|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

On February 23, 2025, German citizens will be called to the polls for early federal elections, a rather rare event in the country’s political history, marking only the fourth early dissolution of the Bundestag since the Second World War. Originally scheduled for September 2025, these elections are the result of the collapse of the coalition government led by Chancellor Olaf Scholz.

Since taking office in 2021, Scholz has governed almost entirely against a backdrop of international crisis, marked by the war in Ukraine. The Russian invasion of February 2022 triggered a Zeitenwende, a strategic turning point that forced Berlin to review its defence and security posture. Under pressure from within and from his allies, Scholz announced a special €100 billion fund to modernize the Bundeswehr and boost military support to Kyiv.

The Zeitenwende led to an increase in the defense budget and the launch of new equipment orders. However, its impact remains limited due to cumbersome bureaucracy, an armaments industry ill-adapted to current needs, and the absence of an effective rearmament of the Bundeswehr. At the same time, while Germany has stepped up its support for Ukraine and accelerated its energy diversification, it is still struggling to make good the shortcomings in its army’s capabilities and to define a coherent strategy in the face of Russian and Chinese threats.

On the political front, the Chancellery’s handling of the conflict has drawn criticism from both its coalition and opposition parties, notably the conservative CDU/CSU and the Greens, who are calling for a more robust approach. Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, a member of the Greens, called the conflict “the end of German restraint in foreign and security policy”, while Christian Lindner, a member of the FDP, spoke of a “rude awakening”.

The break-up of the “Tricolor Fire” coalition in November 2024 was part of a double crisis, both internal and geopolitical. Having come out on top in the 2021 elections with 25.74% of the vote, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) failed to win an absolute majority – a common occurrence in German federal elections – and was forced to form an alliance with the Greens (14.75%) and the Liberal Democratic Party (FDP, 11.45%). But this fragile alliance could not withstand the growing tensions, exacerbated by disagreements over economic policy, the energy transition and Germany’s military commitment.

The situation reached a breaking point in November 2024 when Scholz sacked Finance Minister and FDP leader Christian Lindner, leading to the implosion of the coalition. Deprived of a majority, Scholz submitted a motion of confidence on December 11, 2024, which was rejected five days later. President Frank-Walter Steinmeier dissolved the Bundestag on December 27, 2024, calling early elections for February 23, 2025.

These elections are of strategic importance for Germany, Europe and their allies. This article examines Germany’s military support for Ukraine in this electoral context. It begins by demonstrating the scale of the Zeitenwende and the challenges it raises, then traces the evolution of German commitment to Ukraine since 2014, with particular attention to the acceleration of support after 2022. It then examines the positions of the main parties on these issues and their vision of Germany’s role in the conflict. Finally, it considers the post-election outlook, assessing coalition scenarios and potential strategic adjustments, particularly in relation to transatlantic relations and Donald Trump’s return to the White House.

Germany and the Zeitenwende

The large-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 came as a major shock to Germany. After seven decades of restraint in defence policy, the outbreak of a conventional war in Europe had a profound impact on the political elites in Berlin and on public opinion.

We need to understand the context in which German defence policy developed in the post-World War II period. The Federal Republic of Germany’s (FRG) accession to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1955, made possible by the 1954 Paris agreements, was accompanied by strict limitations on the use of force, prohibiting all external military intervention. Subsequently, German reunification, formalized in 1991 following the 1990 Moscow Treaty, led to a significant reduction in the number of military personnel. The armed forces underwent major transformations over the following decades. The abolition of conscription in 2011, followed by structural reform between 2011 and 2012, led to a reduction in the number of soldiers and military bases.

February 2022 represents a real break in the way German government and society understand their strategic environment. For Olaf Scholz, “This is a historic turning point. It means that the world after will not be the same as the world before”. An analysis shared by FDP leader and Finance Minister Christian Lindner, who points out that “The war in Ukraine is waking us all up from a complacent dream”. This shift is perhaps most marked among the Greens, as illustrated by Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock’s statement: “Today may mark the end of Germany’s particular restraint in foreign and security policy”.

