Several articles published in September 2025 revived alarmist positions on threats to Canada’s sovereignty. Their authors paint a bleak picture of a Canada unable to control its Arctic territory and facing aggressive China and Russia, which have great ambitions for its territory. These grim scenarios include Russian icebreakers sailing through the waters of the Arctic archipelago, Chinese bases built without the knowledge of Canadian authorities, and even an attack on the Canadian Arctic by the Russian military. The problem is that this bleak picture is based on highly theoretical scenarios and irrelevant observations. Worse still, it probably misses the real issues, which lie both in the need for the Canadian government to ensure a governmental presence in the North and to counter any challenges to its sovereignty in the Beaufort Sea and the Northwest Passage by the United States.

Are the Bear and the Dragon Real Predators?

On what basis can we claim that Russian icebreakers will ply the waters of the Northwest Passage, when they already have their hands full along the Siberian coast and are built specifically to support commercial traffic? On what basis can we claim that China could build a base in the archipelago without the work being detected? How can we claim that Chinese commercial vessels will sail through Canadian Arctic waters without asking for permission? What are these mysterious precedents of Chinese research vessels that, according to the authors, regularly dock on Canadian Arctic territory to illegally install telecommunications equipment?

The only known case of a Chinese vessel approaching the Canadian Arctic coast without a planned visit is that of the icebreaker Xuelong in Tuktoyaktuk in 1999, but this request was lost in the maze of Canadian bureaucracy. There was, of course, the case of the Chinese surveillance buoys, which were found (and removed) by the Canadian Armed Forces a few years ago: however, the qualitative leap between the presence of buoys and the establishment of structures on land would be very significant. Furthermore, the fact that the Canadian military recovered the surveillance buoys is more evidence that Canada is monitoring its Arctic and can respond to intrusions than the opposite.

Beyond these elements, which are more speculation than fact, proponents of the Sino-Russian scenario use generalisations to portray collusion between China and Russia, whose intentions would, of course, necessarily be hostile to Canada. Russia is aggressive in NATO countries’ airspace – that is true, but in the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea, in the context of the war in Ukraine – and therefore poses a threat in the Arctic. However, the frequency of Russian air patrols in North American airspace remains low (1, 2, 3). Russia has not withdrawn from the Arctic Council; Russia has never contested Canada’s or Denmark’s claims to extended continental shelves in the Arctic Ocean, even though these claims encroach on its own, and even when Canada extended its claimed territory in 2022. It is as if, under a tacit agreement that continues despite tensions in Ukraine, the Arctic coastal states refrain from contesting their neighbours’ claims [1]. Furthermore, cooperation between Russia and the other Arctic states continued after February 2022 at the Conference of the Parties to the international agreement for the prevention of unregulated fishing activities in the high seas of the central Arctic Ocean.

In the South China Sea, China has exerted strong military pressure to seize islands and sideline other regional players – that is correct – and therefore poses a threat in the Arctic. But what is the link between the Arctic and the China Sea? In the Arctic context, China has ratified the moratorium on commercial fishing in the central Arctic Ocean, in addition to adopting the Polar Code standards. China is increasing its polar scientific missions – that is correct – and these missions are said to have a dual civilian and military purpose – that is possible. China has begun participating in joint patrols with Russia, both aerial patrols south of the Bering Strait and naval patrols along the Northern Sea Route. Some authors conclude that China poses a short-term threat to Canada’s Arctic sovereignty. These assertions are based on assumptions and geographical extrapolations without any real evidence of hostile intentions in the Arctic. Formulating a hypothesis is not the same as asserting the existence of threats.

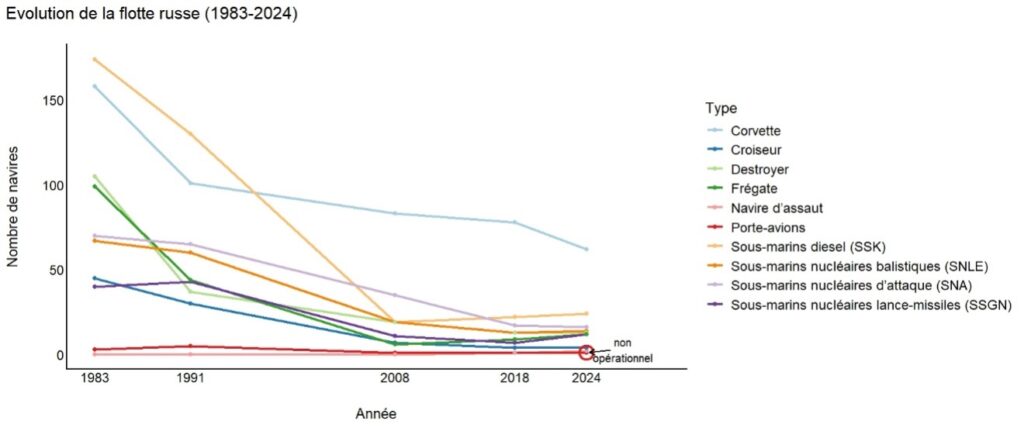

If Russia is reinvesting in its military sphere after years of rapid decline, it is notably with the aim of redeveloping its fleet and military assets, which declined significantly during the 1990s after the collapse of the USSR.

