The last two decades have been difficult for Canadian foreign policy. Successive governments in Ottawa have been struggling to articulate a coherent policy anchored in our values and interests as well as allocating resources toward these objectives. In short, we have lost control of our own destiny in the world.

In such confusing times, a first step toward rethinking our place in the world should start with understanding Canadians’ foreign policy preferences and ambitions. To that end, the Canadian Defence and Security Network convened some of Canada’s leading experts to design a comprehensive public survey. A University of Calgary-led group worked with Nanos Research to deploy a survey in August 2020, asking 1,504 Canadians about their attitudes toward foreign and defence policy.

Click here to view the survey results.

We first asked Canadians what they felt should be our role in the world. By far the most common response (31% of respondents) was that Canada should be a peacekeeper, a mediator, or a voice of reason in international affairs. Other common responses spoke about Canada being a leader/decision-maker, being a role model and advocate for human rights, and helping those in need.

These responses show that Canadians generally believe that our contribution to world affairs should focus on deescalating tensions in a fraught international environment where reasonableness is in short supply. To be clear, this is an ambitious role for any country, let alone a small power like Canada who has neither the economic nor military might to steer the course of world events. Furthermore, our traditional means of influence, leveraging international organizations, has been limited by the increasing entanglement in great power competition. What we can do, however, is direct our energy and determination toward building stronger relations with like-minded countries – such as the UK, France, Germany, Japan, Australia, and South Korea – and mobilize these networks to carve out zones of order in a turbulent world.

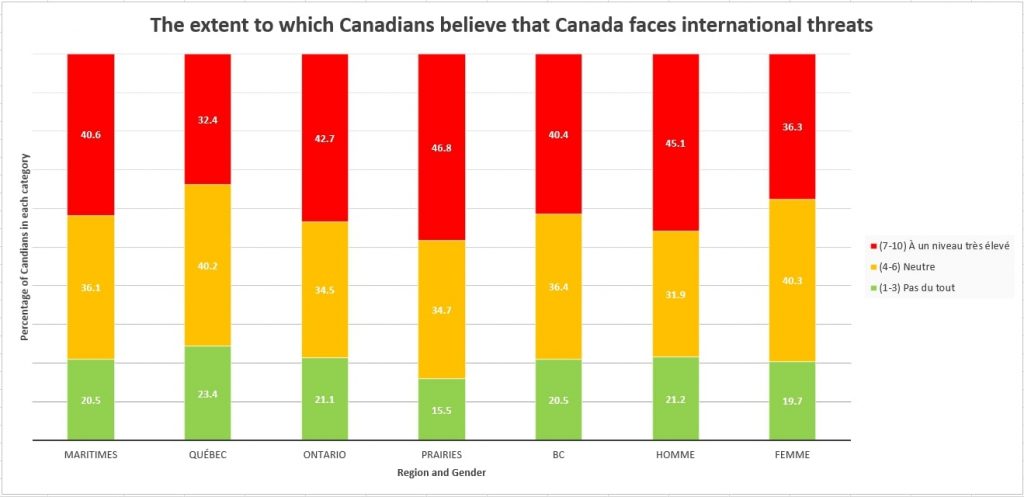

Second, we asked to what extent, if any, they thought Canada faced international threats. 41% of respondents answered that such threats were important, while 36% were neutral, and 20% to a low extent. This indicates Canadians’ awareness of the deteriorating security environment in the world. When prompted on what they believed was the most and second most important threats, China (34%) was identified as the main menace, with the US/Trump very close (31%), followed by cyber-attacks (16%), and terrorism (13%). Canadians’ patience with China and the US is eroding and, consequently, this is increasing the domestic cost of the government’s efforts to promote better relations with these countries.