This shift has also taken place within German society. Recent opinion polls reveal that the majority of Germans now perceive Russia as a threat to their security. A significant proportion of the population considers that the Russian government represents a risk to national interests. Thus, 66% of respondents believe that Russia poses a threat to Germany’s economic stability and security, while 54% consider support for Ukraine to be in Germany’s national interest.

Despite these concerns about Russian aggression, the German population remains divided on the question of stepping up military support for Ukraine. Only 44% are in favour, while 47% are against. Similarly, support for sending Taurus missiles is limited, with only 36% in favour. However, 45% of respondents believe that Ukraine should be allowed to use Western weapons to strike targets in Russia, which is one of the main points of debate concerning Taurus missile deliveries.

Since the start of the conflict, support for Ukraine has been gradually eroding. A segmented analysis of opinion trends shows that the group most in favour of aid has been declining since October 2023, while segments more skeptical of such assistance have seen a slight increase. This evolution shows that the consensus in favour of greater military, economic and humanitarian commitment to Ukraine is running out of steam.

This is in line with the SPD’s reluctance to escalate the conflict and the risk of German involvement in the war, as well as more isolationist or pro-Russian tendencies on the far right (AfD) and anti-militarist tendencies on the left (Die Linke and BSW).

German involvement in the war in Ukraine

Following the illegal annexation of Crimea and military actions in the Donbass in 2014, Germany emerged as a major diplomatic player in the management of the Ukrainian crisis. Under the leadership of conservative Chancellor Angela Merkel, Berlin helped set up the Normandy format, bringing together Ukraine, Germany, France and Russia, and played a central role in the conclusion of the Minsk II agreements. At the same time, Germany helped shape European sanctions against Moscow, while strongly condemning Russia’s actions.

However, this diplomatic involvement contrasted with structural limits in terms of defence. Because of its energy dependence on Russia, Berlin refrained from canceling the Nord Stream project, revealing an ambivalent approach to Moscow. In addition, the Bundeswehr was facing major capability deficiencies, compromising its ability to respond to European strategic challenges.

A report by the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Armed Forces, published in 2018, pointed out that only a minority of military equipment was then in working order: 27% to 30% of fighter aircraft, 20% of transport aircraft, 22% of transport helicopters, 19% of attack helicopters, 47% of tanks, 38% of frigates and no submarines. A Ministry of Defense report published at the same time also highlighted the lack of clothing and tents, compromising the participation of German soldiers in NATO missions.

Thus, despite its leading diplomatic role in managing the Ukrainian crisis from 2014 to early 2022, Germany presented a reduced military capability, illustrating a persistent gap between its international commitment and its strategic readiness.

When the coalition government was formed on December 8, 2021, Germany reaffirmed its commitment to a balanced approach between dialogue and firmness towards Moscow. The government’s program emphasized the need for stable bilateral relations, while strongly condemning the annexation of Crimea, the violence in eastern Ukraine and Russia’s destabilizing actions. It also stipulated that any lifting of sanctions remained conditional on full implementation of the Minsk agreements.

The coalition agreement did not qualify Russia as a threat to Germany’s security. Indeed, despite these tensions, Berlin maintained a willingness to cooperate with Moscow on future issues, notably in the fields of hydrogen, health and climate. At the same time, Germany denounced the restrictions imposed on civil liberties in Russia and showed its support for Russian civil society, notably by facilitating the mobility of young Russians to its territory. With regard to arms exports, the German government intended to strengthen control mechanisms at both national and European level.

Faced with rising tensions in late autumn 2021, however, Chancellor Olaf Scholz was soon criticized for his overly cautious and ambiguous approach, in particular his reluctance to suspend certification of the Nord Stream 2 project. This pipeline crystallized the debate on Germany’s stance towards Moscow.

On February 22, 2022, as Russia unilaterally recognized the independence of two separatist regions in eastern Ukraine, Scholz finally announced the suspension of the Nord Stream 2 project. This decision marked a turning point in Germany’s policy towards Russia, and a hardening of its stance against Moscow’s actions. This change is part of the strategic break announced by Scholz on February 27, 2022 in his Zeitenwende speech, which defined a major repositioning of Germany’s defence policy and its involvement in the Russian-Ukrainian conflict.

