|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Is war over Taiwan coming? Yes, possibly within five years. Recent statements by U.S. President Biden have reinforced an implicit U.S. security guarantee for the self-governing island democracy, such that there is little doubt that the USA will seek to defend Taiwan against a Chinese attack. The American commitment is real, but the USA cannot defend Taiwan alone. For that, it needs its allies to help defend, and no ally is more important for that than Japan. This paper will examine Japanese-Taiwanese relations and argue that Japan is in fact moving toward an implicit obligation to assist in the defense of Taiwan against a Chinese attack, despite several factors that might complicate that assurance. The paper will examine the rise of China and its determination to force a unification with Taiwan, by coercion or force if necessary. Then it will examine the evolution of Japanese diplomatic and defense policy toward Taiwan in recent years. But cautions are necessary; there are several factors that might cause Japan to waver in its implicit obligation or to be less effective than it could be.

China’s Ambition

Taiwan remains the elusive piece of China’s reunification. The strategy of enticing Taiwan into China’s orbit peaked in the 1990s when China was on its best behavior and sought to use the “One Country, Two Systems” policy as a way of bringing Taiwan into some sort of loose (but legal) association. Hong Kong was supposed to be the demonstration test case of this after July 1, 1997. Twenty years later, the mainland crackdown on civil liberties and democracy in Hong Kong makes it clear that China is systemically incapable of tolerating political pluralism and democracy. U.S. assessments of Chinese military capabilities last year projected a six-year horizon within which China will be ready to take military action. Xi Jinping in particular has taken on reunification as his grand achievement in his likely third term as head of the Communist Party. Xi needs a great achievement to justify his continuing leadership, if only to rank himself with Mao Zedong in Chinese history. But time is working against Xi in two respects: Taiwan’s public feels less and less Chinese. Second, China’s slowing economic and demographic growth, the unsustainable “zero Covid” policy, and the problems of debt, environmental damage, and corruption of the Belt and Road Initiative have begun to weigh on that grandiose vision as well. All of this amounts to a hard domestic political reality: Xi is running out of great things to achieve. But Taiwan would be that achievement; not even Mao obtained it. Assuming the 20th National Party Congress reappoints Xi as its top leader in fall 2022, a five-year clock on Taiwan would start ticking.

The Japan Self-Defense Force: The Military That Isn’t Allowed

Article 9 of the 1947 Japanese constitution – written by the American Occupation authorities – explicitly prohibits Japan from having a military. Three years later, the Americans regretted that clause and created the National Police Reserve and the National Safety Agency, the precursors to the Self Defense Forces (SDF) and the Ministry of Defense. During the Cold War, American protection helped Japan, but American pressure to increase its defense contributions were constant. Although the political opposition steadfastly opposed any change to Article 9 or any increase in SDF capabilities, the dominant Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) gradually enacted changes. One of the most important occurred in 2015 when Japan expanded its definition of self-defense to include other countries: “When an armed attack against Japan occurs or when an armed attack against a foreign country that is in a close relationship with Japan occurs and as a result threatens Japan’s survival and poses a clear danger […].”

Japan’s SDF has already been involved in a variety of overseas activities short of combat. It has made a number of contributions to UN PKOs. After the 9/11 attacks in the USA, Maritime SDF units operated in the Indian Ocean from 2001 to 2010, and anti-piracy patrols continue in the Indian Ocean. In 2004, the Koizumi government sent a battalion of non-combatant troops to Iraq at the American request, the “Japanese Iraq Reconstruction and Support Group,” which lasted five years.

In contrast to the stagnation in the late 1990s to the 2013 period, Japan has since increased its defense spending by over 18% in constant dollar terms and over 24% in yen terms. According to the Stockholm Institute of International Peace Research (SIPRI) it is $54.1 billion/year, comparable to Germany and France, and more than South Korea, Australia and Canada. It has a modern fleet of non-nuclear submarines, destroyers, excellent anti-submarine warfare capabilities, and a modern Air Self-Defense Force as well. Although there are several areas in which the SDF needs to improve, the naval assets in the region show that Japan has substantial forces to supplement the USA.

Source: IISS The Military Balance 2022.

Perhaps most important, Japan is in the key position to cooperate with the United States over Taiwan: it hosts U.S. forces in Okinawa, as well as its own, with critical air and sea ports near the potential scene of conflict.