We can consider, for example, the evolution of Russian naval personnel since 1983 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Change in the number of vessels in the Russian fleet, 1983-2024

Figure 1: Change in the number of vessels in the Russian fleet, 1983-2024

It is clear that Russia’s fleet is nowhere near the size it was during the Soviet era, and has continued to decline except for submarines and frigates. There have been recent modernisations, but they have been slow (13 years of construction for the latest Neustrashimny frigate; 9 years for the latest Borei-class SSBN) due to underinvestment in shipyards and a loss of expertise following the departure of many engineers. The actual modernisations and recent launches do not compensate for the withdrawals. Efforts have been made on submarines, destroyers and frigates, reflecting a defensive posture (1, 2) known as the defence of the Barents Sea stronghold. The basis of Russian doctrine remains nuclear deterrence, while the naval forces increasingly have coastal defence units (frigates, corvettes) designed to protect Siberian economic assets and, above all, the launch area for ballistic submarines. These naval units are not well suited to long-range assaults. Furthermore, Russia has only two assault ships (and several smaller landing craft). None of the ships in the Russian fleet are ice-class.

Similarly, Western media widely reported on Russia’s strong communication during the deployment of Bastion mobile anti-ship missiles in 2018. However, these are essentially medium-range (300 km) coastal defence systems. They therefore do not pose a direct threat to Canada.

Finally, no new Russian military bases have been opened in the Arctic, except for a building housing a 250-strong battalion near the Nagurskoye air base in the Franz Josef Land archipelago. These reopenings of old bases (1, 2), which have been modernised, do not necessarily constitute a step towards an attack on Canada. Russia emphasises that it has strengthened its air defences and coastal radars, but once again, this reflects a defensive posture: Russia maintains the perception that it could be attacked by NATO forces, even though the exploitation of Arctic resources now accounts for around 10-15% of its GDP.

If any theatre of operations could give rise to concern about Russia’s military reinvestment efforts, it would be Norway, close to the Baltic Sea, where tensions between Russia and the West are felt. But precisely because of the outbreak of war in Ukraine, Russian naval manoeuvres in the Norwegian Sea have decreased, while the number of air patrols has remained relatively stable. In the North American Arctic, NORAD reported eight Russian patrols in the Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ) of Alaska or Canada in 2023, 12 in 2024 and eight as of 28 October 2025. This is close to the average since 2007 (around 12 patrols per year), which is fairly low, with relatively non-aggressive flight patterns: military flights in ADIZs are not illegal under international law, and NORAD considers that these patrols do not pose any danger. There is therefore clearly no aggressive military posture on the part of Russia towards other regions of the Arctic, but rather a genuine effort to modernise and increase its defence capabilities.

It is clear that Canada must not allow its weak capabilities for control, observation and surveillance of its Arctic domain to become entrenched over time. Similarly, especially in a context of political tension with Russia and China, it is important to maintain real vigilance, develop contingency plans in the Arctic and preserve real operational capability. The increase in maritime traffic due to climate change requires improved control and response capabilities, not only to counter military threats, but above all to be able to prevent the risk of accidents and environmental disasters. The long delay (five weeks) in rescuing the container ship Thamesborg, which ran aground in the Northwest Passage on 6 September 2025 and received little media coverage in Canada, should be instructive in this regard. However, these shortcomings do not mean that Russia and China are seeking to take over the Canadian Arctic. Furthermore, maritime transit traffic remains very low, and the recent media buzz surrounding the transit of a container ship between China and the United Kingdom via the Northern Sea Route cannot hide the lack of interest of most shipping companies in this activity (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6): in 2024, 97 ships transited via the NSR and 31 via the Northwest Passage (including only 10 commercial vessels), compared to more than 11,000 via Panama and more than 18,000 via Suez.

Meanwhile, in Washington…

While some believe the threat lies with Moscow and Beijing, others are looking south instead. This is the case for Adam Lajeunesse, director of the Canadian Maritime Security Network, Stéphane Roussel and, more recently, Franklin Griffiths, professor emeritus at the University of Toronto, who express serious concerns that the United States will undermine the sovereignty and security of the Canadian Arctic.

