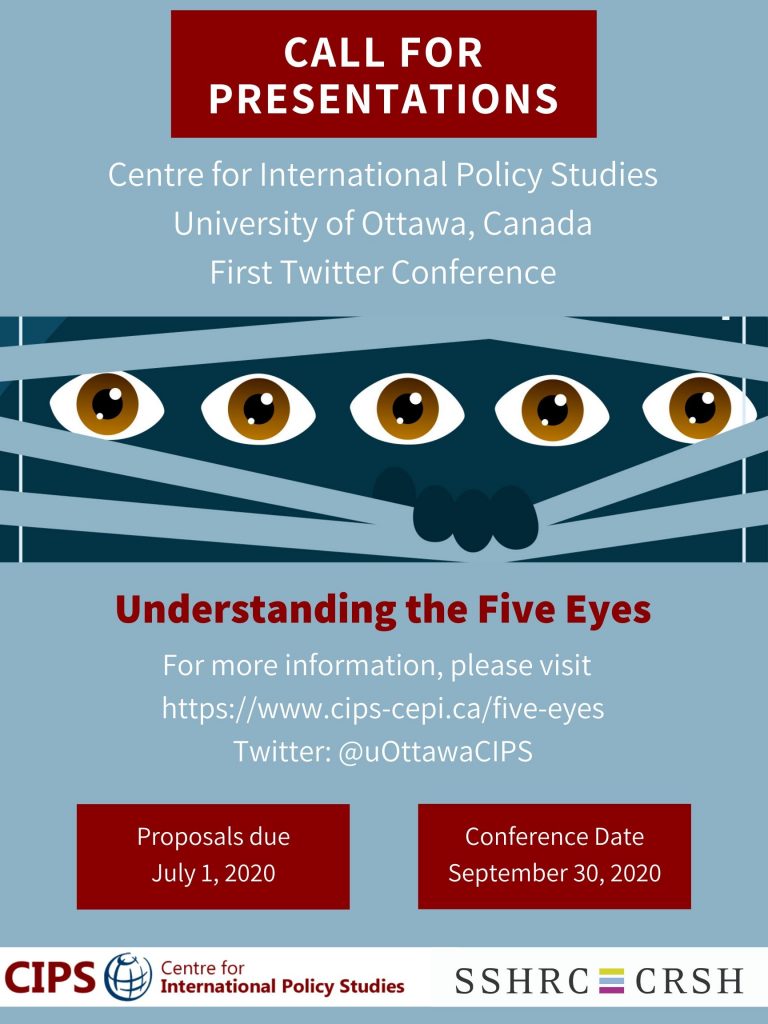

The term Five Eyes typically refers to a unique signals intelligence pooling club of three or four-letter acronymed agencies from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States. But FVEY, as it is also known, is now also attached to a large and growing number of “special relationships” and transgovernmental policy networks that bind these five states in virtually all areas of defence, intelligence, and security.

Network for Strategic Analysis (NSA)

| Pavillon Charles-De Koninck, Bureau 5458, 1030, avenue des Sciences-Humaines

Université Laval | Québec (Québec) G1V 0A6 Canada

+1 613 533-2381 | info@ras-nsa.ca

+1 613 533-2381 | info@ras-nsa.ca

Comments are closed.