Addressing the Bundestag, Scholz outlined the main thrusts of this reorientation. First and foremost, Germany is committed to actively supporting the Ukraine with military aid, including the supply of weapons, justifying this commitment by the need to defend the principles of freedom and democracy in the face of Russian aggression. At the same time, Berlin, in coordination with the European Union, adopted an unprecedented sanctions regime targeting Russian financial institutions, state-owned enterprises, strategic technology exports, and economic and political elites close to the Kremlin.

On the security front, Germany has announced a stronger commitment to NATO, reaffirming its determination to defend every inch of allied territory. This is reflected in the increased deployment of troops in Lithuania, Romania and Slovakia, as well as in the increased security of maritime areas in the North Sea and the Baltic Sea. On a more structural level, Berlin has undertaken a substantial modernization of its national defense. A special €100 billion fund has been allocated to the Bundeswehr to improve its operational capabilities, particularly in terms of equipment, air defence and cybersecurity. Germany is also committed to raising its defence budget to 2% of GDP, in line with NATO targets, and to strengthening European cooperation in military innovation.

In the energy field, Berlin is initiating a strategic reorientation aimed at gradually reducing its dependence on Russian hydrocarbons. This transition is based on the accelerated development of renewable energies, the construction of liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals to diversify supply sources, and the implementation of an economic aid plan designed to mitigate the impact of the energy crisis on households and businesses.

However, this transformation is not without its tensions and challenges. The Zeitenwende, presented as a major turning point in Germany’s defence and security policy, is struggling to materialize in any significant way. In particular, Germany has been slow to authorize the transfer of Leopard 2 tanks to the Ukraine, citing legal, strategic and diplomatic considerations. Under German law, any country acquiring these tanks must obtain Berlin’s approval before re-exporting them. Under pressure from Poland and Finland, the German government is hesitating, fearing an escalation of the conflict. Berlin also wanted the USA to commit to supplying M1 Abrams tanks before sending the Leopard 2s, to ensure a concerted approach. On January 25, 2023, in the face of mounting pressure, Germany finally approved delivery of the tanks and encouraged its European partners to train Ukrainian soldiers in their use.

In May 2023, Ukraine officially requested the delivery of Taurus long-range missiles. However, as early as June 2023, Olaf Scholz and Defense Minister Boris Pistorius indicated that Germany would not supply these missiles. This position was reaffirmed in January and February 2024 by the Chancellor, who maintained his refusal while approving the delivery of other long-range weapons. While this decision was supported by public opinion in favour of military aid, but more reluctant to send Taurus missiles, several political parties, including the CDU/CSU Union, the Greens and the FDP, argued in favour of sending them to Ukraine.

At the same time, the government’s lack of clarity on the purpose of its aid to Ukraine, notably its refusal to deliver the Taurus missiles and the absence of an explicit commitment to a Ukrainian victory, has generated tensions with its partners. Similarly, while energy diversification has been achieved with remarkable speed, it has been accompanied by new dependencies, notably on Qatar and Azerbaijan, while the pursuit of close economic relations with China raises concerns about Germany’s strategic resilience.

Moreover, Germany’s inability to effectively mobilize the €100 billion special defence fund is a clear illustration of the bureaucratic blockages, budgetary constraints and political tensions that are hampering its ability to respond to the strategic imperatives posed by the war in Ukraine. Despite the Zeitenwende announcement, implementation of these funds remains slow and inadequate, with key military equipment – including F-35 fighters, helicopters and tanks – not expected for several years.

What’s more, a significant proportion of these resources has been earmarked for acquisitions already planned before 2022, limiting their impact on the immediate transformation of Bundeswehr capabilities, whose operational readiness has not improved significantly. In addition, inflation and the cost of financing the fund have reduced its real value, while the defense budget remains insufficient to guarantee a sustainable rearmament effort after it runs out in 2027.

These difficulties are compounded by a lack of consensus within the government coalition, which has led to a halving of planned military aid to Ukraine and increased reliance on uncertain funding from European funds or frozen Russian assets. In the absence of a clear strategy and reformed procurement processes, Germany appears insufficiently prepared to assume its NATO commitments and play the role of military power that Chancellor Scholz had promised to embody.

