Analysis of Donald Trump’s plan for Armenia and Azerbaijan

On 8 August 2025, Donald Trump welcomed Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev and Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan to the White House and assured them of his support for the process of resolving the conflict between the two countries, which has been ongoing for more than thirty years.

The two former Soviet socialist republics have clashed several times during this period over control of Nagorno-Karabakh, a mountainous region then populated mainly by Armenians and enclaved within Azerbaijan. In September 2023, the Azerbaijani army regained full control of this enclave and its capital Stepanakert, renamed Khankendi and reintegrated into the Republic of Azerbaijan. Its Armenian population was forced to flee to Armenia, but the end of this armed conflict raises several questions that continue to fuel tensions between the two countries: the fate of Armenian prisoners of war, the preservation of cultural heritage in the region, the repopulation of the region under the authority of the Baku government, and the reception of Karabakh refugees in Armenia.

While war was the most decisive factor in the political and geopolitical landscape in the region, lasting peace is now the goal that all these actors are calling for, in line with the principle of ‘peace through deal-making’ dear to the President of the United States. But the construction of this peace also faces conflicting interests. In this hotspot, the objectives of regional and external actors who claim to support appeasement in the Caucasus will be analyzed.

Karabakh, Aliyev’s government’s new showcase

Firstly, it is important to consider the conflict itself and its resolution. On the Azerbaijani side, it is said that the issue has been closed with the reintegration of the Karabakh region, while on the Armenian side, there is regret at the lack of measures in favour of the civilian population, particularly with regard to the thorny issue of the ‘right of return’. Indeed, a large part of this population living in the breakaway republic of Artsakh (the Armenian name for Nagorno-Karabakh) already resided there before the first war in 1988. Conversely, the Azeri populations who were exiled to other regions of Azerbaijan after the Armenians took control are now being encouraged to return to the region, even though most Azeri villages have been abandoned for three decades.

Through incentives and infrastructure development, President Aliyev is attempting to make the region attractive to his citizens, offering them, among other things, the opportunity to live in new towns built by the government at low cost, in order to boost his popularity. Aliyev’s goal is to turn the page on the war, despite accusations of ethnic cleansing, and he is calling on Armenia to amend its constitution by removing references to Artsakh and to end the OSCE Minsk Group, which was a platform for a peace process monitored by Russia, the United States and France. However, President Aliyev’s demands continue to fuel resentment in Armenia, which is torn between the desire to find lasting peace and the trauma of this lost land.

The political crisis in Armenia

Pashinyan’s government is indeed under pressure. The Prime Minister, who came to power following a velvet revolution in 2018, is now in open conflict with the parliamentary opposition, as well as with the Armenian Apostolic Church, which wields moral authority among the population, and with Samuel Karapetian, the country’s richest man and owner of the largest energy company. The Prime Minister claims to have escaped a coup organized by Karapetian and Bishop Bagrat Galstanian, who is the spokesperson for opponents of the peace process with Baku. The rift between the government and these actors is also very deep and divides Armenian society. Against the backdrop of this new divergence lies an older, more geopolitical divergence between those who favour closer ties with the West, embodied by Pashinyan, and those who are nostalgic for the very strong relationship with Russia.

Indeed, following the withdrawal of Russian peacekeeping troops from the Lachin corridor between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh in 2023, Yerevan went further than ever in its divorce from Moscow, indirectly linked to Vladimir Putin’s strategic isolation since 24 February 2022.This Russian withdrawal, deplored by Armenia, has been interpreted by experts as a blank cheque given to Ilham Aliyev to wage the latest war, for fear of damaging their relations with him. For example, Armenia suspended its participation in the Collective Security Treaty Organisation, a political-military alliance led by the Kremlin, and passed a law in parliament in favour of a potential application for membership of the European Union. This move by the Armenian government revealed Russia’s loss of influence in the South Caucasus, a region it considers its ‘near abroad’.

Normalisation(s)?

However, this normalisation seems to depend on normalisation between Yerevan and Baku, as Turkey remains loyal to its alliance with Azerbaijan, despite certain fundamental disagreements, particularly on the Middle East. For its part, Armenia is trying to capitalise on a project called ‘Crossroads of Peace’, which would open the borders between the countries of the Caucasus. This seems necessary, given that Georgia, which had remained neutral in this dispute and was therefore a transit route for many, appears to be increasingly unreliable due to the policies of its new government, which is not recognized by part of the international community.

“Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity”

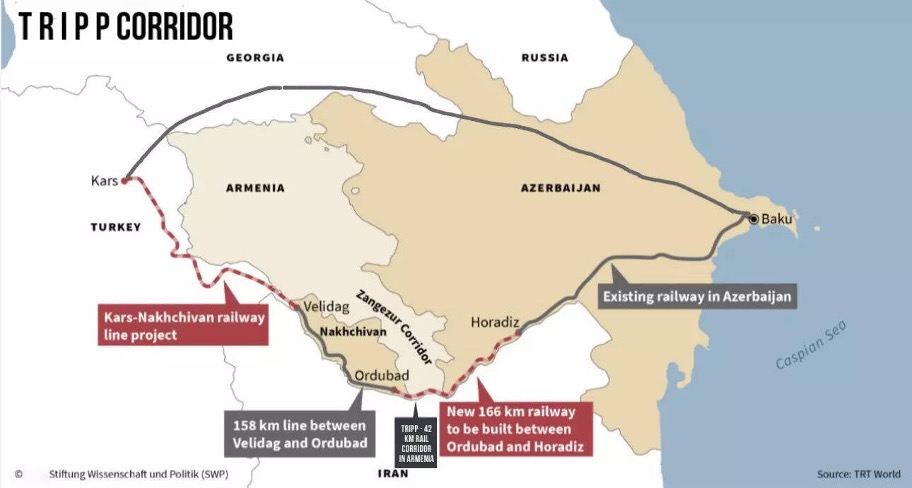

One of Azerbaijan’s conditions for signing a definitive peace agreement with Armenia is the creation of a corridor that would cross the Syunik region in southern Armenia and connect the autonomous region of Nakhchivan to the rest of Azerbaijan. At present, Azeris from Nakhchivan must pass through Iran to reach it. Furthermore, this autonomous region borders Turkey for several kilometres: the dream of Azeri nationalists is to link these two parts of the Turkic world. Azerbaijan is already Turkey’s leading energy partner, which is supplied by Georgia. These corridor projects are considered dangerous for the Armenians, firstly because they would undermine their territorial sovereignty, and secondly because the Baku government has already shown that it cannot be trusted. Armenia is keen to hold on to its southern region of Syunik, as well as its narrow border with the Islamic Republic of Iran, which remains a significant economic partner.

While the Armenian Prime Minister wants above all to prevent Azerbaijan from occupying this narrow strip of land a few kilometres wide, which would give it access to Nakhichevan and the border with Turkey, President Aliyev wants to avoid a corridor controlled by the Armenians, who could impose transit fees on their territory. Aliyev calls this corridor the ‘Zangezur corridor’, referring to the Azeri name for the Syunik region, which is considered provocative by the Armenian side, as this name disregards Yerevan’s sovereignty over this valley.

This is where President Trump comes in. His goal: to thwart Russian and Iranian influence in the Caucasus. The 47th president is continuing his project of making peace at any cost through deals, and no longer hides his intention to win the Nobel Peace Prize for this reason. Among the six or seven peace agreements he claims to have established, he includes the one between Armenia and Azerbaijan, even though the countries have not been in armed conflict since 2023. Trump has thus offered to act as an intermediary for the two leaders of the South Caucasus. He is proposing an American long-term lease on the Syunik road, renamed TRIPP, for Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity, which would connect Nakhichevan to Baku. This American control would last for a hundred years, but raises several questions: first, is Armenia’s national sovereignty truly respected? Second, does it put an end to Baku’s ambitions and establish stable peace? Finally, does this corridor open up the region, where many borders remain completely closed in the absence of genuine diplomatic normalisation?

A geostrategic turning point to open up the region

Armenia and Azerbaijan must take advantage of this new situation to transform their bilateral relations. For a long time, these two countries have been in Moscow’s orbit, which has continued to fuel tensions between them for decades. Armenia has always been highly dependent on Russia because, unlike Azerbaijan, it does not have its own energy resources. The latter has maintained its historic relationship with Turkey, even though disagreements on certain issues are becoming increasingly vocal (notably on the relationship between these two countries and Israel, Ankara’s strategic rival but Baku’s unfailing military and energy partner). Georgia, which maintained cordial ties with both countries, is itself facing unprecedented instability, forcing everyone to rethink relations throughout the region. Iran was Armenia’s traditional ally by default, due to its rivalry with Azerbaijan. Now greatly weakened by its war against Israel, Tehran views the TRIPP project with suspicion, in an area that was influenced much more by Moscow than by Washington.

