|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The idea that Canadian territory could be attacked by a Russian air, ballistic or naval attack is not new. Scientific or media literature testifies to the recurrence of this concern among Canadian opinion, a fear fuelled by political friction with Russia. This tension has been particularly acute since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, and the resumption of air patrols by Russian bombers in the Arctic. Contrary to the behaviour of Russian forces in the Baltic or the Sea of Japan, an analysis had pointed out that the frequency of these patrols, sometimes conducted to the edge of U.S. or Canadian airspace in the Arctic, had nothing illegal in itself, presented a low risk and, above all, hardly reflected any major military pressure.

In general, scenarios of Russian aggression against Canada are difficult to conceive outside the framework of an escalation triggered by either side. To date, Russia has been careful to contain the conflict to Ukraine, while sending clear political and military signals (cruise missile attacks on Ukrainian sites near the Polish border) to NATO about where the red lines should not be crossed.

Ballistic Threat.

As in the Cold War era, the shortest route from Russian launch sites to Canada is through the heart of the Arctic. This led to the decision to build the Distant Early Warning (DEW) radar line built in the 1950s (1954-57) and upgraded to the North Warning System (NWS) in the late 1980s. The surveillance carried out by the NWS is completed by the Canadian base of Alert (electronic listening) and by the American base of Thule in the extreme north of Greenland. Yet, any ballistic attack leaves little time for reaction: it is more the detection by satellite imagery of the preparation for launching land-based missiles (opening of silos) that can give an indication of the imminence of an attack. Furthermore, an attack could also be launched from strategic submarines stationed, given the range of their missiles, in the Atlantic or Pacific. As such, it is rather on the political level that the detection of a possible attack must be carried out: is the Russian government’s discourse changing? Is there an inflection in the discourse on political thresholds? For the moment, if Russia has maintained an ambiguity on the transition between conventional and nuclear weapons, the Russian doctrine sticks to the idea that Moscow will use nuclear weapons in Ukraine only in case of an “existential threat” against Russia, as Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov declared on Tuesday, March 22. Knowing that the Ukrainian army does not have nuclear weapons since 1994 and no chemical weapons, what does an existential threat in Ukraine mean? Any credible political threat to the regime, from this point of view, could be interpreted by President Putin as an existential threat. In this light, displaying the fall of the Russian government as a political objective for the West could prove risky.

It can be observed that Russia seems to have perfectly mastered what is called the “grammar of deterrence,” while leaving ambiguity about the notion of “existential threat,” which corresponds to what the West calls “vital interests.” However, in this area, nuclear deterrence with mutual assured destruction (MAD) remains effective for the moment.

Naval Threat.

The latter is of the same order as the ballistic missile threat: submarines can fire missiles, nuclear or conventional (range of about 1,000 km for hypersonic Zircons), from many points along Canada’s maritime approaches. It is somewhat unrealistic to think that we can guard against such surprise attacks. As with possible air raids (see below), the possibility of an attack by conventional missiles fired from submarines raises the question of the usefulness of such an attack for Russia: after damaging a military base or a port, what advantage would Russia gain from knowing that it would have to deal with the retaliation? This type of threat would only make sense in the context of a conventional escalation, for example in response to NATO’s entry into the conflict through a no-fly zone.

Aerial Threat.