In addition to the tariffs imposed on many of its exports, Canadian society has taken note of President Trump’s threats of annexation (sometimes disguised as urgent invitations) and his questioning of border demarcations. What is more, the White House tenant has also threatened to annex Greenland and the Panama Canal, even if it means using force to achieve this.

It is impossible to gauge the seriousness of such threats, but the hostility, or at the very least the lack of consideration shown by the Trump administration towards Canada, may justify the formulation of more dangerous, immediate and pressing scenarios. One such scenario concerns the Canadian Arctic.

There are two maritime disputes between Canada and the United States in this region: one concerns the maritime boundary (territorial sea and EEZ) between the two countries in the Beaufort Sea, the other the legal status of the Northwest Passage, considered as internal waters by Canada and as an international strait by the United States.

In the latter case, fears sparked by the voyages of the SS Manhattan in 1969 and the USGC Polar Sea in 1985 were allayed following the signing of the Arctic Cooperation Agreement between the two countries in 1988, although the subject periodically resurfaces in debates on security in the Canadian Arctic. It was the first Trump administration that reawakened this old demon in 2019 when it ordered a freedom of navigation operation in the Canadian North, an operation that did not take place. This type of initiative involves sending ships into international waters that a state claims as its own in order to reaffirm the right of third parties to navigate freely in those waters. This is the scenario that Franklin Griffiths imagines in the near future, which would render the 1988 Agreement null and void.

There are several reasons why the American President might take such action: to intimidate Canada into making trade, economic (such as access to certain resources) or even territorial concessions; to destabilise a government with which he is negotiating; and even, why not, to give weight to his plan to absorb Canada.

Paradoxically, scenarios based on a Chinese or Russian threat could serve American aims, as they could provide the Trump administration with a pretext for action. The United States could thus justify an initiative against Canadian sovereignty by claiming to want to protect it from a takeover by Moscow or Beijing. Moreover, such action would send a signal to other powers that Washington has revived the Monroe Doctrine and that Canada, like the rest of the Americas, is once again the preserve of the United States. It is against such ‘help’ that Canadians must guard themselves, explain Lagassé and Massie (2025). The principle that Canada must guard against potentially overly intrusive assistance from the United States was first formulated in the 1970s by researcher Nils Ørvik (1973), but this is probably the first time it has been so relevant.

Nevertheless, Canada has more cards in its hand than one might think. The United States is singularly poor in terms of its ability to navigate the Arctic, with only three operational icebreakers (Polar Star, Healy and Storis). The recent agreement with Finland for the delivery of four icebreakers does not provide for the delivery of the first vessel until 2028. Sending a military unit that is not designed to deal with ice would be extremely risky, to the point where American ships might need Canadian assistance – which would greatly weaken the scope of the operation.

Another threat looms over the Canadian Arctic. A glance at a map of North America reveals how significant the consequences would be for Canada if the United States were to annex Greenland. Canada would find itself almost surrounded by American territory, with the United States having direct access to the Northwest Passage. Despite maintaining ocean access on the east and west coasts, Canada’s geopolitical situation would become very uncomfortable.

The risk of Washington launching a freedom of navigation operation will remain for the foreseeable future. The Canadian government must therefore be prepared to respond quickly to a potential crisis by symbolically deploying one or more Navy and Coast Guard units in response to the American initiative. In the medium and long term, this posture requires significant investment in equipment, infrastructure and operations. The windfall generated by the spectacular growth in the defence budget announced by the Carney government provides an opportunity to proceed with this reinforcement.

In addition to the need to counter a possible American initiative, there is another reason to support the growth of resources allocated to the Canadian Forces to operate in the Arctic, namely the growing importance of the Canadian Forces’ role as a constabulary and in supporting the operations of other departments in the region. The Department of National Defence is the only government organisation with the physical means to operate in the region and therefore to represent authority there. In this regard, it must ensure compliance with laws and the provision of services to local communities, as well as have the capacity to respond to emergencies. Climate change and the resulting increase in human activity in the region (resource exploitation, shipping, tourism) only serve to increase the demand for government services. Furthermore, the fulfilment of this mission complements and reinforces the mission to assert Canadian sovereignty in the region, as both require an effective and visible official presence.

It can be argued that defence efforts in the Canadian Arctic are aimed at countering Russian or Chinese threats, and that these efforts are insufficient. Waving the flag of loss of sovereignty and territory may be a good slogan, but this fear is rarely the basis for a coherent and rigorous Arctic policy. In reality, by protecting its territory, Canada is primarily defending itself against American ‘help’.

[1] The only exception was when Washington published its claim in 2023, which Moscow contested, not so much because of the maritime space claimed by the United States, but because, for Moscow – and this point is credible – Washington cannot invoke Article 76 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea if the US has not ratified the convention.

Comments are closed.