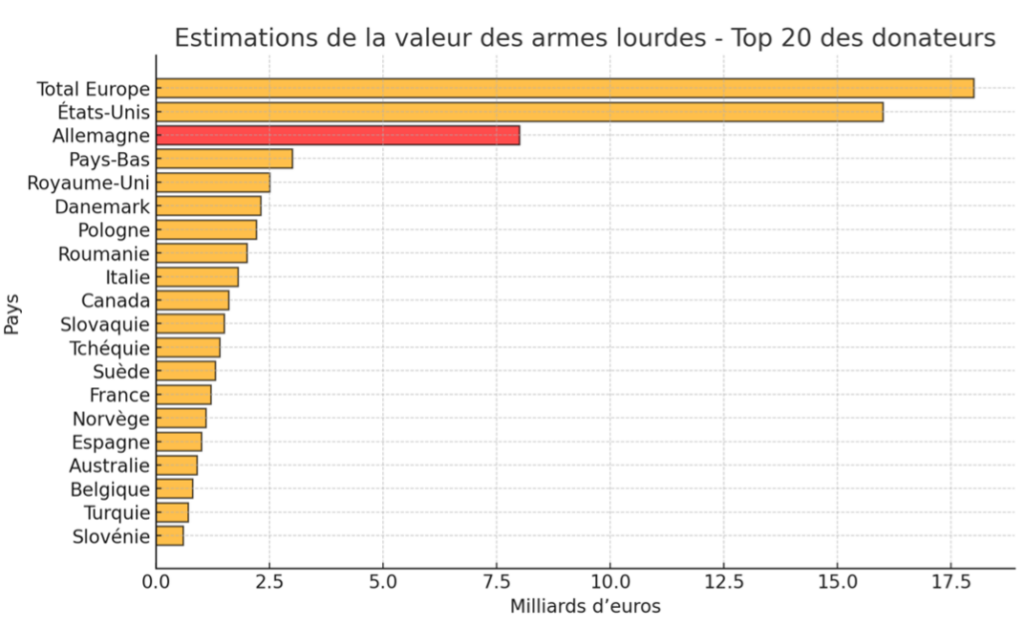

Despite this, Germany remains an important player in military support for Ukraine. It is one of the leading suppliers of heavy equipment, second only to the United States. Its commitment includes the delivery of 175 infantry fighting vehicles (155 already delivered), 60 tanks (52 delivered), 92 howitzers (34 delivered), 27 anti-aircraft missile systems (14 delivered) and 8 multiple rocket launchers (all delivered).

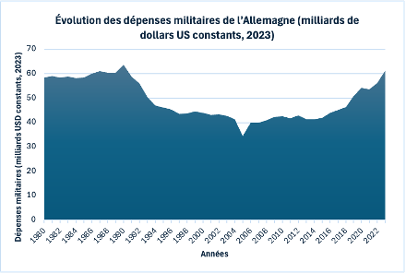

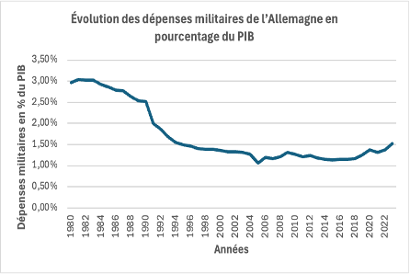

Thanks to the €100 billion special fund announced at the start of the war, Germany has recently reached 2.12% of its GDP in defence spending, joining other NATO member states that have gradually increased their military budgets since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, and then more markedly after 2022. Indeed, thanks to the special fund, Germany has announced spending 90.6 billion euros on defence in 2024 (budget of 51.9 billion euros + special fund). However, this special fund is expected to be exhausted by 2027. To maintain a spending level of 2% of GDP, Germany would need to allocate an additional €20-30 billion annually. Some experts and politicians argue for a more substantial increase, estimating that a defence budget equivalent to 3 to 3.5% of GDP-or around €120 billion a year-would be necessary. However, the share of the budget earmarked for defence in 2025 would amount to 53.25 billion euros, representing a modest increase of 1.2 billion compared to 2024.