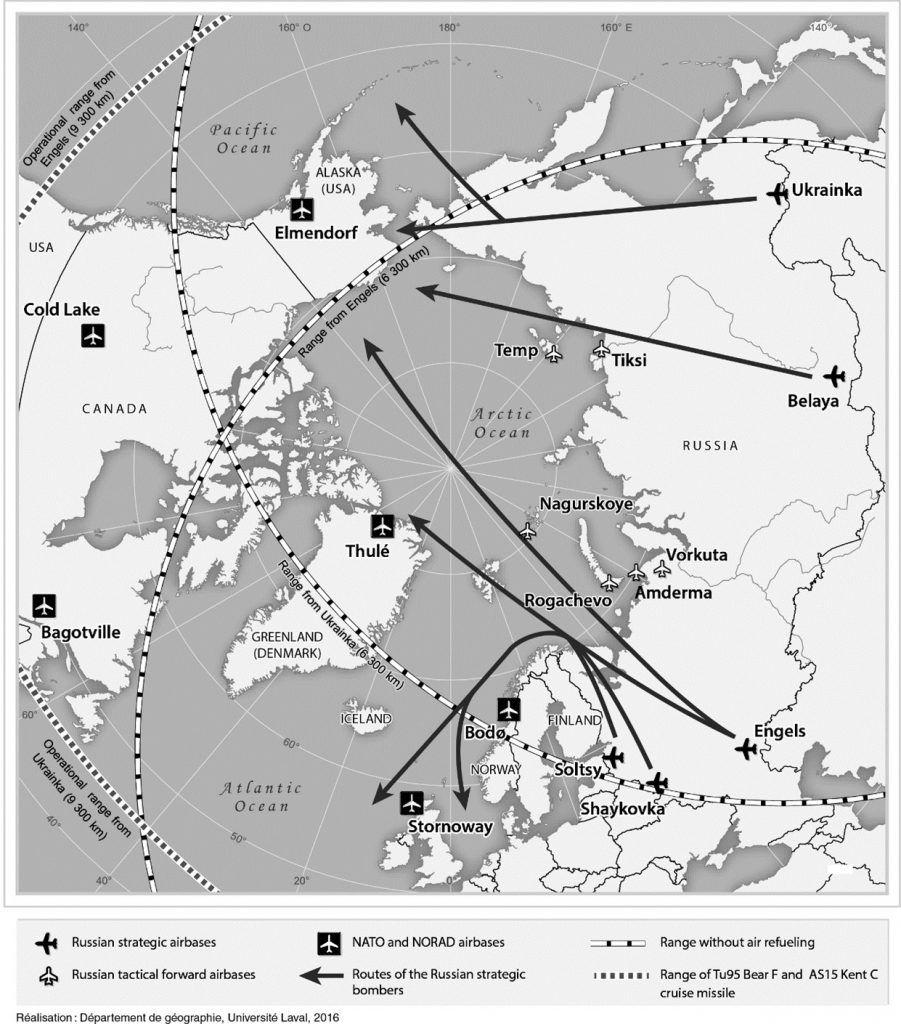

A Russian aerial attack against Canada would likely come through the Arctic. So, what assets do the Russian Air Force have? The heavy bombers (Tu-95 Bear, Tu-160 Blackjack) are based at airbases further south, Engels, Shaykovka, Belaya or Ukrainka, but it is easy to transfer them with their logistical support to Siberian airfields. This includes those that have been recently renovated (and not built ex-nihilo), such as Nagurskoye, Rogachevo, Sredny Ostrov, Temp (Kotelny) or Anadyr. The risk is that this redeployment might not be detected by satellite observation. Conversely, an escort of fighters for these bombers seems more difficult to deploy: Russian fighters such as the Sukhoi-35 Flanker E (1,800 km) or the modern Sukhoi-57 Felon (2,200 km) have insufficient range to be able to escort them to Canadian territory, unless they resort to in-flight refuelling with pre-positioned Ilyushin Il-78s, of which the Russians have only a small number. However, this would also increase the risk of advanced detection by the Thule or NWS radars because of the pre-positioning of the refuelling planes, and because the refuelling operation is carried out at medium altitude.

Figure 1. Location of Russian strategic air force bases and bomber patrol routes. Source : Lasserre et Têtu, 2016.

These bombers have long ranges (Tu-160: 6,100 km; Tu-95: 7,500 km), which enables them to reach the northern part of the Prairie provinces from Siberian airfields. Equipped with conventionally armed cruise missiles, such as the AS-15 Kent (2,500 km) or hypersonic semi-ballistic missiles fired from aircraft such as the Kinjal (2,000 km), the bombers could then threaten major urban centers. Assuming, of course, that they had not been intercepted beforehand after such a long incursion into Canadian territory. The attack could also target NWS radar stations or air bases such as Cold Lake in northern Alberta, or Elmendorff in Alaska, which would allow bombers to launch their missiles shortly before their arrival over Canadian territory in the case of an attack on Cold Lake. The stand-off capability of cruise missiles makes the vulnerability of installations in the Far North very tangible, with a reduced time between detection and interception. Everything would then depend on the number of missiles fired, which could saturate the available anti-aircraft equipment, Patriot batteries or Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) to counter semi-ballistic hypersonic missiles like the Kinjal. Such a threat seems difficult to counter completely, especially in a first strike, as it requires airborne warning and control system (AWACS) radar aircraft and interceptors (CF18, F22, F15) to conduct combat air patrols very far from the bases.[1] It would thus be challenging, although not impossible, to offset such an attack.