Figure 1: Perceptions of the threat among Canadians (disparities between region and gender)

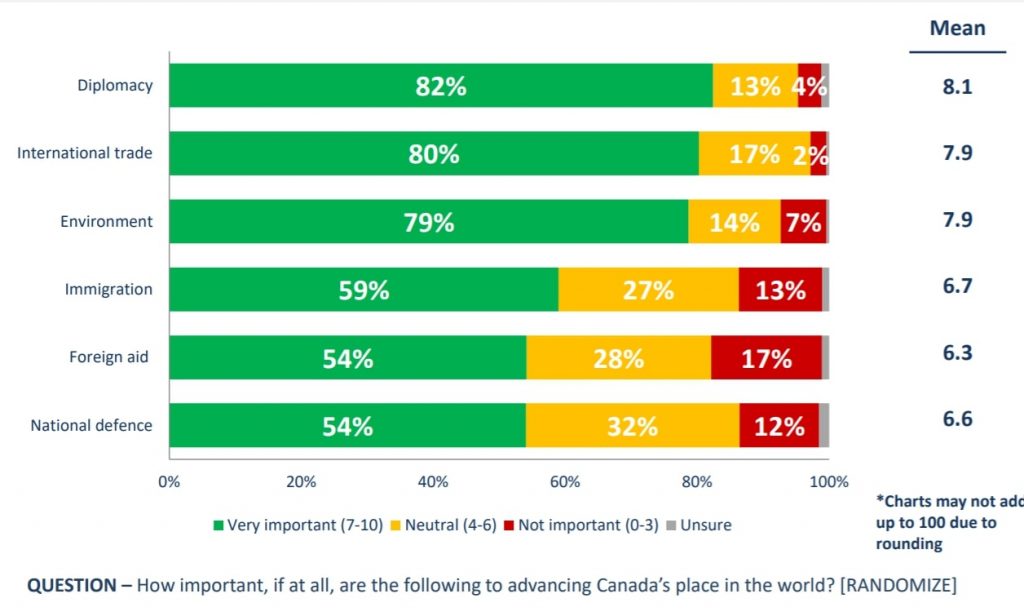

Third, we examined how Canada should promote its place in the global environment. The most common responses were diplomacy (82%), international trade (80%), and environmental policy (79%). Comparatively, immigration (59%), foreign aid (54%), and national defence (54%) were considered less important as foreign policy tools. This focus on diplomacy, trade, and environmental policy aligns with the notion that our added value in world affairs is our capacity to transcend narrow self-interests and work toward broader long-termed goals. What is surprising, however, is that we haven’t really invested in these tools. The current budget of Global Affairs Canada for diplomacy, advocacy, and international agreements is relatively modest (sitting close to $900 million) compared to the resources invested in either foreign aid (close to $5 billion) or national defence (around $21 billion). Although money allocation is an imperfect indicator of a government’s priorities, there seems to be some support amongst Canadians to increase resources devoted to Canadian diplomacy.

Figure 2: Importance of foreign policy tools to promote Canada’s place in the world

Fourth, on the question of the balance between promoting our interests and our values, 59% of Canadians argued that we should prioritize promoting our values around the world while only 17% suggested we should focus on our interests, with some important variance found between regions and gender. A very large number of Canadians (36%) identified trade and economic exchange as our primary national interests, while 16% answered environmental responsibility, 8% security, and 6% oil and gas/energy.

When probed specifically on what values should be promoted, 25% answered inclusivity, fairness, and equality; while peace (13%), human rights (13%), and democracy (11%) followed. This emphasis on inclusivity is very interesting. In terms of foreign policy, Canadians articulate the need to be authentic – to use Charles Taylor’s notion – on the world stage. This could be achieved by anchoring our policy in our shared sense of self as a pluralist society, striving to develop a political project that recognizes the strength of diversity. In this, the Trudeau government’s focus on a feminist foreign policy is a good first step as it recognizes our attachment to gender equality. Nevertheless, it does not fully leverage the breadth of a society that negotiates, imperfectly, bilingualism, the inclusion and recognition of black, indigenous, and persons of colours, and a commitment to promote LGBTQ+ rights. Clearly, there is room for the Government of Canada to redefine its priorities and be more audacious.

This is just a glimpse of what we are learning on Canadians’ attitude toward foreign policy, but two major conclusions seem to derive from these results. Firstly, Canadians want to be involved in world affairs, engaging vigorously in diplomacy to promote our values – especially our dedication to a political project centered around tolerance and diversity – and our economic interests. Secondly, aggressive posturing from Beijing and Washington, D.C. are perceived as the main threats to Canadian sovereignty and international stability. Canadians have taken note of the mounting competition between these two powers and are increasingly distrustful of them. This warrants efforts by the Canadian government to develop better relations with other states around the globe and invest resources in our diplomatic corps in order to reduce our dependency on China and the United States.

Comments are closed.