Against a backdrop of budgetary constraints imposed by the 2009 Debt Ceiling Law, Berlin will have to identify solutions to guarantee sustained financing of its defence effort over the long term. Chancellor Olaf Scholz is opposed to further increases in the budget for 2025, while the head of the CDU/CSU union rejects the idea of financing these increases through increased recourse to debt. Some experts put Germany’s cumulative underinvestment in defense at around 600 billion euros. According to the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Armed Forces, at least 300 billion euros would be needed to ensure full operational readiness.

Early federal election in February 2025

Gradually weakened over the course of 2022, the Tricolour coalition has seen its support erode, being gradually overtaken in the polls by the conservative CDU/CSU union and by the surging AfD. While international issues did not cause the Scholz government to collapse, James Bindenagel and Karsten Jung point out in an analysis for the German Marshall Fund that the upcoming federal election on February 23 will determine how seriously Germany takes its response to the historic turning point brought about by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Two structuring elements of the German elections are important to understand. Firstly, the mixed representation mode of the German electoral system usually imposes the formation of coalitions, with the CDU/CSU and SPD historically dominating these alliances with smaller parties such as the FDP or the Greens. On the other hand, the political exclusion of the AfD remains a major dividing line. A cordon sanitaire (Brandmauer) has so far prevented any coalition with the extreme right, despite its electoral progression. However, a recent joint vote between the CDU/CSU and the AfD in the Bundestag represents a historic break, marking the first form of parliamentary cooperation since the Second World War.

The CDU/CSU, SPD, FDP and Greens agree on the need for continued aid to Ukraine, but differ on the extent of this aid. The SPD defends Scholz’s cautious line, arguing that Germany should support Kyiv for as long as necessary without risking an escalation with Moscow. Scholz is trying to position himself as the guarantor of peace, emphasizing his ability to avoid a widening of the conflict, particularly in the face of CDU leader Friedrich Merz.

The CDU/CSU, however, criticizes this cautious stance and calls for increased military assistance, including the delivery of Taurus missiles. The FDP and the Greens also support an increase in military support, emphasizing the reconstruction of Ukraine and the strengthening of its infrastructure.

Conversely, the AfD criticizes under-investment in the armed forces, but opposes arms deliveries, arguing for a foreign policy focused on German national interests. The AfD also calls for eventual neutrality on the part of Ukraine. Die Linke, while critical of Russia, also rejects arms shipments and advocates a diplomatic solution to the conflict, favouring targeted sanctions against those close to the Kremlin over a generalized economic embargo. Like the AfD, the new left-wing populist party Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW) blames NATO and the USA for the conflict, and rejects any military aid to Ukraine.

In view of the challenges posed by the war in Ukraine, the CDU/CSU, SPD, FDP and Greens support an increase in the defence budget. The SPD is committed to maintaining a budget of at least 2% of GDP, considering this effort to be central to European security. The CDU/CSU insists on the need for greater commitment and calls for rapid modernization of the armed forces. The FDP, for its part, stresses the need for a fully operational Bundeswehr, adapted to new threats.

The Greens, historically pacifists, now advocate a sustainable strengthening of military capabilities. Annalena Baerbock believes that Germany should invest more than 2% of its GDP in defence on a stable basis, while Robert Habeck, the Greens’ candidate for chancellor, calls for this contribution to be increased to 3.5%.

The AfD supports the improvement of military capabilities, but rejects any European integration of defence, advocating a strictly national approach and the reinstatement of compulsory military service. Die Linke, on the other hand, advocates a reduction in military spending and an end to Germany’s NATO commitments.

The Russo-Ukrainian war has profoundly redefined the debate on foreign and defence policy in Germany. While there is still a majority consensus in favour of supporting Kyiv, tensions persist over the scale of aid and future strategic choices.

The future of German engagement in Ukraine

In light of the polls, no political party seems likely to secure an absolute majority, opening the way for various coalition configurations. A ‘grand coalition’ (Große Koalition, or GroKo) between the CDU/CSU and the SPD remains a possibility, although this alliance has been marked by tensions in the past. A black-green coalition, bringing together the CDU/CSU and the Greens, also appears possible, as these parties share common ground on economic governance and environmental policies, although divergences remain on social and security issues. A Jamaica coalition, composed of the CDU/CSU, the Greens and the FDP, remains another option, its name being taken from the parties’ colours, which correspond to those of the Jamaican flag.

