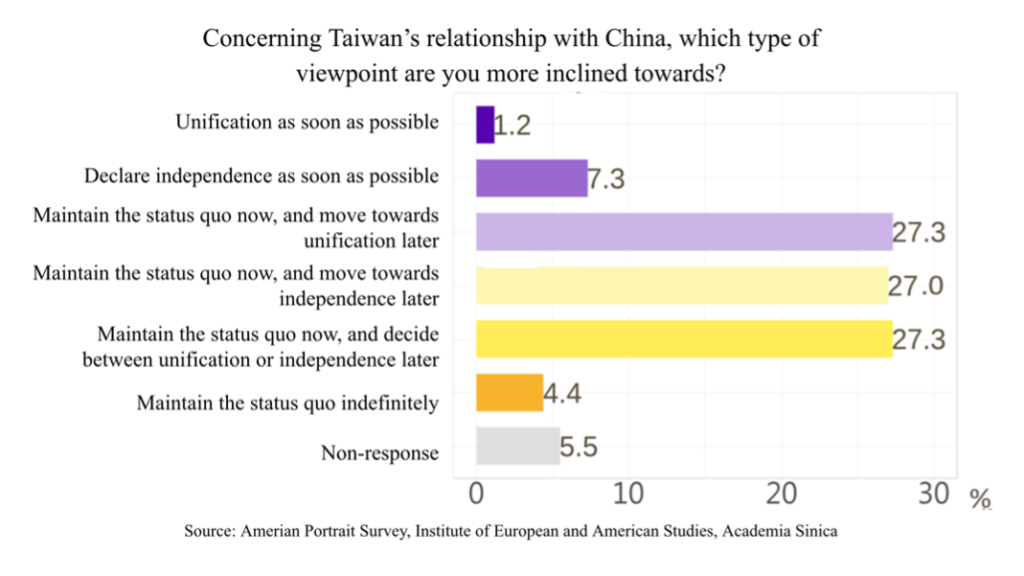

The fact that over 80% of Taiwanese steadfastly prefer the status quo in some form should allay concerns about assurances prompting Taiwan to incite Beijing through a unilateral declaration of independence or some other form of adventurism. Preference for the status quo has remained stable across the population for over a decade, as shown in repeated polling conducted by the Election Study Center on behalf of Taiwan’s cabinet-level Mainland Affairs Council. This orientation is probably as close to a consensus as possible in a democracy, particularly one as lively as Taiwan’s. Taiwan today differs substantively from the early 2000s, when less bridled populist nationalism, a less institutionalized political system, and the uncertainties associated with democratization may have created more cause for worry. Taiwanese treasure their autonomy, but they recognize the costs of confrontation with the PRC, whatever the outcome. The strength and clarity of these widely shared sentiments will restrain any Taiwanese politician from behaving recklessly. Any politician or political party that goes against the prevailing position will be held accountable by the Taiwanese public, which is not afraid of making the strength of its views known.

Giving Taiwan confidence without triggering the PRC to use force or coercion presents the United States with a dilemma. This tension will remain a persistent feature in Washington’s relations with Taipei and Beijing so long as the PRC insists on a right to use force to exert control over Taiwan and makes active preparations to do so. Since the abrogation of the U.S.-Republic of China Mutual Defense Treaty in 1980, successive U.S. administrations approached the matter through a studied “strategic ambiguity.” That is, to simultaneously deter Beijing and Taipei from engaging in provocative behavior by convincing both sides of the uncertainty over U.S. intervention in a potential Taiwan crisis. Given Taiwan’s maturing democracy, a cautious Taiwanese electorate to which politicians must answer, as well as a PRC whose capabilities and appetite for risk are growing, asking whether the old U.S. approach to “strategic ambiguity” remains fit-for-purpose is both reasonable and relevant.

Managing the evolving situation across the Taiwan Strait means actively adjusting to evolving material and political circumstances. The United States’ own changing capabilities as well as domestic and international commitments too are important considerations in this regard. So far, it seems that the United States has chosen to navigate that dilemma by resisting formal changes in declaratory policy while informally calibrating policy implementation, such as by providing verbal assurances and increasing engagement with Taiwan as permitted under the Taiwan Relations Act and supplemented by the Taiwan Travel Act.

Sending clear but limited signals of assurance simultaneously to Taipei and Beijing seeks to square the circle by recognizing that while Washington can help shape key conditions, it is unable to fundamentally change minds in either Taiwan or the PRC. Imperfect as this approach may be, it can buy time for Taiwan and the United States to update their ability to more effectively deter the PRC from escalating coercion and the use of force. This position may also help Washington to demonstrate the seriousness of its commitment to maintaining peace, stability, and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific and beyond to allies, partners, friends, and others.

Technical Note

The second wave of the American Portrait Survey (APS) was sponsored by the Institute of European and American Studies (IEAS) at Academia Sinica in Taiwan and conducted by the Election Study Center (ESC) at National Chengchi University in Taiwan. It was based on a sample of 1,234 Taiwanese adults, who were interviewed via landline (708) and mobile phone (526) between November 15 and November 20, 2022. With a 95% confidence level, the maximum possible random sampling error is 2.79%.

James Lee is an assistant research fellow at the Institute of European and American Studies at Academia Sinica in Taiwan. His research in strategic studies focuses on U.S. foreign policy and the security of Taiwan.

Ja Ian Chong is a Non-Resident Scholar at Carnegie China. He works on security issues in East Asia, including coercive diplomacy, external intervention, contentious politics, and major power competition. Chong has published widely on these topics.

Hsin-Hsin Pan is associate professor of sociology at Soochow University in Taipei. Her research interests include political sociology, survey methods, and cross-Strait relations.

Chien-Huei Wu is Research Professor in Institute of European and American Studies, Academia Sinica, Taiwan. His research interests cover EU-Asia relations and US-Taiwan-China relations. He has published Law and Politics on Export Restrictions: WTO and Beyond (CUP 2021).

Wen-Chin Wu is an associate research fellow of the Institute of Political Science at Academia Sinica, Taiwan. His research interests focus on political economy, comparative democratization, and Chinese politics. He has published in China Quarterly, International Studies Quarterly, Political Communication, among others.

Comments are closed.