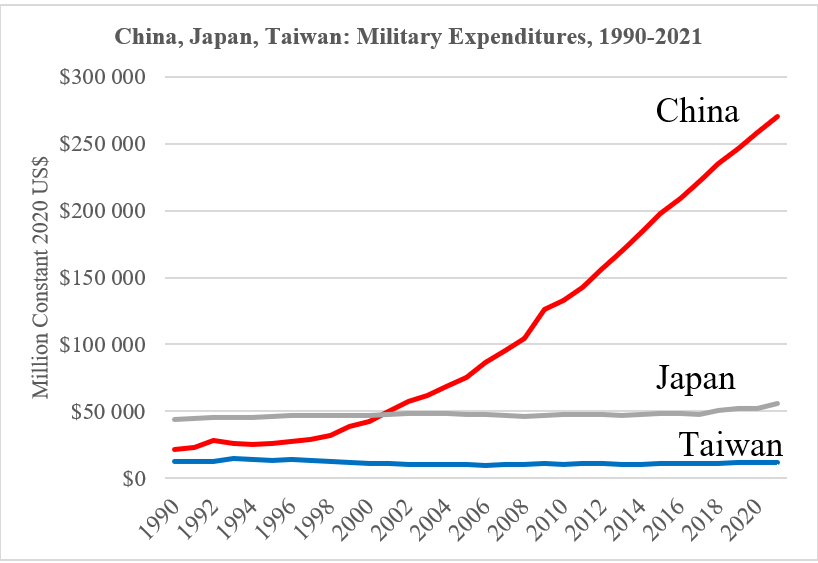

Compared to China’s military spending, however, neither Taiwan nor Japan comes close.

Source: SIPRI, 2022.

Japan’s Changing Relations with a Country That Doesn’t Exist

Japan severed its diplomatic ties with Taipei in September 1972 but maintained an unofficial office there which functioned as an embassy in all but name. Economic and social ties between Japan and Taiwan remained very good. Taiwanese polled report good feelings toward Japan, and the historical legacies that burden Japan’s relations with Korea, China and the Philippines are far less pronounced in Taiwan. Both Lee Teng-hui, Taiwan’s first directly elected president, and Tsai Ing-wen, its current president, have spoken favorably of Japan, and Tsai has a Japanese-language Twitter feed with 1.4 million followers.

Japan’s relations with China have long been torn between the more bellicose “hawks” and the conciliatory “doves” in the ruling LDP. Among the latter had been Fumio Kishida. After his election as Prime Minister in October 2021, however, most analysts see Kishida as turning into a hawk and the doves disappearing.

The LDP established a “Taiwan Policy Project Team” in early 2021 for talks between legislators (not government officials) in foreign policy and defense areas. Rumors of a “Japan Taiwan Relations Act” patterned after the 1979 American law authorizing defensive arms sales to Taiwan, however, seem unlikely. By 2021, concerns about the situation in the Taiwan Strait was becoming much more “mainstream” in Japanese politics: “[…] worsening frictions across the Taiwan Strait throughout 2021 did focus Japanese media, politicians, and policymakers on the risks and potential impact on Japan of a possible conflict – perhaps to an unprecedented degree.”

The shift toward a more forward thinking about Taiwan is at least partly attributed to the increased willingness of American and European states to engage with Taiwan. Japan also recognizes the common interests of the two countries: “[…] Japan now actively seeks to promote closer defense ties with liberal and democratic states in Asia as an act of strategy. Within this framework, Taiwan is a top candidate for closer relations as a fellow island democracy close with the United States and facing threats from China.”

Japan’s growing resolve over Taiwan was reinforced by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Japan reacted quickly and decisively against the Russian Federation, imposing sanctions along with the USA and European Union, freezing Russian assets held in Tokyo, cutting off SWIFT banking access, and freezing Russian officials’ assets as well. As Defense Minister Nobuo Kishi stated, “If the international community somehow allows or condones Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, it might send a wrong message that such actions can be tolerated in other parts of the world, including the Indo-Pacific. […] Ukraine may be East Asia tomorrow.”

Policy Recommendations

- It is crucial to maintain and increase NATO visits and exercises in the Indo-Pacific, and further institutionalize them; China needs to see a western alliance that can watch both European and Indo-Pacific theaters simultaneously. Canada as a NATO member and a Pacific power has a special responsibility in this respect. China’s recent harassment of RCAF aircraft is meant to intimidate Canada.

- S. allies need to think realistically about 5-year maximum time frame and take steps accordingly. Fortunately, Ukraine has created conditions for serious policy change in Japan.

- Western allies need to work through joint responses “just short of war” scenarios, such as a Chinese naval blockade of Taiwan masquerading as a “quarantine.”

- Explore strategy and arms purchase coordination with Taiwan and Japan. U.S. leaders are beginning to think seriously about a war on Taiwan, and it would be crucial to have a sense of that government’s strategy and include Japan and other allies in the consideration.

- Keep the “Country that Doesn’t Exist” and “Military that Isn’t Allowed” Policies. Pushing Japan to create its own Taiwan Relations Act or abolishing Article 9 carries political costs and diplomatic risks for little change in real policy.

Steven F. Jackson is professor of political science at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. After receiving his bachelor’s degree in International Relations at Stanford University in 1981, he taught English in Xi’an China from 1981 to 1983. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Michigan and joined the faculty at Indiana University of Pennsylvania in 1994. He is author of China’s Regional Relations in Comparative Perspective (Routledge 2018), as well as numerous chapters and articles on the international relations of East Asia.

Comments are closed.