Given the CDU/CSU’s clear lead in voting intentions, a left-leaning coalition including Die Linke seems unlikely, especially since the conservative union has ruled out any alliance with this party. Similarly, a collaboration with the AfD is excluded due to the cordon sanitaire applied by all democratic parties, which refuse any cooperation with the extreme right. Consequently, post-election negotiations should mainly focus on the balances between the CDU/CSU, the SPD, the Greens and the FDP. Thus, no government should include the three parties most critical of support for Ukraine, although they represent a growing share of public opinion.

Three coalition scenarios are emerging, each with implications for German defence and support policy for Ukraine. A CDU/CSU-SPD coalition would continue military aid to Kyiv, as both parties share a historic commitment to NATO, a cornerstone of German security since the FRG joined the Atlantic Alliance in 1955. The CDU/CSU has always advocated a strong commitment to the Alliance, considering the transatlantic anchorage as essential to European security. The SPD, although more nuanced, has also contributed to the consolidation of Germany’s role in NATO, notably by supporting the enlargement of the Alliance and supporting the transformation of its missions towards crisis management. However, differences persist over the extent of military support for Ukraine: while the CDU/CSU union advocates increased assistance, the SPD, committed to a more cautious approach, could moderate certain decisions, notably regarding the delivery of Taurus missiles, in order to avoid any escalation.

A CDU/CSU-Green coalition would favour increased military engagement with Ukraine and increased defence spending. Robert Habeck and Friedrich Merz, respectively leaders of the Greens and the CDU/CSU, have both lobbied the Scholz government to authorize the delivery of Taurus missiles to Ukraine. Such a coalition would mark a major shift in German defence policy, placing Berlin in a more assertive position vis-à-vis Moscow. However, tensions could emerge over budgetary and fiscal issues, making the government balance fragile.

A third option would be a renewal of the traffic light coalition (SPD-Greens-FDP), which would maintain limited support for Ukraine, but would remain marked by internal blockages, notably on the financing of military aid and the qualitative increase in arms deliveries, perceived as a risk factor for escalation.

Regardless of the government that emerges from the elections, the growing influence of the AfD and BSW could change parliamentary dynamics. The latter, a new populist party, opposes military aid to Ukraine, could cross the 5% electoral threshold and gain seats in the Bundestag. A rise in the AfD and BSW would put additional pressure on a drastic reduction in military aid, or even an opening to negotiations with Moscow. Although they are unlikely to participate in a government, their presence in the Bundestag could influence the strategic debate.

The announcement on February 17th of possible negotiations between Russia and the United States without Ukraine’s participation sparked strong reactions in Europe. In response, French President Emmanuel Macron brought together several European leaders to coordinate a common position on this US initiative. The main traditional parties in Germany (with the exception of the AfD, Die Linke and BSW) strongly criticized this approach as unacceptable. After the meeting, Chancellor Olaf Scholz reaffirmed his support for Ukraine and European military aid mechanisms, while postponing any discussion of a possible deployment of peacekeeping forces until a structured peace plan is adopted.

The return of Donald Trump to the White House introduces major uncertainty regarding US support for Ukraine, which could force Europe, and Germany in particular, to assume greater responsibility for military aid. If Washington cuts its assistance, Berlin will have to make a crucial choice: to compensate for this shortfall by increasing its commitment or to encourage a negotiated settlement of the conflict. However, budgetary constraints, growing voter fatigue, and the domestic political context make any leadership in aid to Ukraine particularly delicate, both financially and politically.

The future of German support for Ukraine will therefore depend on the outcome of the elections and the coalition that emerges. Scholz and the SPD will probably continue to favour a moderate approach, while the CDU/CSU and the Greens will argue for increased military engagement. At the same time, the rise of the AfD and BSW could fuel pressure for a reduction in arms deliveries and an opening to negotiations with Russia.

Comments are closed.