The types of conflict states aim to deter have evolved since the Cold War, presenting new challenges each time. Deterrence theory became popular during the Cold War, with nuclear capabilities dissuading the United States and the Soviet Union from engaging in direct conflict. After the Cold War, and especially during the early 2000s with the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, western states struggled to navigate how to deter terrorist attacks, especially by non-state actors. Around 2010, the focus on intense large-scale counterinsurgency and counterterrorism operations began to wane, and attention shifted to the return of great-power competition.

Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea have increased the rate at which they challenge the rules-based international order through provocative and harmful actions that do not cross the threshold as actions of war. Most of their actions are conducted covertly with the aim of disrupting western hegemony while avoiding overt acts that could result in criticism or retaliation. Aggression against western countries is increasing, and the ambiguity of these threats challenges traditional deterrence concepts. While traditional deterrence theory and practices are thoroughly understood, there is a lack of consensus amongst academics, practitioners, and international law on what constitutes aggression or appropriate response in the grey zone. The lack of a concrete understanding of the grey zone makes it harder to develop theories and policies for grey zone deterrence. This paper will review the literature on basic deterrence theory, definitions of what the grey zone is and is not, the leading concerns of present grey zone conflicts, the challenges of grey zone deterrence, and conclude with several ways to deter grey zone conflict.

Deterrence Theory

At its core, deterrence is about preventing war. It is not a long term solution to a hostile security environment but takes a threat-based approach to convince opposing states that aggressive action is not in their best interest. Deterrence can be conceptualized in a few ways: the first is by deterring states through denial or through punishment. Deterrence by denial occurs when a state has robust capabilities that an enemy attack would not be able to overcome or that the impact of the attack would be significantly diminished or delayed. Deterrence by punishment occurs when an aggressor state chooses not to attack because they believe that even if they achieve their objective, they would be subject to punishment such as sanctions or a counter-attack that would be more costly than what was gained from the initial attack. In the perfect scenario, a state’s defence capabilities would be strong enough to achieve both, but this is not the case for many states.

An alternative but complementary way to conceptualize deterrence is as a pyramid. As a pyramid, nuclear deterrence is at the top, followed by punishment through armed forces and traditional hard power. Next would be deterrence by denial. Last is extended deterrence, where a state is able to deter threats because one or more other states would defend it. A prime example of extended deterrence is NATO’s Article 5. Unfortunately, nuclear deterrence, deterrence by punishment, and even extended deterrence have a limited effect when it is hard to determine the nature of foreign attacks in the grey zone.

What is the Grey Zone?

Grey zone actions are often interchangeably labelled as “hybrid” or “unconventional” warfare. Grey zone conflict is any confrontation that is beyond standard and diplomatic competition but that does not cross the threshold of war. It is the area between distinct war and peace. It often occurs through various domains such as economic, financial, cyber, policy, and others, where conventional conflict is focused on the strategic use of violence. It can also be conducted by states, non-state actors, or proxies. Grey zone conflicts can incorporate conventional and unconventional approaches. Grey zone attacks are often intentionally covert, which makes it difficult to attribute blame, and they are usually just below the threshold to warrant a military response. Thus conventional deterrence does not work when it is unclear who conducted the attack, what the intention of the attack was, and at what point an attack goes beyond the grey zone and is damaging enough that a violent response is appropriate.