But the United States is not a sufficient partner, and Armenia and Azerbaijan need to develop partnerships in Eurasia. This is where China appears as a new option: unlike Russia, it does not have a bad image with the respective governments and is offering to include these countries in its new Silk Roads. Azerbaijan is seen as essential in the establishment of the famous Trans-Caspian corridor, also known as the Middle Corridor, which connects the China Sea to Europe via Kazakhstan, the Caucasus (bypassing Armenia) and Turkey.

Armenia and Azerbaijan, like Turkey, participated as dialogue partners in the Tianjin summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, which brings together China, Russia, India, Pakistan and Iran, among others, and seeks to offer Asian countries an alternative alliance to American hegemony. It was in this context that Nikol Pashinyan met with Xi Jinping. Between the American TRIPP and dialogue with the East, Armenia and Azerbaijan seem, in various respects, to be trying to play on several fronts to ensure their geostrategic transition. Yerevan has also taken advantage of the end of the war to forge relations with the SCO countries, particularly India, with which it has already been close in recent years. It should be noted that Yerevan has established diplomatic relations with Pakistan, which was the only UN member state that did not recognize the independence of the Caucasian country due to its support for Baku. Armenia is now recognised by the entire international community.

Rapprochement with the EU

And what about the European Union? The EU is an important partner for both countries, including them in its neighbourhood policy, but opting for a relationship tailored to each government. While the relationship with Azerbaijan is mainly commercial, due to Baku’s energy exports to Europe, Armenia is considered an essential relay in the region, particularly since Georgia’s new government seems to be abandoning its desire for EU integration. The EU has therefore had a civilian mission in Yeghenadzor, Armenia, since 2023. The European Union has always supported the peace process between the two countries and welcomed the efforts made by Yerevan and Baku during the meeting at the White House.

The European Union also encourages the normalisation process between Azerbaijan and Armenia, as well as between Armenia and Turkey. Some EU member states have historically been more supportive of Armenia, particularly France and Greece, while others have generally shown closer ties with Baku.

What does the future hold for Europe’s presence in this region? In Armenia, the government wants to show its desire for closer ties with Europe through a bill passed by parliament in March 2025, ‘initiating the EU accession process’, although this is not binding at the diplomatic level. No official application for membership has been submitted, unlike Georgia, Ukraine and Moldova.

While this pro-European stance by Pashinyan’s cabinet is unprecedented for an Armenian government, it remains subject to nuances. Firstly, Yerevan has also developed numerous ties with India and China, as well as with certain Gulf countries; secondly, its domestic policy plays a very important role in this regard. Indeed, in June 2025, the country will hold parliamentary elections, which will certainly be decisive in determining Armenia’s direction. Pashinyan is currently relatively unpopular, particularly because of his disputes with the Apostolic Church, but he is also exposed to disinformation campaigns by Russia, as well as in Moldova in the run-up to the September 2025 elections. If he is re-elected as Prime Minister, he will also have to put to a referendum the question of constitutional changes demanded by Azerbaijan for a peace treaty, which is far from certain. All these domestic political issues make Pashinyan’s government highly vulnerable to foreign interference and could, in the future, weaken Euro-Armenian relations.

In conclusion, it could be said that although Armenia and Azerbaijan are on the verge of concluding a lasting peace, the situation remains very tense. The next key milestone for the future of this region will be the Armenian parliamentary elections in 2026, which are likely to be marked by intense political tensions, unprecedented attempts at interference and considerable uncertainty among the population. The fate of neighbouring Georgia is equally uncertain, and seems to demonstrate that lasting regional stability is not on the cards for 2025 or 2026. However, Armenia’s efforts to normalise relations with its western and eastern neighbours are not insignificant. Nor is the decline of Russian influence. Moscow has undoubtedly not given up on this region, which it considers highly strategic due to its geography, history and trade links. For Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Turkey, the Caucasus is gaining strategic importance and contributing to its consolidation in the great geopolitical game, while domestically, the government is facing new challenges.

The diagnosis for Westerners is ambivalent: on the one hand, peace is being encouraged, including following Trump’s plan, and Russia seems to have backed down; on the other, this situation has favoured the emergence of Turkey as a new regional power and Azerbaijan as a strategic partner, even though the latter has shown an unprecedented authoritarian retreat and put an end to any multilateral solution to the conflict with Armenia.

As things stand, Armenia appears to be the EU’s new privileged ally in the region, at a time when Georgia is drifting towards authoritarianism and falling back into Vladimir Putin’s beloved ‘near abroad’. It remains to be seen whether this trend is sustainable and whether the promises made by Donald Trump through his famous TRIPP will be followed by real diplomatic progress.

Comments are closed.