The farther south one goes, the more Russian aircrafts would be forced to enter deep into North American airspace to get within range, making them easier to intercept.

Therefore, two questions remain:

- What is the effective range of NWS radars, possibly supported by flights of advanced warning aircraft (AWACS, e.g. E-3 Sentry), in case of fear of possible Russian incursions? In the media, there are statements by experts that the North Warning System is “incapable of responding to modern missile technology.” North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) officers, who oversee the control of approaches to North American airspace, have surely analyzed the detection performance of NWS radars since 2007, depending on whether Russian patrols were flying at high or low altitudes. From this examination, knowing that radars must also be effective against missiles, and that hypersonic missiles are difficult to intercept without a high density of anti-aircraft assets, will come the recommendation to modernize, or not, the NWS’ detection systems.

- What could be the doctrine of use of such Russian attacks? After all, what would be the point of Russia destroying the Cold Lake base with a single raid if its objective is not a full-scale war against NATO? What would be the point of such an isolated incursion, if not to trigger a retaliatory raid and then war against the West? From a strict point of view of political or military effectiveness, such an isolated raid is therefore unlikely, that is as long as we place ourselves in the framework of a reasoning based on a shared rationality of military cost/political benefit. Answering the question of Canadian military preparedness also raises the question of intelligence on Russian government representations and posturing: are we still in the realm of the rational, or do decisions become unpredictable?

We Cannot Disconnect the Political From the Military.

These questions underscore that military capability issues do not adequately sum up the Canadian security equation. It is much more the question of objectives, the political context of the evolution of the conflict, that must provide the basic analytical framework: why would Russia attack Canada or a NATO country?

The evolution of the conflict guides the parameters of the Russian government’s reasoning. In the context of the fog of war, one is obviously reduced to conjecture, but some elements are worth emphasizing. There seems to be no reason for Russia to strike a Canadian base unless there is a major shift in the conflict. This inflection could come from NATO, which would have intervened, through a flight ban over Ukraine for example, or because, having lost the war and seeing its army experiencing great difficulties and conscripts surrendering en masse, Vladimir Putin believes that a deliberate escalation in terror would be the best option. Black scenario, hypothetical, but not unthinkable: the Russian army has recorded, out of 200,000 soldiers engaged, losses ranging from 7,500 to 15,000 killed according to sources (the Russian army reported only 498 dead as of March 16), including 9,861 dead according to a Russian daily newspaper, and from 14,000 to 21,000 wounded, i.e., about 5% killed and losses of between 10 and 15%, which is a very high attrition rate in a month of fighting. For the record, bearing in mind that these two conflicts are not of the same nature, the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan cost the Red Army some 14,500 deaths between 1979 and 1989. Localized counterattacks underline the fact that the Ukrainian army has not lost its capacity to react. The continuation of the conflict points to the cohesiveness of the Ukrainian army; to the management of ammunition, with the Russian stockpile of cruise missiles diminishing, while it appears that Western arms deliveries to Ukraine are ongoing. Will the cohesion of the Russian army be maintained? Would the tactical and logistical difficulties incite the government in a headlong rush, with massive bombings, the use of chemical weapons, or even, in case of a Russian perception of great fragility, recourse to nuclear weapons?

Additionally, Vladimir Putin’s regime seems to rely increasingly on a militaristic ideology whose ultimate goal is “the victory of the Russian world” over “hostile Western forces that threaten its survival” and where war is seen as not only an acceptable, but the most effective tool for achieving geopolitical goals. This discourse underscores that the question of the weight of Russian leaders’ representations and policy objectives remains crucial. It may evolve as the war in Ukraine stalls, and even turn to Russia’s possible tactical disadvantage. While it is hard to imagine a first use of force by Russia against NATO, the risks of accidental escalation or headlong rush are never zero.

[1] This, incidentally, underlines the relevance of long-range fighters to protect large Arctic areas. This is not a characteristic of the F-35, whose range is very short, 1,100 km compared to 1,300 km for the F-22, and 1,800 km for the F-18.

Comments are closed.