Grey Zone vs. Hybrid Warfare

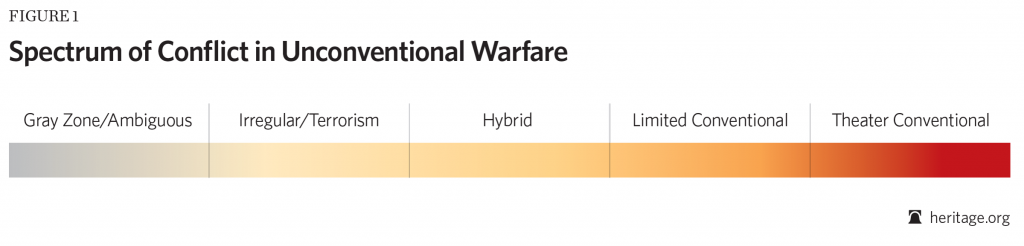

Despite the conceptual overlap of the “grey zone” and “hybrid warfare,” they are not synonymous. Hybrid warfare is the combined use of conventional and unconventional tactics that do cross the line of warfare. Some of the hybrid tactics used, such as disinformation, may be in the grey zone. Grey zone conflict is only the tactics that do not cross the line of formalized state-level aggression. Hybrid warfare is focused on events at the tactical level, while the grey zone encompasses the long-term strategic considerations of international competitions. Figure 1 from Frank G. Hoffman provides a visual representation of the spectrum of conflict and clearly demonstrates a difference between the grey zone and hybrid warfare, where both fall under the spectrum of conflict in unconventional warfare. This is why unconventional tactics of aggression are often discussed as a means of grey zone conflict and hybrid warfare.

Contemporary Grey Zone Aggressions

Grey zone conflict has become a topic of interest predominantly because of the actions of Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea over the past ten years. All four states have used disinformation and engaged in cyber-attacks through hackers and proxies to penetrate security systems and cause low-level damages. Russia and China have both made creeping territorial expansions but through different means. In 2014, Russia used disinformation to aggravate tensions in Crimea, leading to its annexation. In 2015 and 2016, a Kremlin-linked hacker, Sandworm, infected Ukrainian utilities with malware and left thousands of Ukrainians without power. In 2017, Russia was also linked to a virus that rendered the IT system of Maersk, a Danish shipping company, useless for a week, costing 300 million USD in losses. This is in addition to countless cases of disinformation and media control targeted against western alliances and NATO operations. The strategy is labelled as “simmering borscht,” where Russia tries to expand its influence without triggering a western response.

Since 2014, China has been building bases on islands in the South China Sea to extend and solidify its territorial claims. China’s behaviour has been referred to as the “salami-slicing tactic” where it slowly erodes the international order and norms, divides alliances, and tries to assert its preferred interpretation of existing international laws. China’s use of fishery and maritime security to expand its control of the South China Sea through deliberate and deniable acts of aggression are the perfect example of grey zone conflict. The ties between Chinese companies and the government have also proven to be a point of grey zone conflict with Huawei leading to concerns amongst the Five Eyes. Tensions with China have contributed to a detainee stand-off with Canada holding executive Meng Wanzhou and China holding Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor.

While Iran and North Korea are not recognized as key players in great power competition, they have been noted for increased grey zone aggression through political, economic, cyber, and military actions since 2016.

Challenges of Grey Zone Deterrence

The paradox of grey zone conflict is that it is more prominent when all-out war is successfully deterred. This is why grey zone conflict was also frequent during the Cold War. The first challenge is that the grey zone is inherently ambiguous, and deterrence, especially deterrence by punishment, depends on clearly defined responses to identifiable attacks. Attacks on civil society and that are below the threshold of NATO’s Article 5 leave it unclear if the solution should be state-on-state military actions. Furthermore, traditional deterrence is based on direct and violent attacks, usually targeted at military infrastructure, or resulting in direct violence against civilians. Yet, damage to power grids and cyber networks runs the risk of being just as damaging. Extended interruption to power and cyberinfrastructure could result in the loss of life in the case of hospitals, traffic control, and food safety, and can result in significant financial damage as economies are put on pause. A recent cyber-attack on a water supply facility in Florida demonstrates the vulnerability of essential public sector services. Cyber-attacks are particularly difficult to deter because they are conducted by state-level actors, non-state groups, and individuals, making it hard to trace and attribute blame in a timely manner. They are also aimed at private and civilian sectors more frequently than conventional military aggression, requiring coordination between the attacked organization and their national security services.

Democratic states that choose to play by the rules-based international order are at a disadvantage when it comes to grey zone conflict. States like Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea have highly centralized governments that are able and willing to employ propaganda, target civilian entities, push boundaries on legal norms, and employ non-state proxies to their advantage compared to liberal-democratic states. Aggressor states use democratic states’ commitment to international norms and bureaucratic approval processes for retaliation to their advantage, reducing the impacts of deterrence by punishment. Democratic states are in a tough spot because these bureaucratic procedures and the importance of civilian oversight of the military uphold the central values of their liberal identity.

What Deterrence Looks Like in the Grey Zone

Just because deterrence is more challenging in the grey zone does not mean it has no value. Politicians and academics need to be cognizant of the limitations of grey zone deterrence and how to shift their strategic approaches. Clearly defined red lines for acts of aggression, particularly in the case of cyberspace, and triggers for escalation of force for non-military attacks can aid in grey zone deterrence by punishment.

In the case of conventional grey zone aggression, rapid reaction forces are one of the best hard power deterrents the West could further invest in. In the case of Russia’s annexation of Crimea – where disguised paramilitary and military forces were used – rapidly deployable troops would have raised the stakes for Russia’s actions and been able to respond faster the second Russia crossed the line from grey zone to hybrid warfare. When it comes to cyber-attacks, retaliatory cyber-attacks or even the use of the military when a line is crossed could be effective. The link between cybersecurity and conventional military responses is poorly defined, which presents a window of ambiguity and opportunity for attackers. Furthermore, the secrecy of offensive cyber capabilities undermines their deterrent value, as conventional deterrence partially relies on a show of strength so the enemy can understand the potential consequences for their actions.

Deterrence by denial, however, seems to be the most strongly advocated route to improve grey zone deterrence. The first part of this is through enhanced investment and training in cybersecurity to mitigate vulnerability to attacks. The second part of grey zone deterrence by denial is resilience. This means the resilience of cyberinfrastructure as well as societal resilience. At the 2016 Warsaw summit, NATO presented seven baseline requirements for civil preparedness:

- Assured continuity of government and critical government services;

- Resilient energy supplies;

- Ability to deal effectively with uncontrolled movement of people;

- Resilient food and water resources;

- Ability to deal with mass casualties;

- Resilient civil communications systems;

- Resilient civil transportation systems.

Recommendations for Canada

Canada has regularly employed methods of hybrid warfare during its interventions in failed and fragile states, even if it is not described that way. Canada’s interventions employ civilian and military co-operation as well as economic and political elements that involve training, interacting with, and influencing security forces, politicians, and the public.

Democratic states like Canada tend to perform well to immediate security threats, but poorly to grey zone threats that are below the threshold and do not trigger public concern that leads to political action. While we are not at war, there is a lack of public knowledge that Canada is targeted daily by grey zone attacks against its cyber space, public information, military, and even against Canada’s physical territory.

Canada must expand its intentional and strategic engagement with hybrid warfare, and prepare for grey zone threats. The first step to enhancing our defence against grey zone conflict is understanding it. The literature shows that we need a clearer definition of the grey zone and how states ought to respond. This should be supported by bodies like NATO. Canada and its allies must understand what they are deterring, where they draw the line for aggressive actions, and how they will respond. Canada must clearly define and draw a line for grey zone aggression for domestic purposes. Canada should also work within NATO to build a consensus on what kinds of attacks the alliance will responded to under Article 5, and how the alliance will respond when an act of aggression does not cross the threshold of war.

One of the most important aspects of deterrence by punishment is a timely reaction. Canada must continue to ensure its military is up to the task for rapid response when an act of aggression goes beyond the grey zone. A larger gap exists in Canada’s retaliatory, or offensive cyber capabilities. Canada should develop its cyber security and defence capabilities to conduct counter attacks – a way of retaliating through the same means, and remaining in the grey zone.

Finally, the most peaceful and reassuring way to protect Canadians from grey zone aggressions is through denial and resilience. Because grey zone conflict can be targeted at anyone, the critical and challenging part of denial and resilience are that they require extensive engagement with the general population and private sector. The Canadian government will need to regulate and promote higher standards of cyber security and resilient infrastructure in the public and private sectors. Crisis management will need to occur between cabinet ministers and CEOs. Public education campaigns for how to detect disinformation and cyber vulnerabilities will also be important. Grey zone conflict requires a whole-society approach for successful deterrence and to keep aggression in the grey zone and away from all-out war.

Comments are closed.